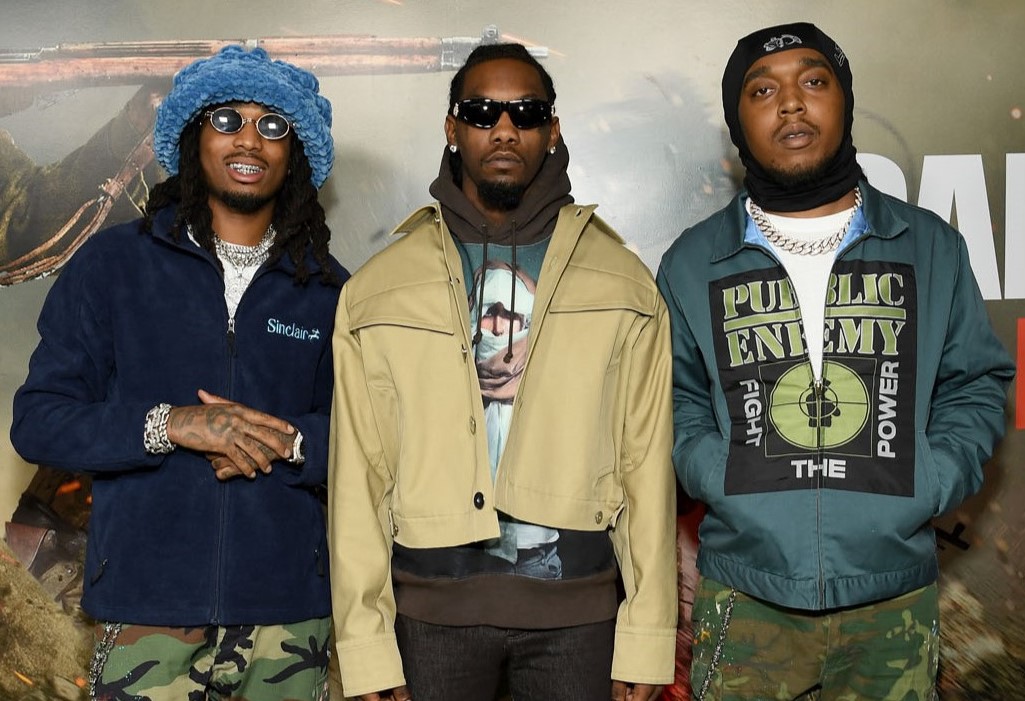

Quavo, Offset, and "complicated grief"

Over the last few days, Quavo and Offset have both shared emotional statements about the death of Takeoff. Taking to Instagram to express their sentiments, the two reflected on what he means to them, and how difficult it has been to find a way forward after he was shot and killed on November 1.

“This whole time I’ve been trying to figure what you really are to me because nephew wasn’t it…we always knew we were way closer than that and it made me feel old too. But I knew you weren’t my brother cuz you are my sister’s son, so I couldn’t say brother. Now I finally get it…you are OUR angel,” Quavo wrote over the weekend.

And last night, Offset posted a shorter, but equally emotional statement, followed by images and videos of the three of them together.

“The pain you left me with is unbearable. My heart is shattered and I have so many things to say, but I can’t find the words...I know someone with a soul like yours is in heaven now. I hope you can see how much we love you and miss you.”

Earlier this year, Migos became a duo with just Quavo and Takeoff, and Offset struck out on his own. Quavo appeared on the Big Facts podcast in October, just before Takeoff’s death, suggesting the group was experiencing a family issue that had nothing to do with business or music, but insisted they’d always be family.

“Family always going to be family. We always family. Ain’t nothing gonna change,” he said.

Being estranged from anyone ahead of their death is an impossibly difficult situation to navigate – and I can only imagine how it has complicated this loss for him, and perhaps left him with a feeling of inescapable regret. But it’s encouraging to see Quavo and Offset release statements that not only show a side of Takeoff the general public may not have known existed, but a side of them that we don’t often see. The pain, the sorrow, and sense of loss are all signs of immense grief, and it’s important that they feel safe enough to express their emotions.

But why wouldn’t they feel safe enough to express their grief? It’s a fair question with a nuanced answer. All grief is difficult and complex. But grief in Black communities is even more layered and has its own historical roots. This is not to say Black grief matters more than others, the point is simply to acknowledge the historical context surrounding it and to call attention to the disparities in how often Black people experience grief and the absence of the privilege required to truly sit in bereavement.

Earlier this year, a study looked at Black grief, suggesting that the current conceptualization of it as being “the acute pain that accompanies the loss of a loved one” to be too narrow in scope. The study authors suggested society’s current idea of grief is not accounting for the various ways it’s manifested among Black people – and how the history of being racialized has made grief an especially unique experience of loss and bereavement.

The study differentiates personal loss and collective loss, saying that many of the deaths Black people experience are not necessarily the deaths of our friends and immediate family members. But people like George Floyd, who could have been our brother, or women like Sandra Bland and Breonna Taylor, who could have been our sisters.

"Personal loss is a domain where the loss is more of an individual experience, like losing a loved one, whereas collective loss is more of an experience that happens communally," said Da’Mere Wilson, a doctoral student in psychology.

Consider how connected the world felt to George Floyd, who most of us didn’t know personally. Imagine the pain we feel when we lose someone like Takeoff, a treasured and valued star in our community, who many of us watched grow and evolve over the years. He could have been our cousin or our brother. We relate to him, we see so much of ourselves in him, so the loss is incredibly personal. Now consider the death of Chadwick Boseman, a man who was so revered, not only by Black people, but by a worldwide audience. He brought us one of the greatest Black heroes of all time in Black Panther.

I remember when it premiered in 2018. Black Twitter was set ablaze with conversations of what we would be wearing to watch it. It was the first time we saw a predominantly Black cast in a Marvel movie – and it was the franchise’s first film about a Black superhero, with a Black man as the lead. For so many, it was the first time we heard African names and saw African clothing on the big screen.

It was a celebration of Black art. And it shattered the idea that there was no return on investment in big budget Black films. It earned more than a billion dollars worldwide, becoming the first Marvel movie to be nominated for Best Picture at the Oscars. And those costumes? They snagged a golden trophy, along with awards for Best Original Score and Production Design. Losing such an iconic figure as Chadwick Boseman to cancer was painful.

As loss and grief takes centre stage in Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, I can’t help but wonder whether it’s triggering or healing for people going to watch it – or perhaps a bit of both. Anyone walking into a theatre to see it is aware that yes, they’re going to watch a movie, but in a way, they’re also going to experience and observe loss and grief in some capacity. And after all the loss that we’ve suffered over the last two years, it can be cathartic.

It’s important that Black people are relieved from the pressure to be stoic, the pressure to be strong in moments of weakness, sorrow and grief. We should be able to take the time that we need for ourselves and for our souls to sit with the complex emotions that come from loss – whether that loss is a personal one or a communal one. And we have to keep the conversation going.

“We must expand our definition of grief to account for the pain that occurs within the Black community after the loss of a loved one, the loss of land, the loss of a sense of safety, and the loss of members of the community due to direct and indirect acts of racist violence,” the study suggests.

It’s why the study also encourages the expansion of the research to help further the understanding of grief in communities with similar experiences, like Indigenous peoples who have also suffered tremendous losses of land, identity, history, culture, language and traditions.

There have been a handful of studies that focus exclusively on Black loss, but most focus on homicide-related loss, which Takeoff’s death is categorized as. Statistically, Black people are more likely to experience the murder of a loved one, but with such a narrow scope of focus, there isn’t much research available for the many other types of losses we experience, like illness or suicide – also things that disproportionately affect Black and Indigenous people.

“Those who experience traumatic bereavement typically experience more intense and severe grief and trauma related symptomology when compared to those who experience a natural death of a loved one,” the study suggests, before pointing to increased rates of PTSD in Black people who have been affected by homicide. It’s referred to as “complicated grief”, and a lack of access to psychosocial services can exacerbate the symptoms and experience of it.

Obviously for Offset and Quavo, affording therapy won’t be an issue. But being able to pay for it doesn’t mean they’ll go, especially if they, like so many other racialized people, see being in a place of needing therapy as a weakness. It’s my hope that Quavo and Offset experience the deepest form of healing there is and are helped by those who understand and validate the trauma of what they’ve experienced, not only in the last month but over the course of their lifetime as Black men in America who have likely witnessed a lot of sadness and strife. I hope that where there is anger, strife and grief, there will instead be peace, love and resolution. But most importantly, I hope that this moment serves as an opportunity for Black people to be granted the room and freedom to process so many of the personal and communal losses we’ve endured.