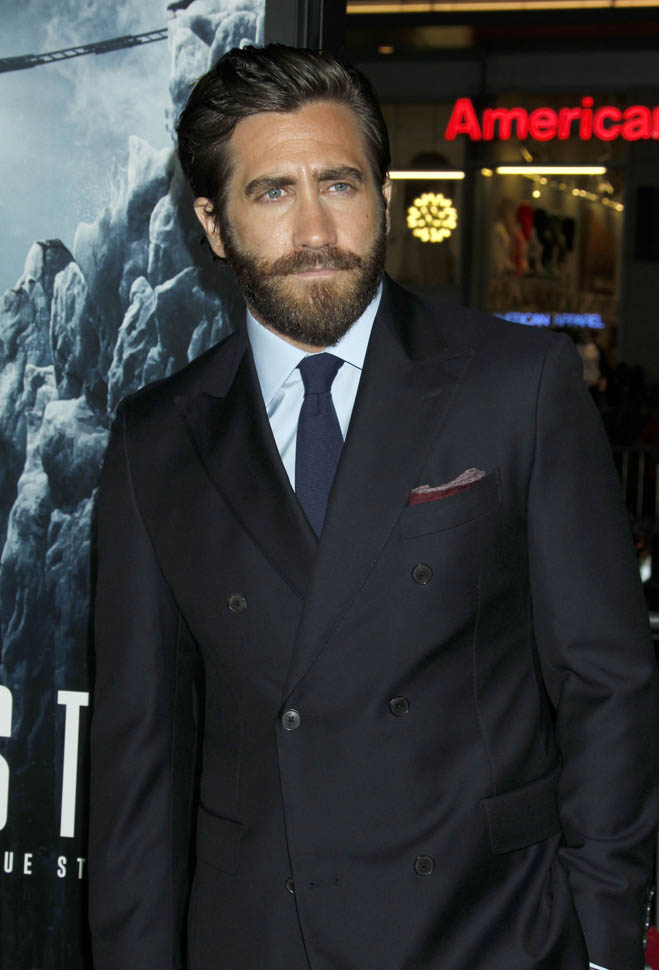

Jake G in Everest

Actually, I should say that it’s Jason Clarke in Everest because Jake Gyllenhaal has a relatively small role and disappears from the film for long stretches, but he’s being treated in the publicity materials like he’s the star, and I don’t know how many of you are really here for Jason Clarke, while I know there are a bunch of us scanning for Jake G. So Everest is the “Jake Gyllenhaal mountain movie” while also being the “movie Jake Gyllenhaal isn’t in that much despite the trailers and everything else making it appear otherwise”.

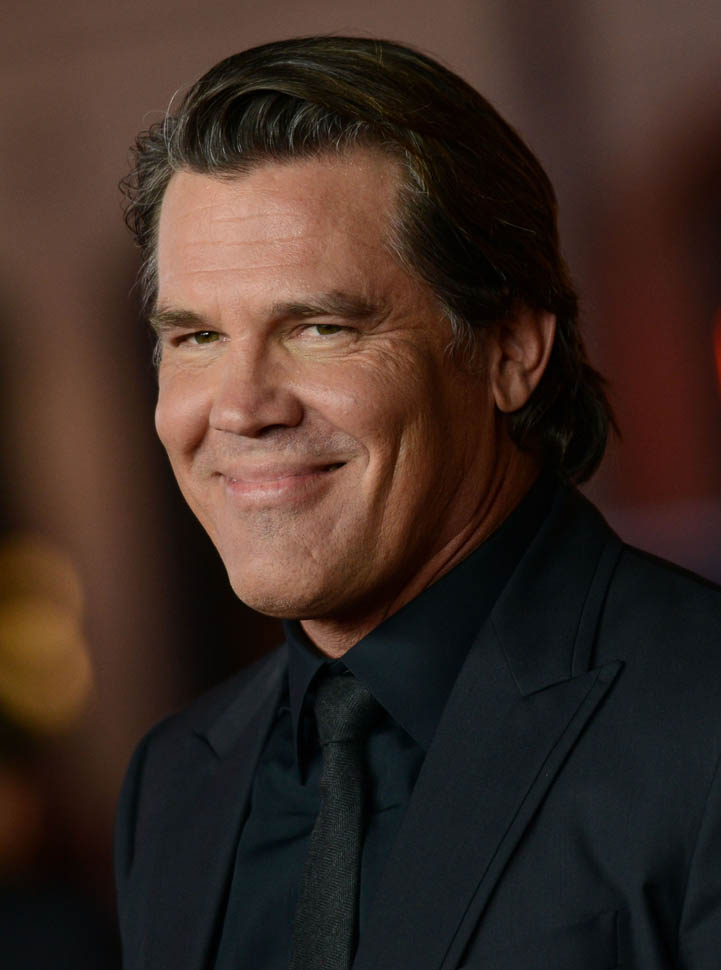

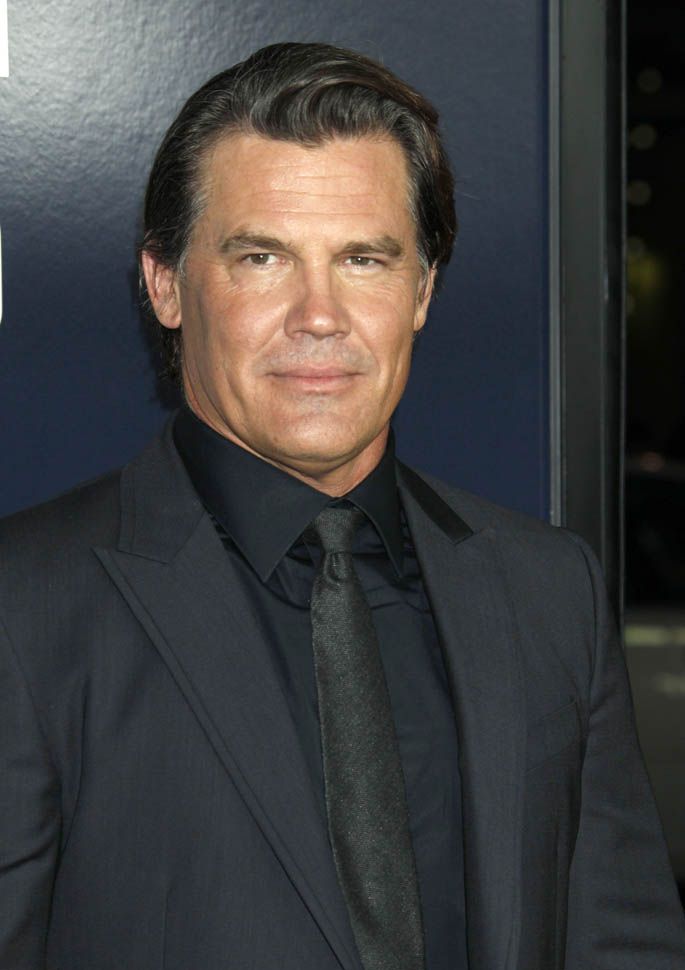

Everest, directed by Icelandic filmmaker Baltasar Kormakur (Contraband, 2 Guns, and the stellar Icelandic survival film The Deep), recounts the 1996 climbing disaster on Mount Everest that killed eight mountaineers in one day, one of the worst disasters on that mountain. Per the film’s publicity department, Everest is totally not based on Jon Krakauer’s book, Into Thin Air, even though they use his version of events and basic characterizations of the people involved. If you’ve read Into Thin Air, Everest will feel familiar. We’re introduced to the main players of the Adventure Consultants team, led by Rob Hall (Clarke), as they gather in Kathmandu before setting out for Everest’s base camp. Once there, they meet Scott Fischer (Jake G), leader of the rival Mountain Madness climbing outfit.

The script by William Nicholson and Simon Beaufoy does an acceptable job balancing the plot between the climbers, the people coordinating rescue efforts back at base camp, and the families left behind, and Mick Audsley’s editing hangs together well, though it gets hard to keep track of characters because there are a lot of them and their faces are covered by oxygen masks for much of the second half. Plus not many of them are actually memorable—the emphasis is not on the people but on the event. The pressure of commercial climbing is the real “bad guy” of the film, which opens up Kormakur’s angle, which is what makes Everest interesting—the mountain is not the villain.

Usually in Man vs. Nature stories, Nature is the villain. It’s out to get us—it’s a monster, a beast, a malevolent force of will punishing us for some wrong we’ve committed. It’s not hard to understand why we anthropomorphize Nature, but it isn’t really cruel or cold or murderous, it just is, and there are vast swaths of Nature outside Man’s domain (which we, as a species, simply cannot tolerate). The closest Everest comes to anthropomorphizing the mountain is the statement, “The competition is between us and the mountain.” But there is no competition. There is only the mountain, Nature’s indifference, and Man’s need to conquer something incapable of noticing us. Kormakur, taking a very Werner Herzog approach, shows that Man never really stands a chance.

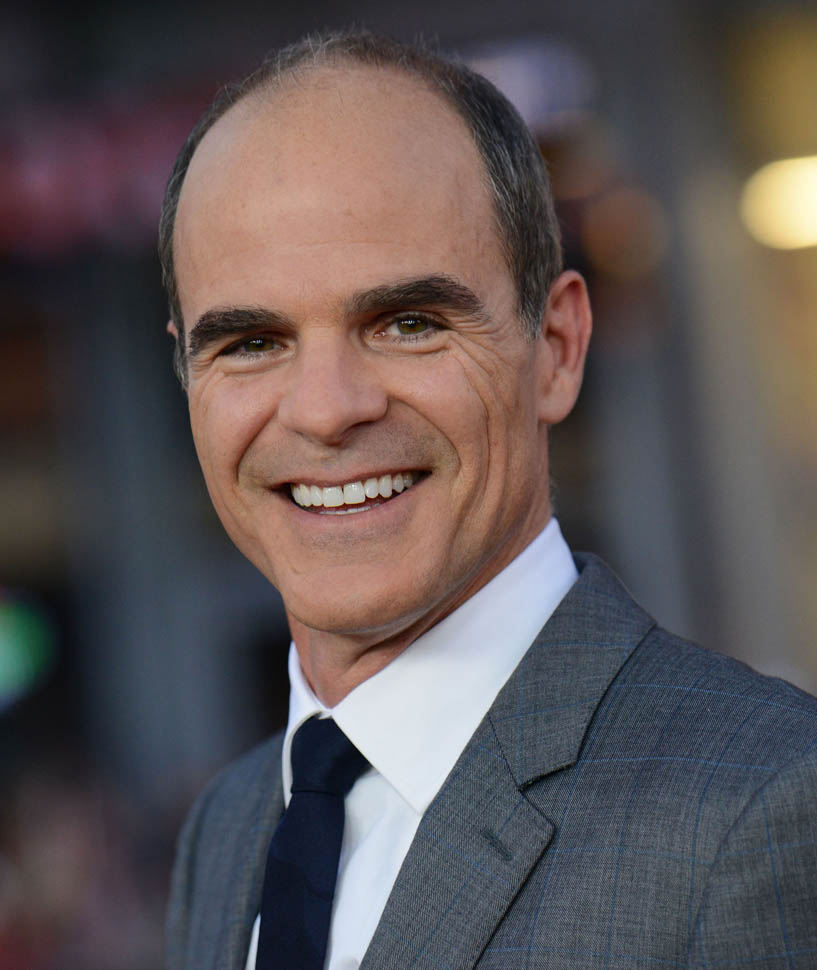

Things go wrong immediately—overcrowding is prevalent, Scott Fischer is clearly not well, Rob Hall is under pressure to not only satisfy his paying clients but also make it look good for travel writer Jon Krakauer (Michael Kelly), who is along for the ride. The reasons these people are driven to climb Everest are kept vague, basically amounting to, “Because it’s there and we can,” though Doug Hansen (John Hawkes) talks about inspiring kids to follow dreams. Everest doesn’t invest much in character, which also means it doesn’t aggrandize any of the players involved, except perhaps Hall, who found a way to make a living off his passion and quickly lost the ability to control the variables.

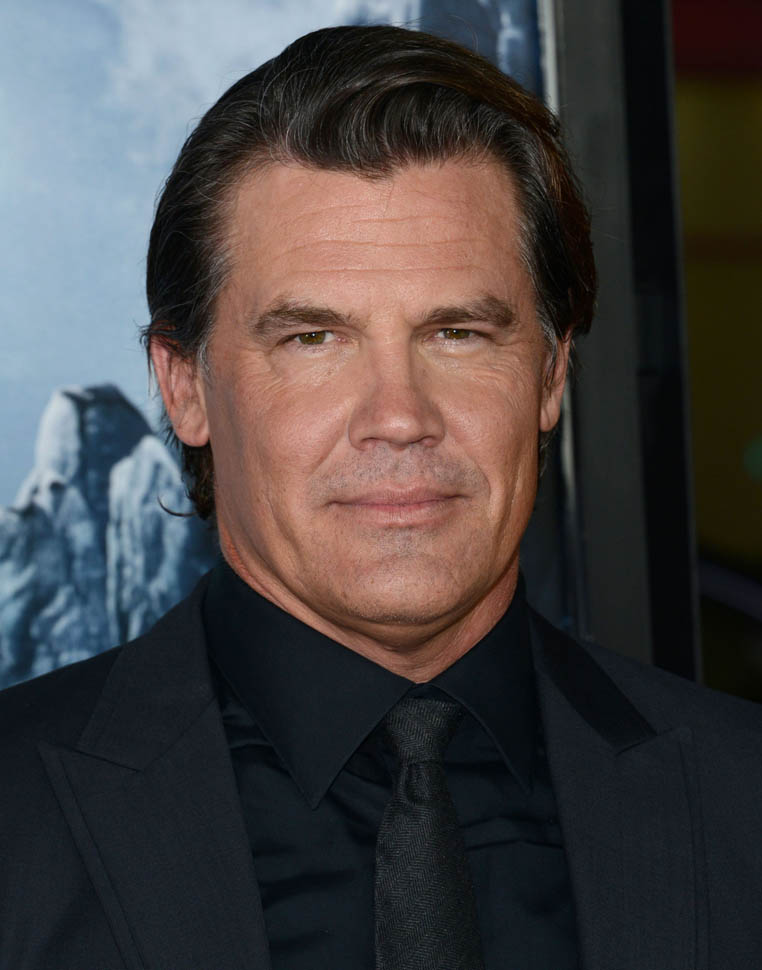

And then they’re on the mountain, and, well, Nature happens. Beck Weathers (Josh Brolin) can’t see well enough to complete the summit, and spends most of May 10 sitting in one place in the snow, waiting for a guide to help him back down, which couldn’t have helped his circulation. Hansen struggles to keep up, potentially endangering himself and others. A late start on the descent puts the combined Adventure Consultants/Mountain Madness team on the south summit of Everest when the blizzard hits, stranding them overnight. Some, like Krakauer, make it Camp IV and the relative shelter of a pup tent. Others, like Weathers, Hall, Hansen, and Japanese climber Yasuko Namba (Naoko Mori), spend the night totally exposed.

There aren’t many beauty shots of Everest in this movie. If you’re looking for sweeping vistas and grand visuals, you’re in the wrong place. Instead, Kormakur and cinematographer Salvatore Totino (a frequent Ron Howard collaborator) focus on jagged cuts of glacial ice, deep crevasses, and the sheer, seemingly impossible passes these people must cross in order to summit the mountain. Death is unremarkable and inevitable, and survivors are not treated as heroes. Everest is not a triumphant story of human courage and sacrifice. It’s a reminder—we are powerless in the face of Nature’s indifference.

Everest is currently in limited/IMAX release and opens wide today.