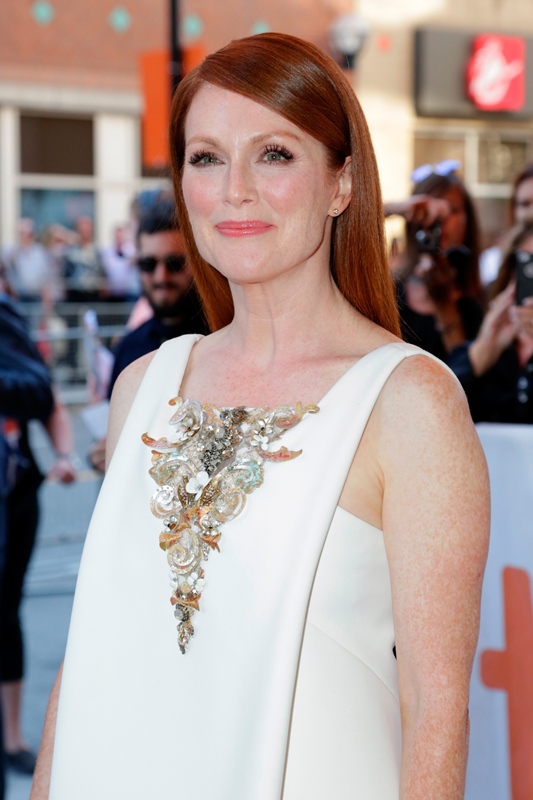

Julianne Moore in Still Alice: TIFF review

Julianne Moore’s unrelenting commitment to her characters and epic crying face merits a thousand viral video super-cuts. Critically appreciated, but woefully under-awarded, 2014 could be the year she receives her fifth (or sixth) Oscar nomination with her prodigious turns in both Still Alice, and Maps to the Stars.

But, as Maps gears up for a 2015 release, her electrifying, and polarizing portrayal of a desperate falling star will remain unseen by many – for now. Her chances now lie with Still Alice, where Moore plays a linguistics professor who suffers from early on-set Alzheimer’s, and is reluctantly tended to by her husband John (Alec Baldwin) and youngest daughter Lydia (Kristen Stewart).

“Hollywood Alzheimer’s” has become a played-out cliché of extreme anger and sentimental gloom, ranging from Richard Jenkins’ turn as Justin Timberlake’s wistful father in the subpar Friends with Benefits, to that very special episode of Full House. However, with Still Alice, we see the frustration and mental decay from the patient’s viewpoint, as Moore’s Alice begins to forget the very words she used to build her career and reputation at Columbia University. Instead of bigging up the symptoms and alienation of her loved ones, her intellectual capacity and recognition slowly falls out of her grasp. It’s only when she loses her sense of direction while out on a jog that she realizes she, at 50, might be more than absent-minded, and none are more surprised than John.

Immediately, she rushes to her own defence, leaving clues and sleeping pills around the house, recording videos on her laptop with hints and tricks, and forcing her eldest daughter Anna (Kate Bosworth) to play as many games of Words with Friends with her as possible. She’s desperate to regain her facilities, and refuses to lose her strength, rarely bursting into the tears that have become Moore’s trademark. But we quickly see Alice’s short-term memory decline and disorientation is coming, fast and furious. Soon, answering her own memory quizzes on her iPhone and remembering timelines becomes a struggle, as do tasks like getting dressed, or using the bathroom. She pleads with her husband to take time off from his medical career to spend a year together as husband and wife while she can create new memories, but he rejects her appeal, instead aiming to advance his own ambition.

As the ambitious Alice, the fire in Moore’s eyes dims as she begins to misidentify or forget her three children, or the layout of her own home. This cognitive descent is played up further when she delivers prepared remarks at an Alzheimer’s conference, often repeating words, and bringing the audience to tears. When she drops her papers, she says she hopes he will forget that moment, and insists that she soon will. The subtlety of this flickering recall is reminiscent of Moore’s acting in the fiercely quiet and powerful Far From Heaven. She’s firmly in control, and though Baldwin is playing an amalgam of his “Smart Alec” persona as best as he can, this film becomes a master class showcase of Moore’s creative restraint.

Directed by Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland, the film’s brazen focus on Alice’s anxiety and prevention of mental defeat is a result of their partnership, and personal adaptation of the 2007 novel. According to the Hollywood Reporter, Glatzer, who has ALS, co-directed the film using an iPad and text-to-speech app. The result of their strong partnership? A quiet, understated movie to remember.