Me and Earl and the Dying Girl

Spoilers, but also like, the title

Like Whiplash before it, one film won both the Audience Award and the US Dramatic Grand Jury Prize at Sundance this year: Me and Earl and the Dying Girl. Whiplash went on to bag five Oscar nominations, winning three of them. I don’t know if Dying Girl will have the legs to carry it all the way to Oscar—it’s not as ferocious a movie as Whiplash, and it lacks a fiery, attention-getting performance—but it is certainly a very good movie, and it wouldn’t surprise me to see it pull an Adapted Screenplay nomination, if nothing else, telling the story of awkward high school student Greg’s senior year, in which he befriends a terminally ill classmate, struggles with his future, and falls out with his best friend.

Directed by Alfonso Gomez-Rejon and adapted by Jesse Andrews from his own novel, Dying Girl is straight out of the Wes Anderson School of Twee Theatrical Filmmaking. Gomez-Rejon deploys a number of gimmicks from voice over narration, stop-motion animation representing inner thoughts, and twee as f*ck title cards that don’t all work equally well—the title cards, especially, are unnecessary. He’s also heavy-handed with his camera work, indulging in outright camera gymnastics, especially early in the film. However, there are an equal number of beautifully shot scenes, including one pivotal confrontation that is shot in one take from one angle that doesn’t even change focus, and that sustained perspective drives the emotional momentum of the scene as there is literally no escaping what is happening on screen. It’s an unrelenting, unrelieved view into a misery maelstrom that stands out as a superb moment in the film.

Greg is so precocious you want to punch him in the face, except that Thomas Mann’s performance is outstanding, especially in the final act. If Mann goes a little too hard on Greg’s awkwardness, he more than makes up for it when he digs into Greg’s grief. As senior year begins, Greg is neither popular nor unpopular, friendly with everyone but friends with no one, at least according to him. Greg is a bit Bella Swanny in the way that he insists he’s this horrible “groundhog-faced” geek, but everyone around him assures him that he is not, in fact, that terrible. It’s eye-roll inducing, but Mann is so winsome that he overcomes the writing and Greg comes off as painfully awkward instead of completely intolerable. He’s so emotionally repressed, though, that he refers to his one true friend, Earl, as his “co-worker” because they make movies together (one of the best parts of the film are the crappy knock-off movies Greg and Earl make, like Eyes Wide Butt, Grumpy Cul-de-Sacs, and A Sockwork Orange).

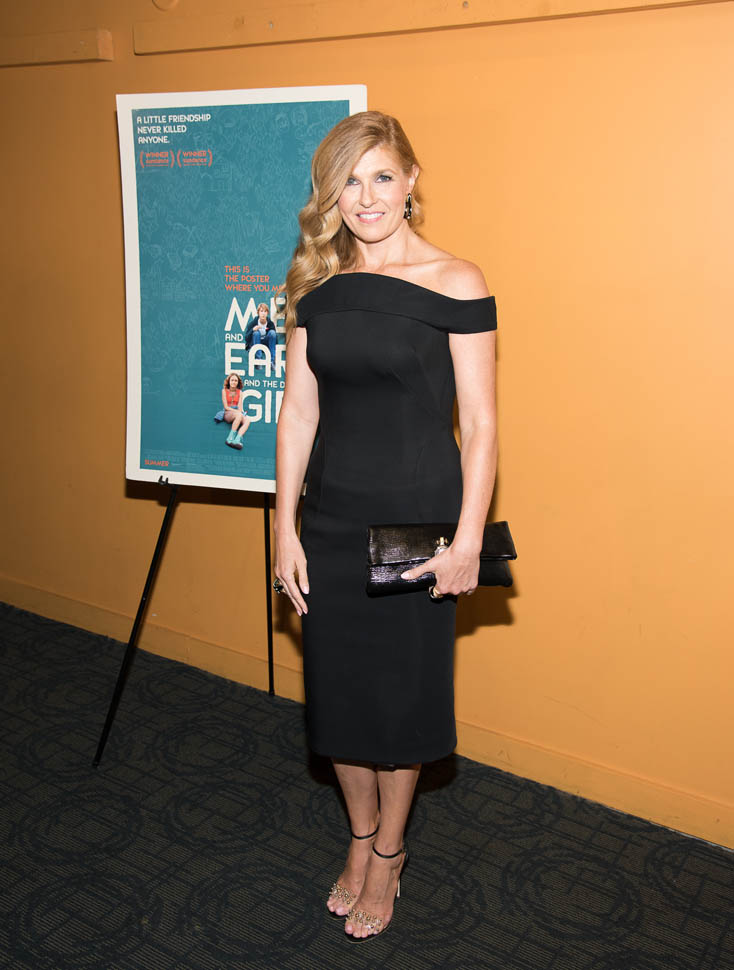

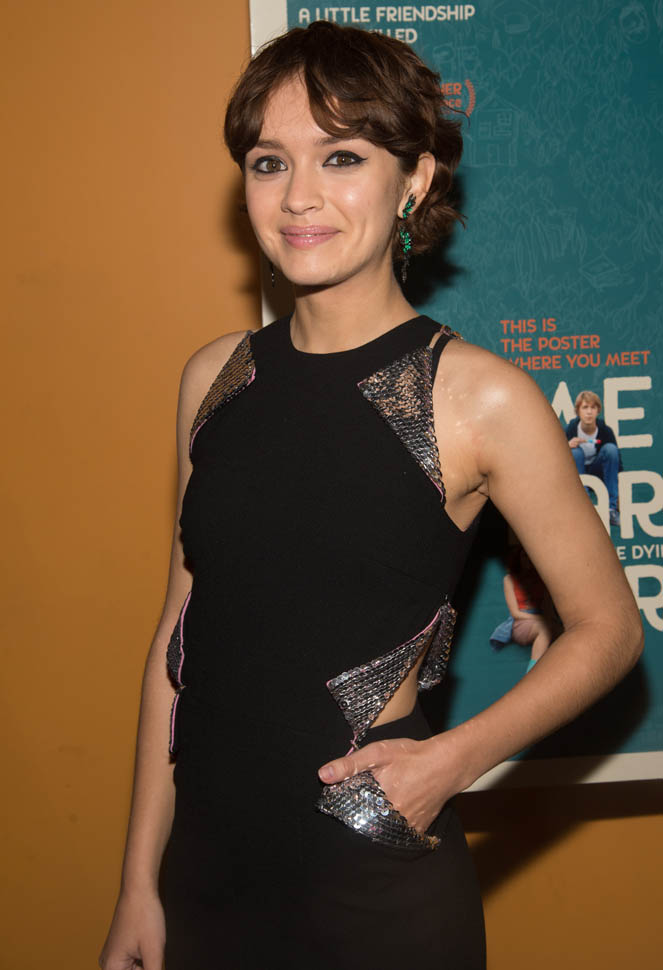

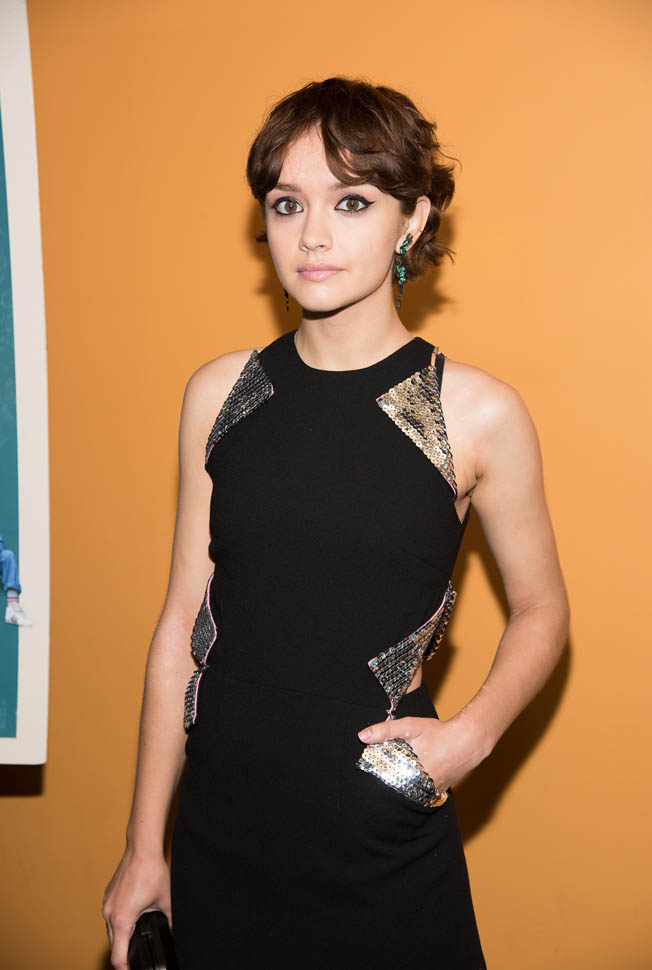

Upon learning that a classmate, Rachel (Olivia Cooke), has been diagnosed with leukemia, Greg’s mother—a delightfully daffy Connie Britton—forces him to spend time with the “dying girl”. The film takes place over the six months in which Rachel progressively gets worse, even as her friendship with Greg, and later Earl, grows deeper. We’re reminded a couple times that this is not a romantic love story between Greg and Rachel, and truly, what gives their relationship such weight is that they are just friends. When Greg brings Rachel a prom corsage, he isn’t fulfilling a romantic ideal, he’s including his friend in a rite of passage neither one thought they would participate in, and it’s a wonderful moment, unaffected by gimmicks and carried beautifully by Mann and Cooke. That’s also about when I started crying.

Me and Earl and the Dying Girl is annoying for the first twenty minutes, but stick with it. Once Gomez-Rejon’s aggressive direction settles down, the characters begin to really shine. It’s also completely heartbreaking for the last twenty minutes. Bring Kleenex—I am not a movie crier and I cried my eyes out through the entire third act. It sneaks up on you as the film balances the emotional weight of Rachel’s illness and Greg’s floundering attempts to support her with the more ridiculous aspects like Greg and Earl’s interpretive films and Greg’s hippy-dippy parents. Dying Girl has all the trappings of a twee nightmare, but it’s a deeply moving film.