American Animals is the reverse Ocean’s 8

There are two heist movies in theaters this month, Ocean’s 8 and American Animals. One is big and splashy, the other is a decidedly more low-key affair, and unlike Ocean’s 8, American Animals is based on a true story. It’s the stranger-than-fiction tale of how four college boys tried to steal a set of John James Audubon folios from a Kentucky college, and while I highly recommend American Animals in its own right, I especially recommend it as a companion piece to Ocean’s 8. You see, American Animals is about the intersection of cinematic fantasy, boredom, privilege, and what happens when you feel entitled to the excitement of the movies. It’s basically what would happen if you decided to plan and execute an Ocean’s-style heist of your very own. (Hint: You would get caught.)

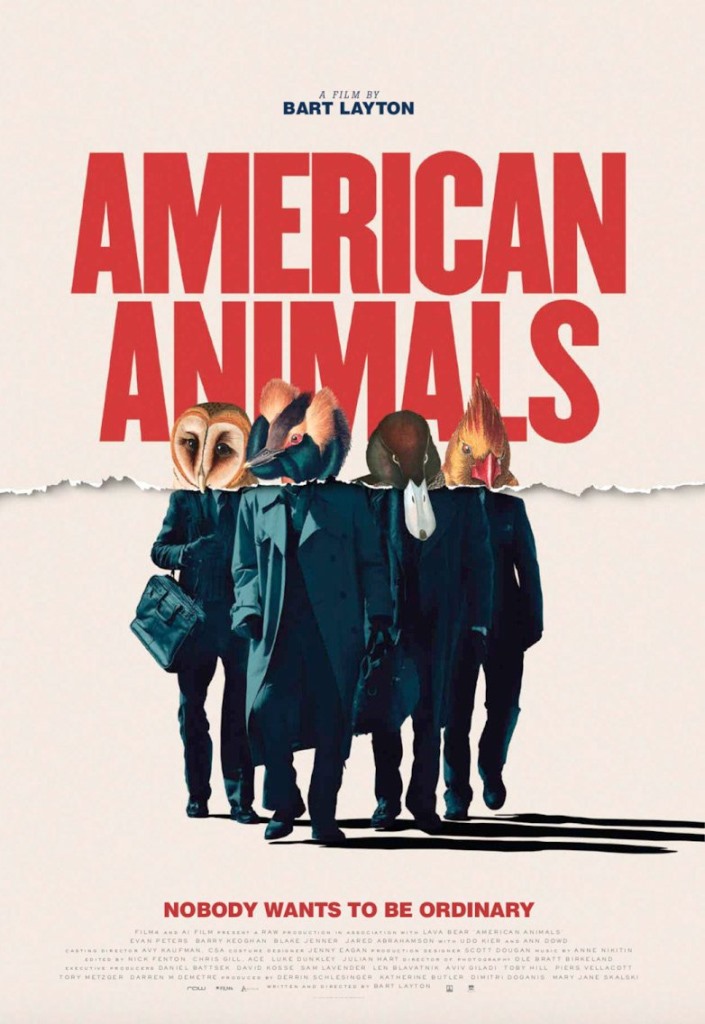

Directed by Bart Layton, the documentarian behind a similarly wacky tale, The Impostor, American Animals blends documentary and fiction in interesting and revealing ways. Cutting between narrative sections and traditional talking-head interviews with the four guys at the center of the heist—and their still-annoyed parents—Layton illustrates the unreliability of memory and provides context for the absolutely insane heist taking shape on screen. If you’ve ever watched a movie and wondered why a character would do a thing, then this is the movie for you, as Layton breaks out the interviews to tell you. And he does it without interrupting the pace or flow of the movie. The intercutting interviews are not distracting, and at key points they provide the grounding such an outlandish story requires (Richard Linklater’s Bernie works in a similar way).

The would-be art thieves are Warren (Evan Peters, who also did makeup on the movie), Spencer (Barry Keoghan), Chas (Blake Jenner), and Jared (Eric Borsuk). The trouble starts when Spencer is touring Transylvania University, a liberal arts college home to a special collection that includes a set of life-sized folios illustrated by John James Audubon. The librarian, Betty Jean Gooch (Ann Dowd), points out their worth, noting a recent sale in the mid-seven figures for a comparable set. Spencer mentions the folios to Warren, they form the dum-dum club, and a terrible plan is born.

They don’t really do it for greed. Of all the motives and post-hoc rationalizing provided in the film, greed is not a driving force. Instead, Layton examines the boys’ privilege—all are products of middle-to-upper-middle-class suburbia, and all are white—and their entitlement. They want their lives to be more, to be bigger, and they feel entitled to excitement, for their lives to be “more like the movies”. (This all happened in the early aughts, before social media, and one wonders if Instagram would have sufficed and saved them years in prison.)

It would be easy to dislike the four would-be thieves, but while the film doesn’t really solicit sympathy it is really hard not to get sucked into their cheerfully naïve planning. A couple of them are enthusiastic (notably Warren), with Chas the lone voice of reason constantly pointing out they’re going to get caught. They’re extremely foolish and they treat it like a game, their planning sessions just an excuse to hang out, until, suddenly Warren’s enthusiasm turns into real impetus. Suddenly, the heist is actually happening. It’s a disaster, of course, a comedy of errors from beginning to end, because life is not an Ocean’s movie, and art theft is not a hobby. The boys get caught and it plays with a feeling of satisfaction, like, yes of course these spoiled boneheads deserve to be punished for this.

But because the actual guys are on screen talking to you, it’s impossible to write them off as just spoiled boneheads. They did something monumentally stupid, but Layton explores their reasons in a way that highlights suburban ennui better than any film since The Ice Storm. It would be easy for American Animals to be a slapstick heist caper but Layton turns it into a meditation on middle-American torpor. It is an entertaining (failed) heist movie, but with Layton’s documentarian touch, American Animals is also an examination of the potentially dangerous entitlement of bored young men.