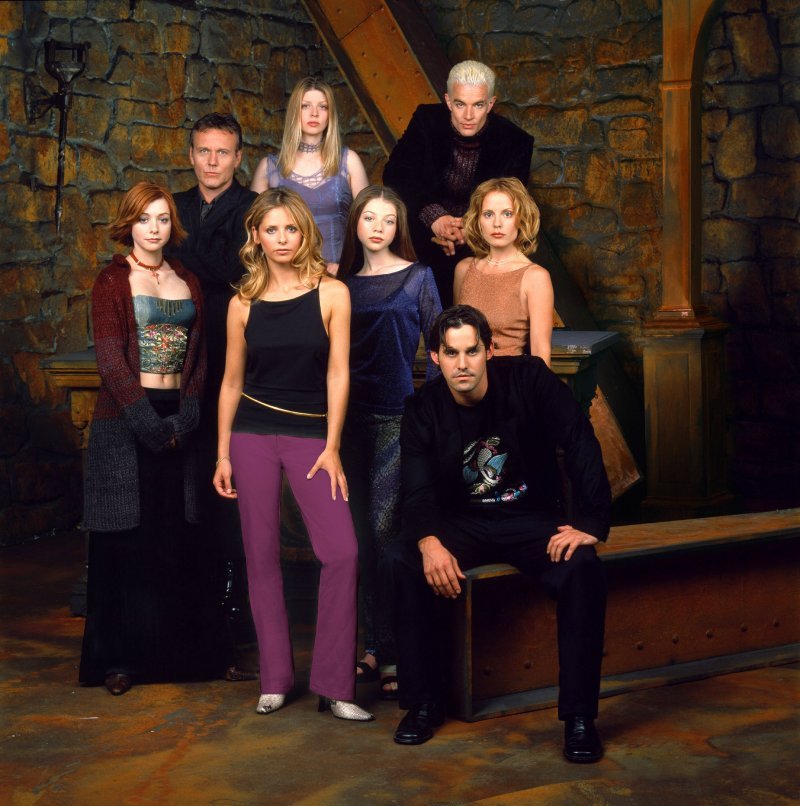

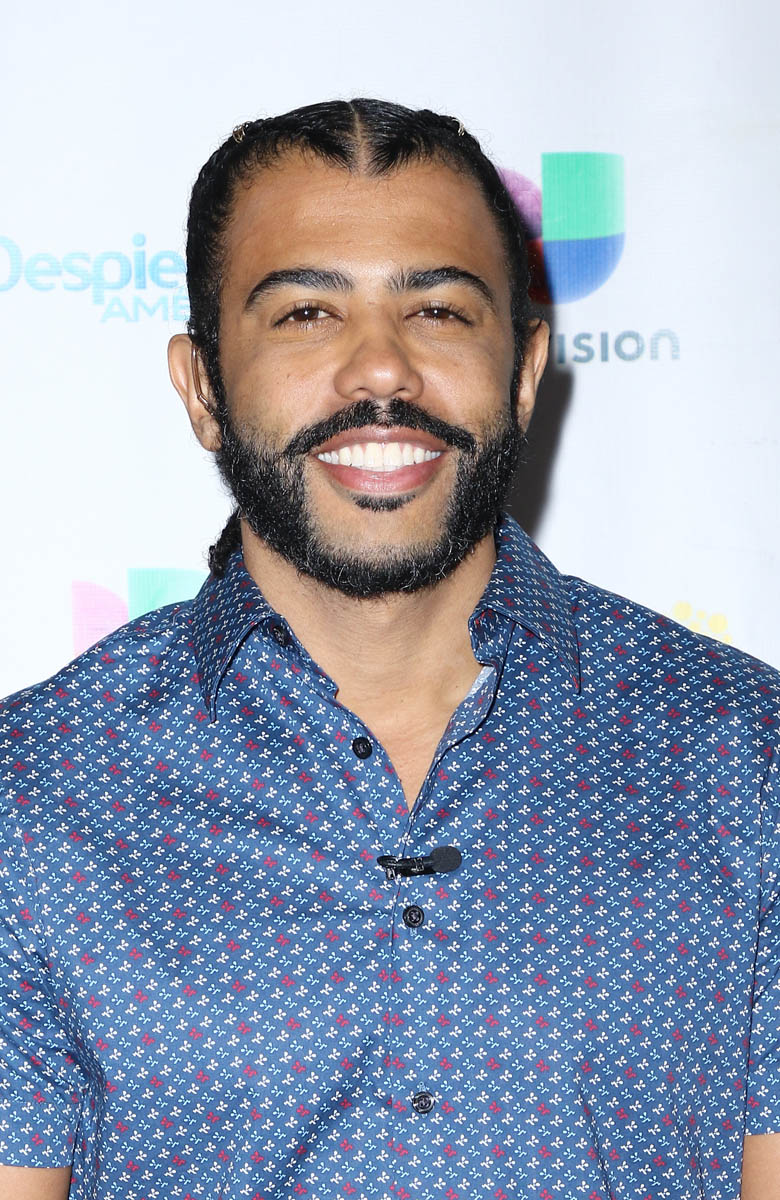

Daveed Diggs in Blindspotting

Daveed Diggs is the name you know, but Blindspotting is a work made with his creative partner Rafael Casal. They co-wrote, co-produced, and co-star in it, and it feels top to bottom like a collaboration—a story about two sides that requires two perspectives. Navigating between their voices is director Carlos Lopez Estrada who is, like Diggs and Casal, a first time features filmmaker. The freshman energy of Blindspotting propels it, and calls to mind another bold first time effort, Sorry to Bother You.

The two films have a lot in common—so much so, in fact, you wonder why Blindspotting’s distributor, Summit-Lionsgate, elected to open so close in the wake of Sorry, seeming not to realize how the similarities might cause an audience blind spot—and it’s impossible not to do a little comparing and contrasting, but just as over-identifying Sorry with Get Out misses the point of Sorry, conflating Sorry and Blindspotting ignores the different aims of each movie. Yes, both are set in Oakland, and both touch on race, class, and exploitation in America. But Sorry is explicitly concerned with the system itself, while Blindspotting delves more into the byproducts, specifically gentrification and privilege.

Diggs stars as Collin, who is three days from completing his parole after an assault charge landed him in prison. Meanwhile Casal stars as Miles, who grew up alongside Collin in a predominately black, working class neighborhood in Oakland. Real life childhood friends, Diggs and Casal bring a believable, palpable sense of camaraderie to the film, and especially in the first half, as the two tool around Oakland observing signs of gentrification, Blindspotting feels a bit like if Seinfeld had been concerned with anything important. The humor tends to be pretty basic “ugh, hipsters” stuff, but there are some solid riffs, and Diggs and Casal mine a reversal of expectations particularly well. While Collin is not thrilled to see his neighborhood overrun with tech-boom beneficiaries migrating from San Francisco, he does enjoy the increased healthy food options that begin trickling into the neighborhood, and he likes the safer streets (all while worrying about upwardly mobile rents). But Miles is seething with an anger he cannot control as he is confused with the carpet-bagging interlopers he sees as destroying his home.

Miles is almost a caricature, with his Macklemore hair, grill, and neck tattoo—which later also appears on the neck of a wealthy tech bro, in one of the films better grace notes—but his dilemma is understandable. He’s proud of his working class roots, and he sees himself as part of a multi-cultural community that rich white people are destroying. His problem, though, is that he has not wrestled with his own whiteness, doing the thing a lot of white people do, which is assuming that class struggle trumps any other form of struggle, without considering how class intersects with race and gender. Blindspotting’s second half tightens up and starts spiraling as Miles becomes ever more violent in order to prove he is not part of the gentrifying wolves from across the bay.

As Miles spins out, Collin is trying to keep it together. Not only is he trying to keep his reckless friend from ruining his shot at freedom, after we learn Miles is the reason Collin went to jail in the first place, but Collin is also dealing with the onset of PTSD after witnessing a police shooting. A black ex-con, he is acutely aware the risk of coming forward as a witness poses, and yet maintaining his silence is unbearable. One of the film’s weaker elements is in the contrast of Miles’ and Collin’s respective dilemmas. Miles is almost willfully idiotic, while Collin is struggling with things beyond his control. At a certain point, it becomes difficult to understand why Collin keeps hanging out with Miles, when Miles is so clearly the cause of much of his strife, and Miles becomes downright unlikeable as he continues to jeopardize Collin’s wellbeing. Collin’s epiphany about Miles is the climax of the film, explicitly driving home the whole point of the thing, and yet it feels less like a dramatic moment and more like a cause for celebration as Collin FINALLY sees Miles for the endemic danger he represents.

Blindspotting is not nearly as out there as Sorry to Bother You, but it does have its own brand of uniqueness as Diggs and Casal frequently freestyle in lieu of dialogue. Both are capable spoken-word artists: Diggs is a Hamilton alum and Casal is a slam poet featured on Def Poetry. You have to have a tolerance for spoken word, though, as they will push the limit of how much you want to hear in a two hour span, and some of the freestyles are too on the nose. A late freestyle by Collin explains the film in a way it does not explicitly need to be explained, which feels like a rookie mistake in not trusting the other elements of your story to make the point. Overall, it’s a little bit of a messier debut than Sorry, but more often than not Blindspotting is a bold, freewheeling examination of race in class in gentrifying America.