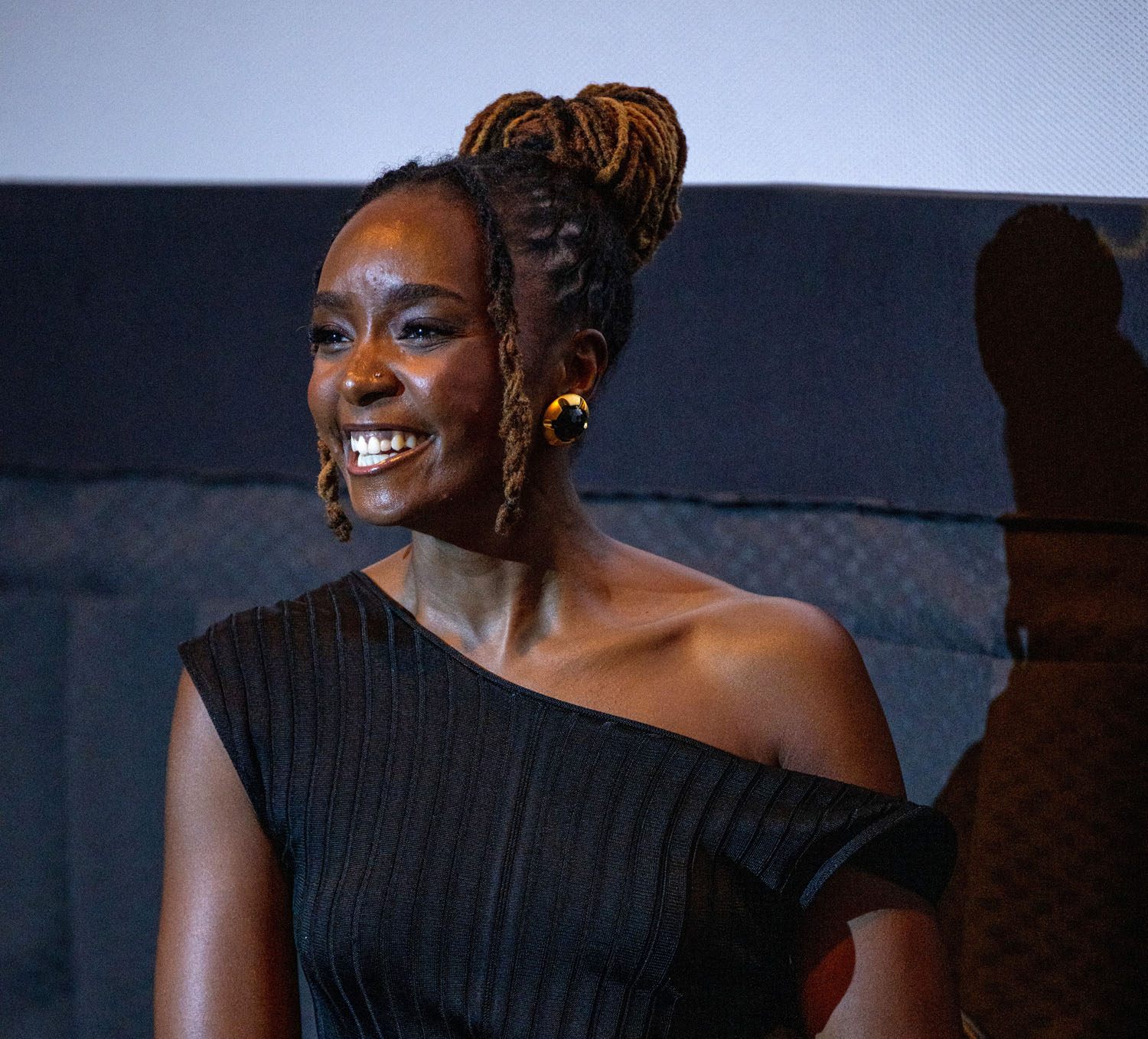

KiKi Layne in Dandelion

KiKi Layne is so naturally luminous on screen that a single closeup of her face can engender audience sympathy for her character. Filmmaker Nicole Riegel, directing Layne in her new film Dandelion, understands this quality in her star, and uses it to both make us care about her character and to test the depths of that sympathy as we watch her grapple with the limits of dreams.

In Dandelion, Layne stars as a singer-songwriter called Dandelion, government name Theresa, who is barely eking out an existence singing covers in a hotel bar in downtown Cincinnati to a deeply uninterested audience. She’s watching her dream of becoming a successful musician die in real time, and nurturing anger rapidly turning to bitterness after dropping out of a six-month tour to stay home and care for her ailing mother.

Dandelion isn’t doing anything new. John Carney’s excellent Once tread this ground nearly twenty years ago, and to better effect, but Riegel, who also wrote the script, knows what she has in Layne, which is a performer of unusual empathy and grace. Dandelion doom scrolls social media, taking in the less-than-talented “stars” who get by on their massive online platforms, but rather than scowl at her phone, Layne wears an expression of hollowed out despair—this is what music has come to, and Dandelion doesn’t want to play that game.

There is an interesting point raised mid-film about “making a living” versus music as “a way of living” which the film never really answers. Dandelion plays folk-rock, a genre not typically known to support Black artists, a point which Riegel subtly illustrates by showing a music shop decorated with photos of all the white men who define the genre. She later shows a photo of Tracy Chapman as a counterpoint…though Chapman didn’t get her first #1 single until Luke Combs covered “Fast Car”.

In the same vein, after Dandelion takes off for a battle of the bands at the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally in South Dakota—an improbable place for someone who looks like her and plays her brand of folk-rock—she meets Scottish musician Casey (Thomas Doherty), a white man with whom she begins writing new, fulfilling music. The film never really unpacks how Dandelion navigates the musical world. Riegel points out that there are Black singer-songwriters with significant careers, but there is no deeper examination of the state of the music industry for Black artists in America, and whether or not that might play into Dandelion’s stunted career growth, too. Similarly, Dandelion’s disconnection from a larger musical community is presented as a symptom of her isolation in Cincinnati, and nothing to do with being a Black woman playing a type of music dominated by bearded white guys and wispy white women.

Besides writing music together, Dandelion and Casey fall into a romantic affair, too. Casey, a guy with a bird tattoo, so you know he regularly disappoints everyone in his life, admits to being married but hints at a separation, which is a massive red flag Dandelion ignores. The music, the change of scenery, the people Casey introduces her to, all of it energizes Dandelion and brings forth new music and enjoyment in her craft, at least until Casey lives up to his walking red flag persona. It’s very obvious from the beginning how the romantic storyline will end, but Riegel still devotes a lot of time to showing the two musicians writing music together and frolicking in lush nature (this film pairs well with Luke Gilford’s National Anthem and Morissa Maltz’s Unknown Country for its luscious depiction of backroads America). Dandelion is at its best when depicting the creative process as a collision of wills and tastes and external inspiration.

The original music in the film comes from The National’s Aaron and Bryce Dessner, and the songs do sound like something you might hear on the radio. The music, like the film, is content to drift along and let KiKi Layne shine her light and lift it up. Dandelion would be more memorable if it had something to say about music and the place Dandelion finds herself, searching for a kind of old-school success in the social media age, and navigating a musical genre dominated by white artists as a Black woman. As is, it is a somewhat lightweight but enjoyable film that lets KiKi Layne shine for two hours, and there are certainly worse ways to spend your time than watching KiKi Layne.

Dandelion is now playing exclusively in theaters.