Romeo Must Die turns 20

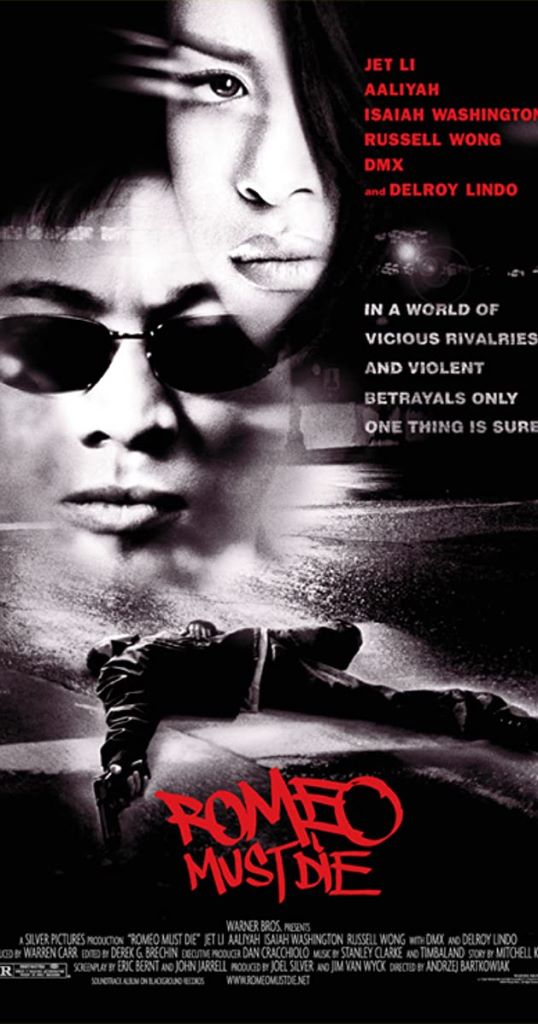

There was a time, in the mid to late 1990s, when I would watch anything even tangentially related to Romeo and Juliet. No, this was not inspired by Romeo + Juliet, it was inspired by reading Romeo and Juliet in middle school (though when the movie came out just one year after I first read the play, yes, I saw it ten times in theaters and was convinced it was the most romantic movie ever made). I fell in love with Shakespeare—I was basically Mandella from 10 Things I Hate About You—and in my teen years, Romeo and Juliet was extremely my sh-t. In 2000, I dutifully trooped to the theater to see a new action movie called Romeo Must Die, which promised to be a martial arts/action take on Shakespeare, starring Aaliyah and some guy called Jet Li. Romeo Must Die turns 20 on Sunday, so now is a great time to look back at the film that launched Jet Li in America and gave us a glimpse of what Aaliyah could have been, if the world were a little kinder.

First, as a person who has seen every possible iteration of Romeo and Juliet, you must know that Romeo Must Die has virtually nothing to do with Shakespeare. Aaliyah and Li star as Trish and Han, respectively, the children of rival gangsters in Oakland. That is where the similarities to Shakespeare end. Trish and Han are not star-crossed lovers, there is no Mercutio, and no one gives the “Plague o’ both your houses” speech, nor is there an “All are punished” moment—the older I get, the further Romeo and Juliet slides down my list of favorite plays, but man, those two lines are spine-tingling every time. It’s not Romeo and Juliet without them, and Romeo Must Die does not have them, therefore, this is not really Romeo and Juliet.

But it IS the movie that introduced me to Jet Li, and started an obsession with Hong Kong cinema. Romeo Must Die isn’t romantic—Aaliyah and Li do not have great chemistry—and it hasn’t aged especially well, but there is no denying how f-cking fun it is to watch Jet Li work. And it is painful to look back now and see Aaliyah, and what a total f-cking star she was. Romeo is her first acting credit and she is already dominating the screen with pure charisma and talent. Her legacy is a giant question mark of what could have, should have been, but Romeo makes clear she would have been something remarkable. She can uplift a mediocre action movie, she’s absolutely compelling, and the climax of the movie gives her some scenery to chew, which is the barest taste of what she could have been as a dramatic actress. (Lainey: and also… Aaliyah on that soundtrack!)

This movie came out one year after The Matrix, so its use of wire-assisted martial arts is easy to dismiss as a Matrix knock-off, but really, The Matrix borrowed heavily from Hong King cinema, and Romeo Must Die is rooted in the kind of movies Li was making in Hong Kong in the 1990s. It’s more apt to say that Romeo and The Matrix share influences than to say that The Matrix influenced Romeo. Visually, Romeo doesn’t hold up super well. Wire-assisted martial arts look undeniably fake, and given the constant parodying of The Matrix in the 2000s, the technique also looks incredibly dated now. But when Li is just doing his thing on the ground, Romeo looks as good as any contemporary action movie. This is also an action movie that builds a fight sequence around an injury, something we don’t see a lot in American action cinema. We like our action heroes to be indestructible badasses, but Romeo Must Die isn’t afraid to let its hero fall down, even get hurt.

Most imported action stars, like Arnold Schwarzenegger, Dolph Lundgren, and Jean Claude Van Damme, conform to the American standard of the indestructible badass. Even Jackie Chan, who broke through with Western audiences a few years before Li with 1995’s Rumble in the Bronx, has a style closely related to Buster Keaton, which makes his films easily accessible to Western audiences. But Li comes from a tradition of grind-em-up actioners where heroes take on damage and keep going, adjusting constantly to new circumstances as injuries pile up. The contemporary extension of this is Iko Uwais in The Raid, which is then translated by American filmmakers as John Wick.

Romeo Must Die sticks out in 2000, the year that launched the superhero boom with X-Men, and included action movies that ran the gamut from Arnold Schwarzenegger’s intolerable 6th Day to Jackie Chan’s Shanghai Noon, to Oscar-winning Gladiator. American action movies in 2000 were a mess as Hollywood transitioned from the increasingly improbable actioners of the 1980s and 1990s to a more grounded style heavily influenced by Hong Kong action—a trend driven by the arrival of John Woo in the US in the early 1990s and his string of incredibly stylish if also immensely stupid Hollywood action movies (Face/Off, I still love you).

Look past the terrible Y2K fashion and barely-there gangster plot, and Romeo Must Die is actually a glimpse into the future of action movies. Parts of it are dated as hell, but those fight scenes start, and you can’t help but see elements we didn’t borrow consistently in American action movies until the 2010s. Romeo Must Die is an interesting little time capsule: it’s Jet Li’s first leading Hollywood role, Aaliyah’s first acting performance, it’s a movie that is both dated and prescient of contemporary action cinema, and it introduced Western audiences to one of the biggest action stars in the world and helped cement the Hong Kong style in American action cinema. I went into Romeo Must Die thinking I was supporting my Shakespeare love, but I came out a Jet Li convert.