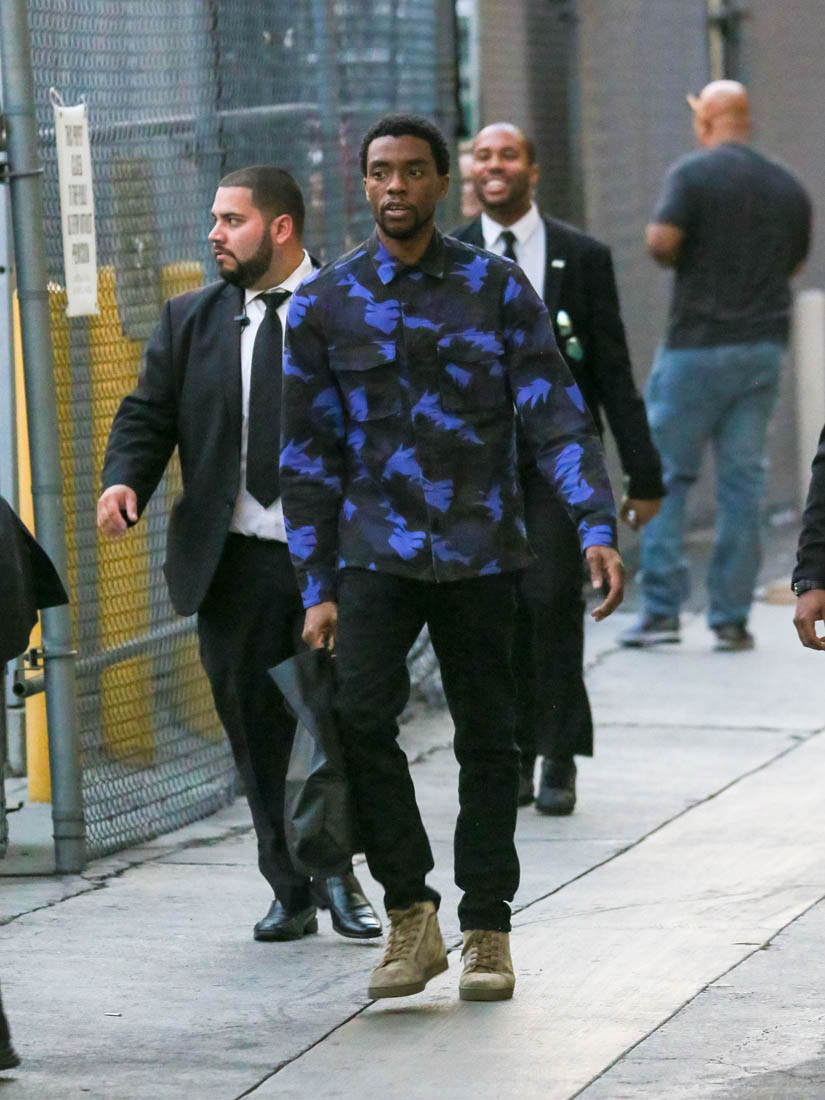

Chadwick Boseman in Marshall

Set in 1941, Marshall depicts the early days of Thurgood Marshall’s law career, before he tried and won Brown v. The Board of Education—which desegregated schools in the US—and before he became the first black Supreme Court Justice. The case in question is Connecticut v. Joseph Spell, in which a black chauffeur was accused of raping Eleanor Strubing, the white woman for whom he worked. It could not have looked worse: Spell had been fired from his previous job for stealing, he was dishonorably discharged from the Army, he had abandoned his wife and children in Louisiana; meanwhile, Eleanor Strubing was old Philadelphia money, married to an Ivy League football hero, and had never stepped a toe out of line in her life. Connecticut was not the land of Jim Crow, but there was still plenty of prejudice to go around, and the case was making headlines as hateful stereotypes were trotted through the presson a daily basis. Enter Thurgood Marshall.

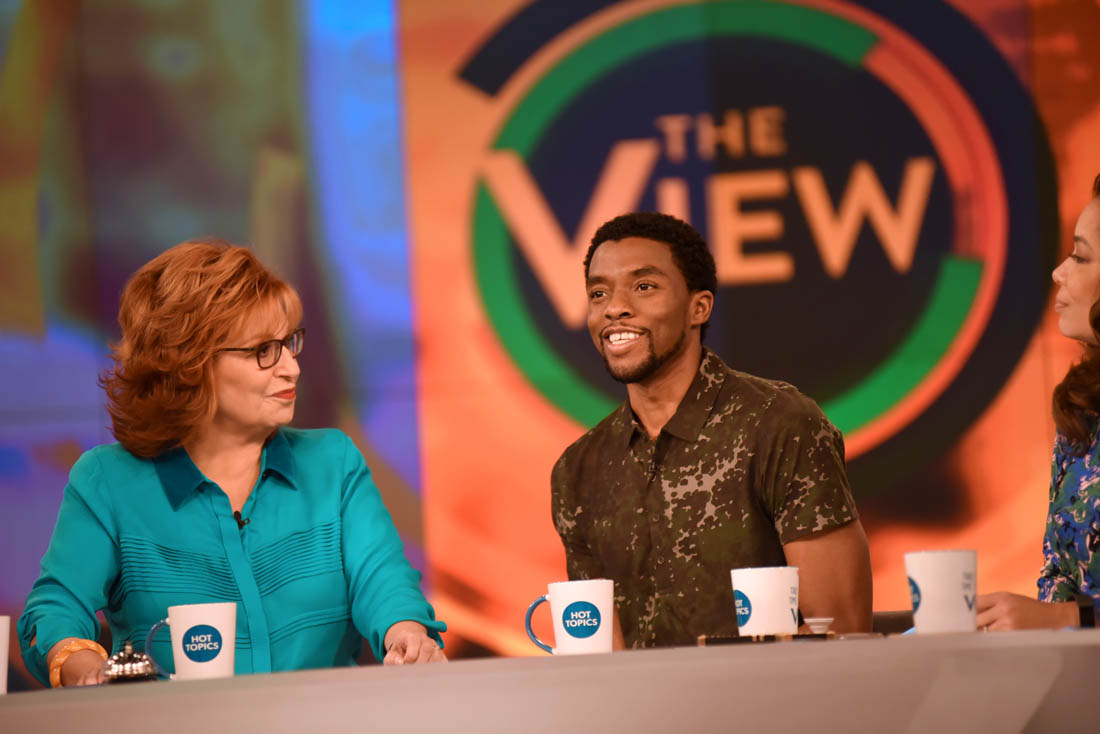

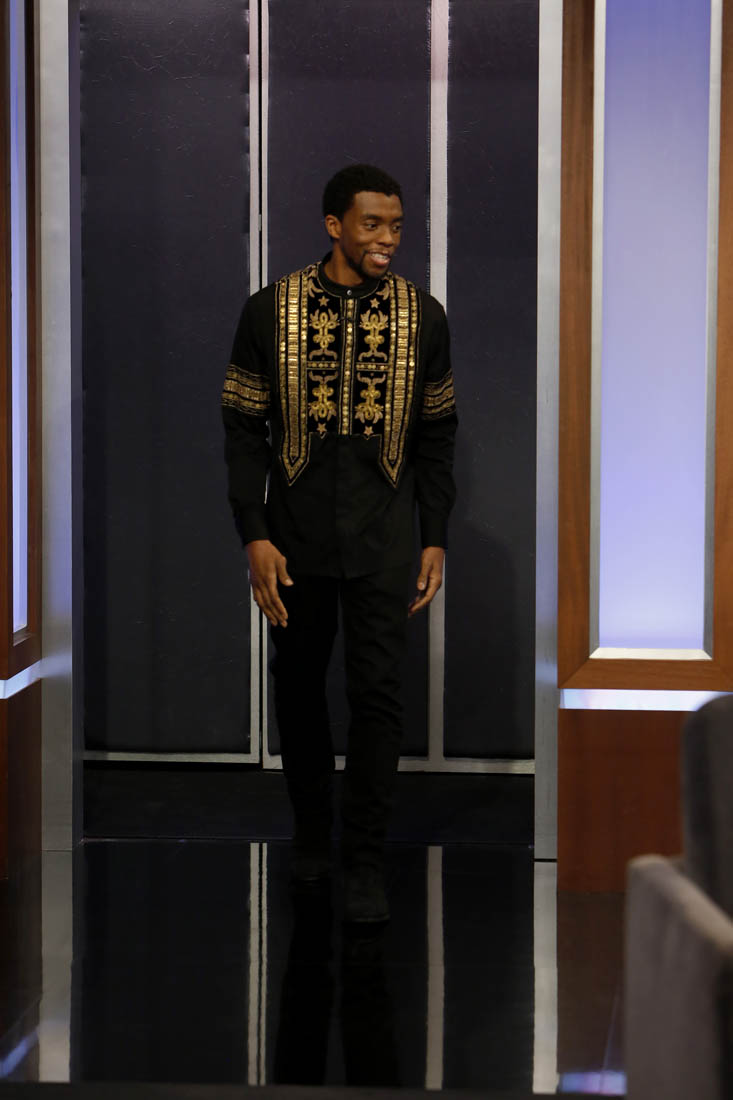

The film presents Thurgood Marshall (Chadwick Boseman) as a gifted orator and brilliant legal thinker—which he was—but only lightly touches on his reputation as a womanizer. Marshall makes a few choices that are very odd, but casting Boseman isn’t one of them—he’s great. His natural charisma cuts through the patina of history to make Marshall tangible, not carried off into the realm of the untouchable Great Man of History (this is why he keeps getting cast in biopics—his magnetic intensity grounds his characters and makes them viscerally flesh and blood).

But it turns out that the way the case is presented in Marshall is mostly bullsh*t, and the dramatic license taken just makes you wonder why this case was chosen in the first place. The film would have you believe that Marshall, upon applying to be admitted to the Connecticut State Bar, was denied by a prejudiced judge (James Cromwell). Thus, the case fell to inexperienced trial lawyer Sam Friedman, a Bridgeport local, to try the case while Marshall sat second chair, forbidden to speak during trial. This set up is meant to show Marshall as a canny thinker and master manipulator, but it mostly just gives Friedman (a miscast Josh Gad) way more screen time than anyone not named “Thurgood Marshall” needs. In reality, Marshall never applied to try the case, he went to Bridgeport merely to consult. Sam Friedman was, in fact, an experienced trial lawyer, noted for his flair with juries—which surely helped with a case like Joseph Spell’s.

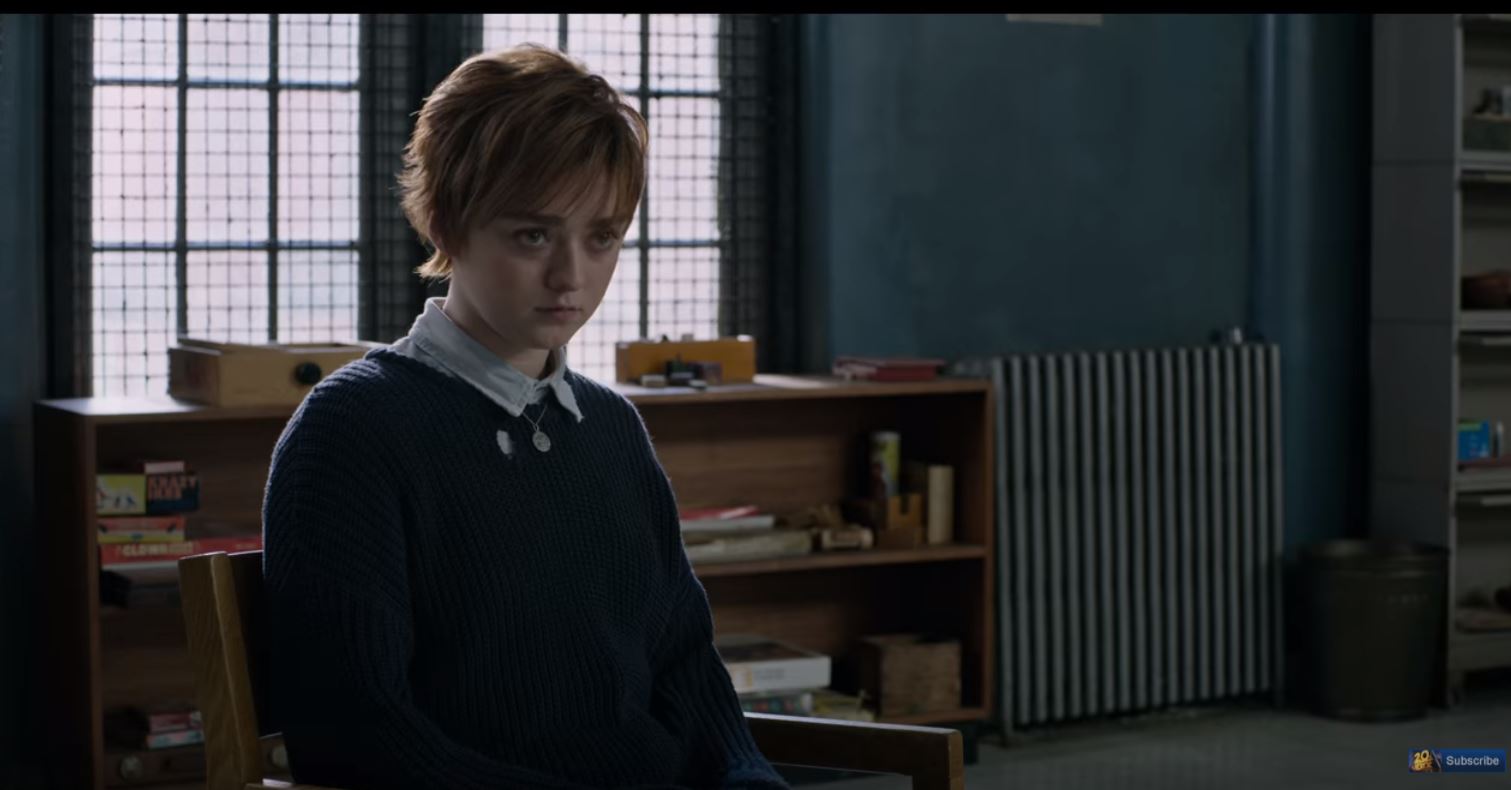

This is where Marshall gets tricky. On one hand, the trial scenes are very good, and Marshall is well structured and paced as a legal thriller. Marshall and Friedman work to solve the case—since no one else is—and figure out why Eleanor Strubing (Kate Hudson) lied about being attacked, and the way it unravels in the courtroom is really effective in the moment. But on the other hand, the entire case rests on proving a woman lied about being sexually assaulted. The film sets it up in a way that is meant to be sympathetic, but there’s just no getting around how deeply uncomfortable it is to watch lawyers figure out how to discredit an alleged rape victim. (And it’s colossally bad timing for such a narrative.)

So we’re back to wondering why this case was chosen in the first place. The writers are Michael Koskoff and Jacob Koskoff,a father-son pair from Bridgeport, Connecticut, and Michael is an attorney, so this story is in their orbit as a piece of local legal history. But the minute they brought the screenplay to producers, someone should have said: “A Thurgood Marshall biopic, great idea! This is entirely the wrong case to use.”

“Thurgood Marshall biopic” and “legal drama about complicated sexual assault case” are two different movies. A movie about the Joseph Spell case would feature Thurgood Marshall as a minor player, while a Thurgood Marshall movie should use, if not Brown v. The Board of Education, then at least a case Marshall actually got to try himself. Using the Joseph Spell case in a Marshall biopic divides the narrative between two complicated elements, and the attempt at decluttering the story renders the Spell case a borderline disastrous oversimplification with gross modern context, which in turn takes away even more from Marshall’s accomplishments.

Thurgood Marshall spent his early career travelling the US, trying cases under impossible circumstances, always having to stay one step ahead of literal lynch mobs—he was a goddamn legal Avenger. He deserves a great biopic, and Marshall is at least engrossing, as long as you can swallow the knee-jerk revulsion for the tone of the legal defense. But it’s only a Thurgood Marshall biopic because the movie is titled “Marshall”.