Intro for September 12, 2025

Dear Gossips,

Walter Benjamin was a cultural critic, essayist, and philosopher who published “The Work of Art in the Mechanical Age of Reproduction” in 1935. Benjamin believed that increasingly easy means of reproduction devalued the “aura” of original works of art, that a print of a painting could “travel” to places the original work could not, thus lessening its inherent cultural value. I didn’t agree with Benjamin on that point when I was an art student, and I still sort of don’t agree with it now—not everyone can afford to travel to Paris to visit the Louvre, but online simulators at least give people something like the experience, and that access is not inherently bad—but I recently re-read Benjamin’s essay and, well. That dude saw the future.

I am vastly oversimplifying Benjamin’s work, but he divided art into two values, “cult” and “exhibition”. Cult value is based on authenticity and limited access, think of statuary built into great cathedrals, temples, or tombs which are fixed in place and limited in access. Ghiberti’s iconic bronze doors known as the “Gates of Paradise” were made for the Florence baptistry, where they were cult objects intended to excite religious parishioners. But they have been moved, now they sit in the Duomo in Florence, while copies fill the northern entrance of the baptistry—exhibition objects. Are Ghiberti’s doors less valuable since copies have been made and the originals no longer serve their intended purpose? Or has their value simply shifted from cult to exhibit? That is the heart of Benjamin’s inquiry.

I didn’t entirely agree with Benjamin back in the day, but I cracked open my copy of “Mechanical Age” recently because maybe Benjamin underestimated “industrial” art forms like photography and cinema, but he absolutely predicted the devaluing of art in the digital age. Benjamin just anticipated the moment, his “mechanical reproduction” less about cameras and more about computers. When I think about Benjamin’s assertions in relation to AI, “content”, and the corporate death spiral the film industry is willfully engaging in, I think he was completely, entirely right.

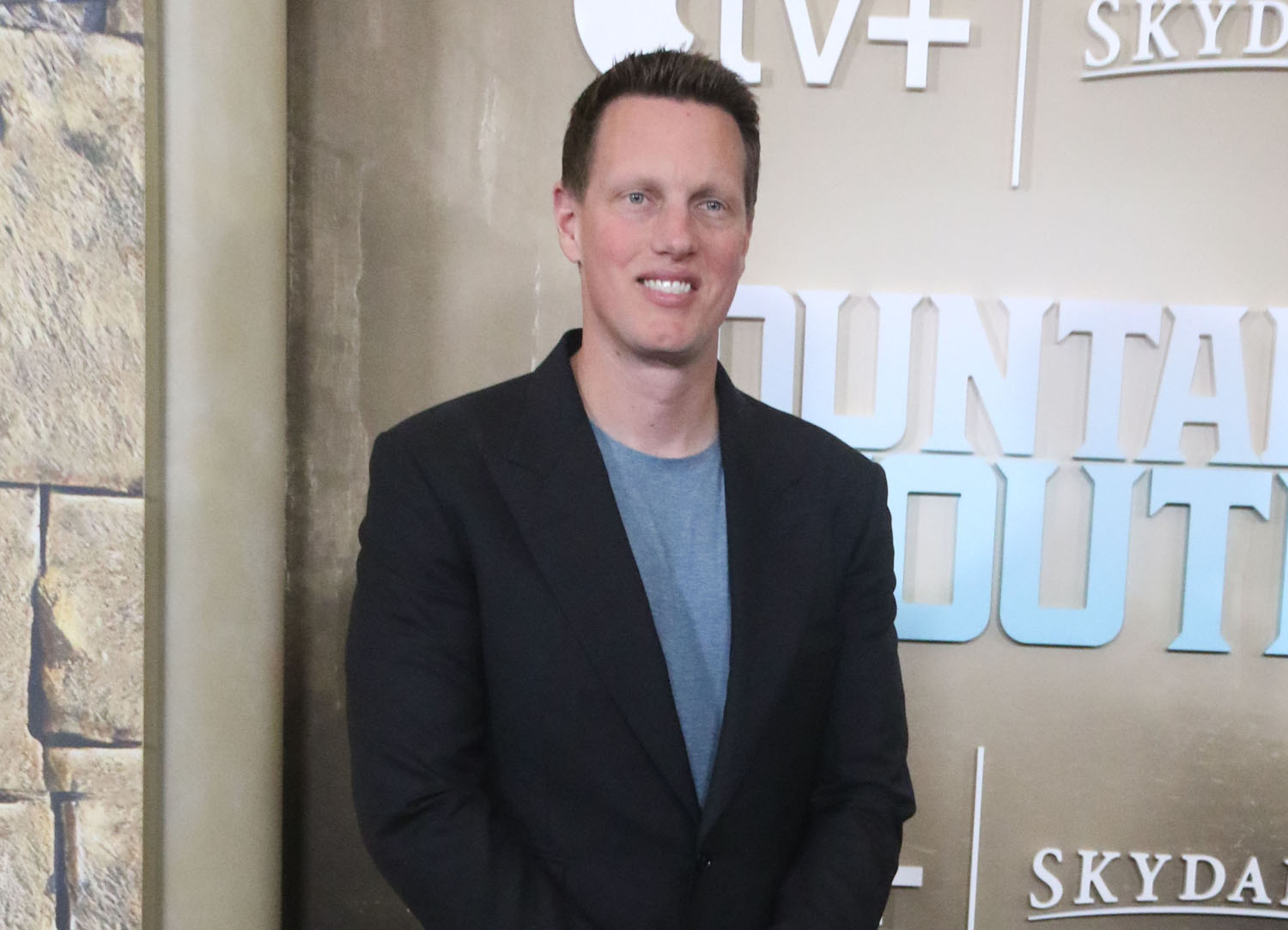

The latest doom news is that Paramount Skydance, fresh off their cursed merger, is preparing a bid for Warner Bros. Discovery. This seems blatantly anti-trust, just like the Disney-Fox merger, but also like that merger, who’s going to stop it? Certainly not the pro-big-business current administration. If it happens, this will reduce the number of major film studios from five to four—ten years ago we had six.

It's part and parcel of newly minted Paramount Skydance CEO David Ellison’s plan to remake his movie studio into a tech company. Why is everyone in Hollywood obsessed with being a tech company? Probably because money flows more easily in Silicon Valley, and the CEO class is made up of superrich Davos bros who dream of passive income produced by tech stocks, like that of Larry Ellison, David’s dad, whose net worth spiked $100 billion in one day when Oracle stock ticked up.

All throughout TIFF I was thinking about the future of cinema, where it’s going and what it all means, why are we even doing this dance anymore, when everyone says movies are dead? But then I was in Hamnet, listening to hundreds of people sob throughout the film; I was in Tuner listening to everyone gasp and watching people literally lean toward the screen in critical moments. Film ISN’T dead, audiences ARE engaged, you just have to get the movies to the people. But there’s less and less interest in that, what the current ruling class of Hollywood wants are the kind of big returns they see in the tech industry, but Hollywood isn’t built to deliver that. A movie studio isn’t a stock paradise, it’s a horse racing stable, you turn out hundreds of prospects in the hopes of finding one Kentucky Derby winner.

They don’t want to do that anymore. They want algorithms to predict hits and if they can’t do that, they’ll turn on AI to make endless slop that won’t nourish us as art is intended to do, but will occupy our eyeballs, keeping us on their apps and platforms for hours every day. They don’t want to greenlight films that might generate cult value by becoming rarified markers of cinema, they want the basest exhibition value of cheaply made, easily consumed, quickly forgotten ephemeras to drive stock prices up and up and up, while the rest of us starve, our inner lives devastated by empty cultural calories. Walter Benjamin saw the writing on the wall, he just didn’t get the means of reproduction right. But his mechanical age is here now, and it’s a nightmare.

Live long and gossip,

Sarah