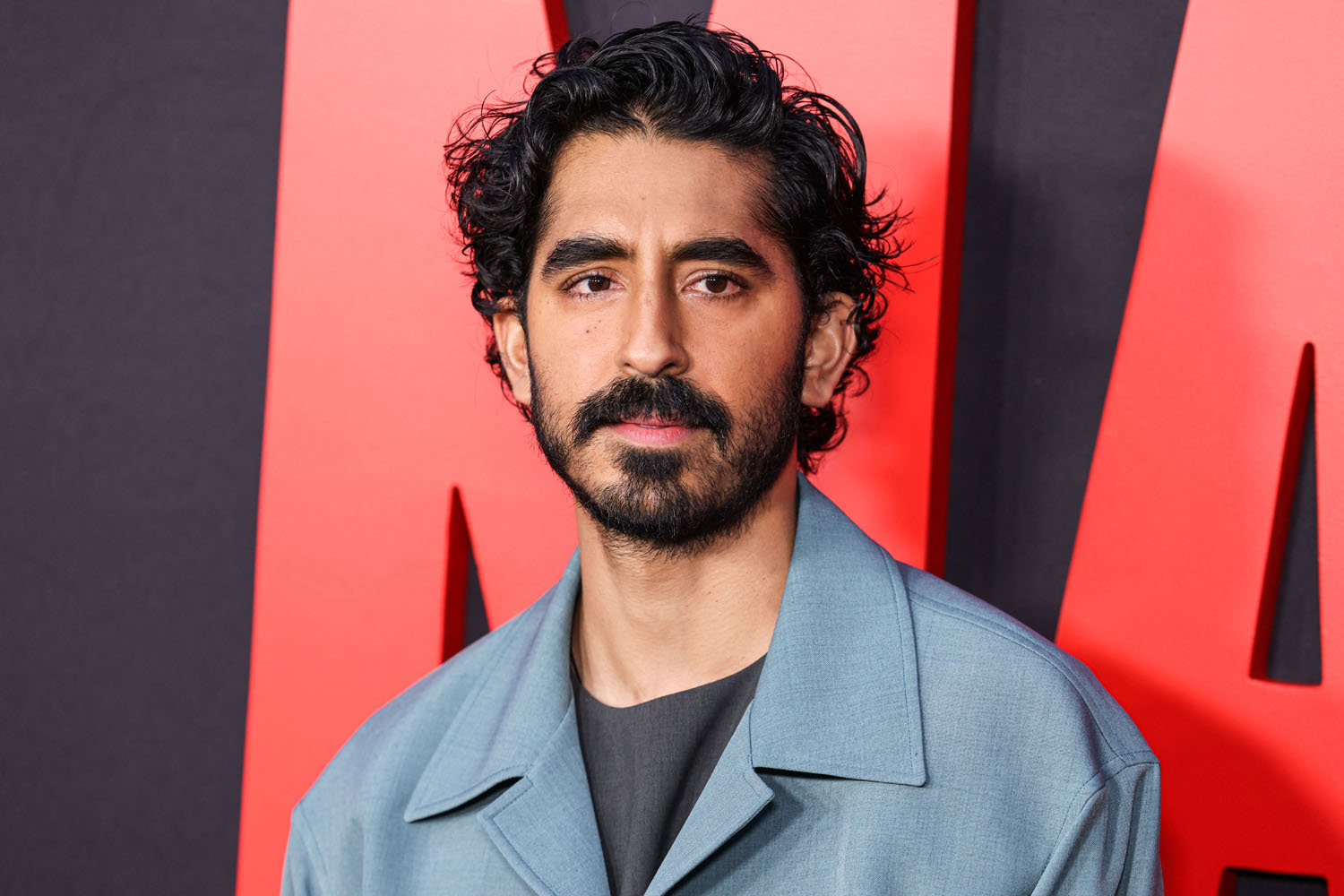

Dev Patel’s Monkey Man

Dev Patel makes his directorial debut with Monkey Man, a blazingly ambitious revenge thriller that is an immediately impressive calling card for Patel as a very talented filmmaker. Working from a script he co-wrote with Paul Angunawela and John Collee, Patel directs and stars in the film as a man known only as “Kid”, a nobody living at the bottom of society in the fictional Indian city of Yatana. The Kid makes money losing fights in an underground fight club—Sharlto Copley pops up as the shady ringmaster—and one day gets a job washing dishes at an exclusive club run by a woman called Queenie (Ashwini Kalsekar).

Subtlety, thy name is NOT Dev Patel. He misses no opportunity to draw parallels between the Kid’s ascension through the ranks of club staff and India’s social caste system. The higher you go up the club’s multi-floor building, the nicer it becomes, yet the club runs on a system that is inherently corrupt and exploitative, designed to keep the “have-nots” at the bottom while indulging the “haves” every whim and desire. Drugs, sex, it’s all for sale at Queenie’s. The Kid certainly notices pretty sex worker Sita (Sobhita Dhulipala), but he really gets hung up on Rana Singh (Sikandar Kher), a club VIP and the chief of police.

Intercut throughout Monkey Man are flashbacks to the Kid’s childhood in a lush green forest, those idyllic memories interrupted by others of flames and screaming. Eventually, the story is pieced together, and we understand that the Kid is avenging the murder of his mother, which also means taking on the elite of Yatana’s society. Though Monkey Man drops a John Wick joke early on—it only works because we’re all making the comparison anyway, and a spot of self-awareness goes a long way when the influences are so clear—the first half of the film features the Kid getting his ass kicked a lot. He’s not the smooth powerhouse of John Wick, nor the flashy fighter of The Raid—another obvious influence—at least, not to start with. That comes later, after the obligatory yet imaginative training montage.

Patel proves not only a capable leading man in an action movie—his physicality is absolutely believable, especially since the Kid ISN’T always winning every fight—but also a very capable director. There’s a little bit of actor-director showiness, a “look ma, I know what cameras are” tendency to move the camera a little too much, but there is also a wild amount of style and confidence in his choices. For instance, Patel and cinematographer Sharone Meir often choose to follow a fist, a foot, or a knife through a fight sequence, and there are first-person POV shots of people taking punches or being thrown over tables. The result is visceral and dizzying, placing the audience in the immediate action.

It’s effective, but it does undermine the well-choreographed and performed action scenes. There are times when you just want to watch what is clearly a capable crew of stunt performers do their jobs well, but the camera is sliding away, following momentum, not scenery. It’s A Choice, and it’s one Patel makes and sticks with to elicit a certain effect, but it does step on his own toes a little, taking away from the thrill of watching a good fight unfold, uninterrupted. There are moments when you sort of want Patel to do a little less, let the scene breathe, give more space to the action performances, but his choice does serve the propulsive action, even if it gets in the way of the choreography.

But when Patel lands on the big images, he lands HARD, and to great effect. He has a spectacular eye for color, light, and shape, which he uses for everything from lovingly filming the preparation of street food, to the movement of traditional Indian garments in action, to shattering people’s jaws with serving trays. There are some breathtaking sequences and images, perhaps none more purely thrilling than the moment a commune of hijra, or trans and intersex people, join in a fight and get a hero moment as glorious as any superhero.

Narratively, Patel displays great empathy for the marginalized groups of India, whether it’s Muslims or hijra, forced to the edges of society. The big bad of Monkey Man is Rana Singh, but he’s emblematic of a nationalistic government led by a religious guru, Baba Shakti (Makarand Deshpande), who preaches peace and love but has made a fortune exploiting land and workers and incites nationalistic violence against any who do not conform to his preferred societal model. The parallels to real problems in India and their current government are clear, even if Patel set his movie in a fictional city, probably to avoid drawing the ire of said government.

Monkey Man is a purely entertaining revenge thriller, but it has more on its mind than punches and kicks. Woven into the film is the myth of Hanuman, the half-man, half-monkey god who fights the other gods on behalf of the downtrodden. Again, it’s not subtle, and Patel takes every opportunity to reinforce his point, from incorporating high and low art, nature imagery, ironic pop music and unironic death metal, and even a side trip through psychedelia that would do David Lynch proud. There is so much talent on display from Patel it’s almost overwhelming, but the film itself is working on such a grand mythic scale that it works. Dev Patel has long been regarded as a good actor, but Monkey Man announces him as a serious and seriously talented filmmaker, too.

Monkey Man is now playing exclusively in theaters. The dog does not die.