Grief takes center stage in Black Panther: Wakanda Forever

Usually, the star of a film gets the headline for the review, but in Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, grief IS the lead character. Dealt the incredible loss of his friend and collaborator Chadwick Boseman, director Ryan Coogler finds a way to marshal on in the world of Wakanda, though the film is haunted by the absence of Boseman, and not just as a story point. Coogler, who co-writes the script with Joe Robert Cole, shifts the focus from Boseman’s King T’Challa to the women of Wakanda, the family and friends left to pick up the pieces after the death of T’Challa (and Boseman in real life). Grief weighs heavily on the film, and in some moments, it does not feel like anyone is acting but that their raw, real grief is being recorded for posterity’s sake. At times, Wakanda Forever feels invasive and like all of these people should be left alone to grieve in private.

Which makes turning the focus to Wakanda’s problems on the world stage a particularly smart decision from Coogler and Cole. T’Challa is gone, but Wakanda can’t just withdraw into the shadows. They’re known now, and life goes on even as Queen Ramonda (Angela Bassett) and Princess Shuri (Letitia Wright) are still reeling from their loss. Ramonda, the queen regnant now, must deal with global threats to Wakanda’s independence and the increasingly isolated and uncomfortable spot they occupy on the world stage. Richard Schiff shows up as an unnamed U.S. Secretary of State sweatily zealous about “destabilizing” Wakanda to get at their precious vibranium. Coogler addresses the inevitable fallout of Wakanda upsetting the world order and knocking America from the top of the world power heap by flat-out stating what America does to countries that have resources it wants.

But the problem for Wakanda isn’t America, at least, not yet. The more immediate problem is from an unknown threat rising from the sea. So, while grief rests like a mantle on Wakanda Forever, there is no time for these characters to slow down and sit with it. They must deal with what comes to them, which both feels like an apt metaphor for carrying on in the face of immeasurable loss, and a little bit like a narrative mistake. The emotional resonance of Wakanda Forever cannot be denied, and as a portrait of grief—terrible, howling, endless grief—it is deeply moving. But as a story? It doesn’t hang together as tightly as Black Panther. There’s a little too much going on, and the movie is definitely too long. Wakanda Forever, besides being a vehicle for the friends and co-workers of Chadwick Boseman to process their loss, is also saddled with doing some heavy lifting for future MCU projects. It’s got an unfortunate case of Iron Man 2 syndrome.

One plot that could be cut is Everett Ross (Martin Freeman) and his new boss at the CIA, Valentina de Fontaine (Julia Louis-Dreyfus), arguing over how to handle Wakanda. It’s not that Freeman and Louis-Dreyfus aren’t enjoyable, they are. And stretching Ross’s loyalties between his country and the life debt he feels toward Shuri and Wakanda is interesting, but this isn’t really the place for it. Tuck that subplot somewhere in the upcoming Wakanda-set Disney+ show, and don’t make Wakanda Forever worry about Everett Ross. This movie has enough to carry without him. And, unfortunately, the same goes for Riri Williams (Dominique Thorne), making her MCU debut as Ironheart.

Thorne is perfectly charming, and she essentially serves the same role Bucky Barnes did in Captain America: Civil War, being the Macguffin everyone is chasing. But Bucky worked in that context because he had a personal connection to both protagonists, which deepened the emotional impact of the third act. But Riri has no personal connections to anyone in this film, she could be a glowing box of secrety secrets and nothing about the movie changes. Wakanda Forever is too long and overstuffed and simply removing Riri and the CIA subplots would go a long way to fixing both those problems. It’s enough this film has to bear the burden of Boseman’s loss, don’t make it set up four future MCU thingamajigs, too.

What does work exceptionally well, besides the theme of loss and mourning, is the arrival of Namor (Tenoch Huerta Mejía), and his people, the sea-dwelling Talokanians. Like Wakandans, the Talokanians retreated from European imperialists and hid away, taking refuge in the sea and adapting to life underwater. Namor is an anti-hero in the comics, rarely aligning his goals with the surface world, and here he is a flat-out antagonist to Shuri and the Wakandans. What Coogler and Huerta do supremely well, though, is ground Namor’s grievances in fully understandable, even sympathetic reasoning. He has more in common with Shuri and Ramonda than not, and Wakanda and Talokan should make natural allies. That they come to blows feels like a real tragedy, a legitimate failure of not only leadership, but empathy as well.

And Huerta is brilliant as Namor, shifting easily from enticing, even borderline flirty appeal, to a menace that is no less palpable for his subtlety (although Namor is also good at issuing open threats and backing them up in spectacular fashion). But even though Huerta and Bassett and Wright, and the rest of the ensemble, are all very good, no one can fill the void left by Boseman. Turning Wakanda Forever into a meditation on mourning works, more from an emotional standpoint than a story one, but it really drives home how big Boseman’s presence is in the first film, and how no one, not even a collection of actors this good, can replicate the power of his charisma on screen.

No one is also capable of replicating his role as protagonist, as the film speed-runs Shuri’s character development to push her into a place where her third-act actions are believable. It only sort of works. Wright was cast as a comedic foil to Boseman’s stately presence as T’Challa, and Shuri was, up until now, mostly comic relief for her brother, a perfect straight man. Wright gives a great performance, but Shuri’s development feels rushed and undercut by the narrative necessity of the character arriving at certain decisions before she gets there organically. It feels like two movies of development crammed into about an hour of Shuri-centric storytelling in the film.

Wakanda Forever is unfairly burdened. The loss of Chadwick Boseman obviously unmoored his friends and collaborators, and as a paean to Boseman, and T’Challa, Wakanda Forever works beautifully. But the film is also stuck doing some narrative expansion for the MCU that would have been better left to other works. Wakanda Forever is best as a love letter to a fallen friend, and as a kind of conduit for public grief. All of its weak points come from serving the larger franchise’s ongoing story. Like Wakanda itself, Black Panther: Wakanda Forever is better off left to its own terms, to exist in its own space and not worry about outsiders. It is enough to remember, to mourn, to celebrate the life and legacy of Chadwick Boseman and T’Challa. We’ll have more discussion on Wakanda Forever next week when more people have seen the film.

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever is exclusively in theaters from November 11, 2022.

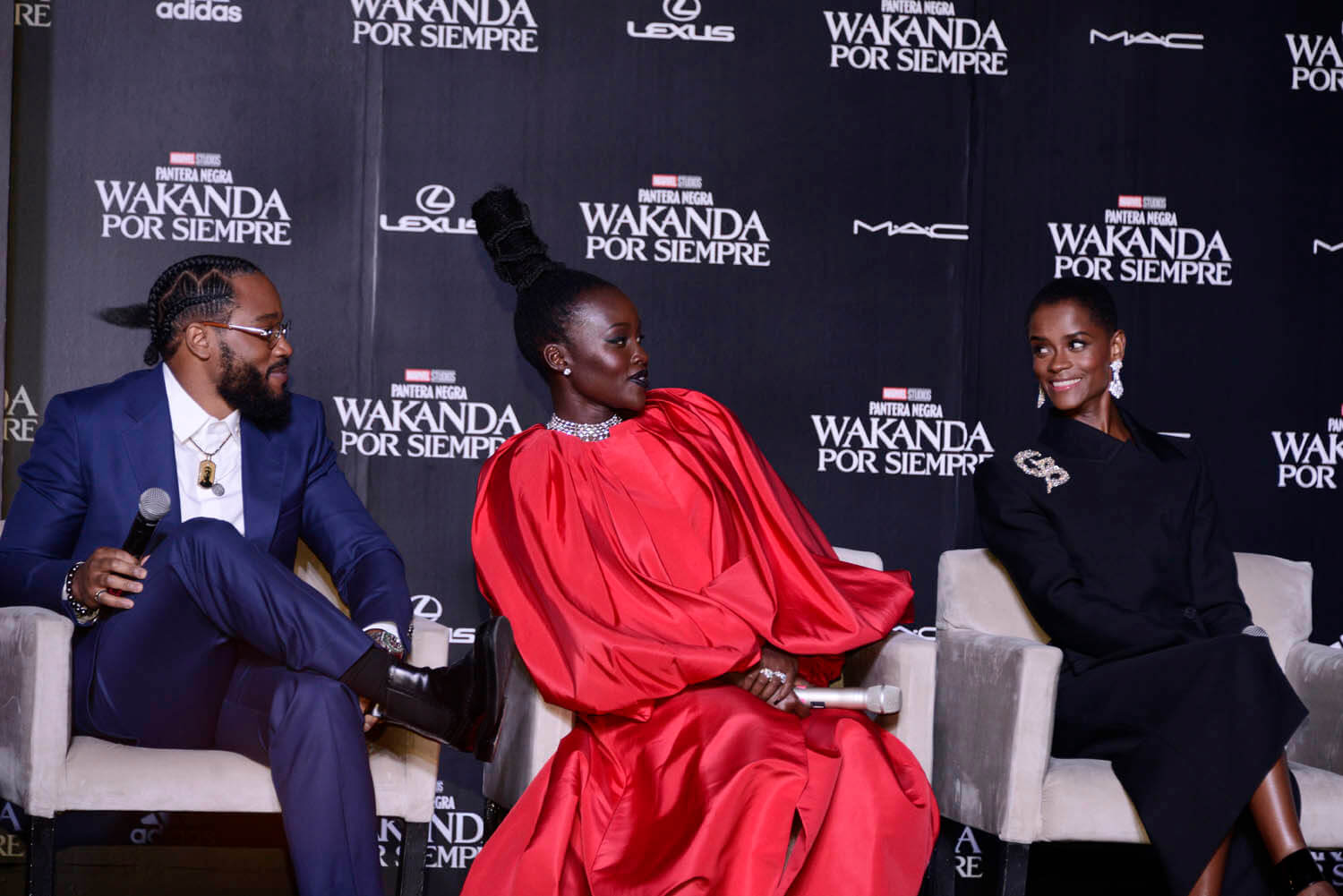

Attached: Ryan Coogler, Letitia Wright, and Lupita Nyong'o promote Black Panther: Wakanda Forever on November 9, 2022 in Naucalpan, Mexico.