Blake Lively in It Ends With Us

Films about difficult subjects do not have to be visually drab affairs, as if underscoring the seriousness of the subject by rejecting the inherent glamour of cinema, but by the same token, films about difficult subjects should at least FEEL like they’re about difficult subjects. It Ends With Us, an adaptation of Colleen Hoover’s wildly popular novel, struggles mightily under the hefty weight of its subject matter—domestic violence and intergenerational trauma.

Faithfully adapted for the screen by Christy Hall (who also wrote the excellent and nuanced drama Daddio, and the teen fantasy/drama I Am Not Okay With This, works strong enough that I am hesitant to put all of It Ends With Us’s failures on her shoulders), and directed by Justin Baldoni, who also stars in the film, It Ends With Us traces the romantic trajectory of the comically named Lily Bloom, a flower-obsessed woman whose life is defined by intimate partner violence, first as witness to her parents’ violent marriage, and later within her own troubled partnership. Teenaged Lily (Isabela Ferrer) seeks refuge with her classmate Atlas (Alex Neustaedter), whose own home is unsafe, too, which drives him to live in an abandoned house, instead. Atlas is Lily’s first love and first everything, though they inevitably part ways.

As an adult, Lily (Blake Lively) relocates to Boston, a city she has always dreamed of living in, yet the film is singularly uninterested in exploring. Ends presents as a Hallmark film, with plenty of establishing shots of its named location, but it is very obviously filmed Somewhere Else. “Boston” is a stand-in for big city glamour with a down-home attitude, the kind of place where people consume gallons of homey soups, but no one ever talks endlessly about their sport teams. There, Lily opens a flower shop straight off a Pinterest board, keeping alive the cinematic tradition of romantic heroines running charming small businesses that never have any customers.

While pondering a CGI Boston skyline, Lily meets Ryle—everyone in this movie has a stupid name, it’s distracting—a handsome stranger whose introduction is made by hurling patio furniture around a rooftop. It is no judgment on the film that Lily ignores this red flag and instead flirts with Ryle, who is played by director Baldoni with soap opera seriousness and perma-stubble. Despite Lily stating she doesn’t want a relationship with him, Ryle eventually wears Lily down and she begins a relationship with him. Again, this is not inherently bad storytelling.

Part of Ends wants to show how insidious intimate partner violence is, that it isn’t all screaming and fights, that abuse can happen both subtly and slowly, and that people can excuse and even outright ignore incidents of violence because they aren’t the day-to-day norm. Though Lily’s guard is initially up due to her own traumatic childhood, she still doesn’t see the trap closing around her as Ryle tightens his grip, throwing violent tantrums when confronted with a now-grown Atlas (Brandon Sklenar, sporting a similar stubbly appeal, Lily certainly has a type) reentering Lily’s life. This could have been a searing portrait of how domestic violence seeps through the cracks of an otherwise confident persona, but then…

There is the strange tonal clash of Lily’s precarious home life and her absolutely thriving romantic life in which two successful men vie for her attention. It feels like half of Ends wants to be that serious examination of a fraught subject, but half just wants to be an endless parade of Lily’s floral outfits and sparkling repartee with the men courting her. That part of the film recalls Lively’s romantic fantasy film, The Age of Adaline, a film with a premise so bananas you can easily abandon yourself to its whimsical charms and overlook narrative inconsistencies in favor of going along with the fantasy.

Here, though, it’s much harder to overlook the inconsistency because it’s about the depiction of domestic violence. The topic is simply too serious for frivolity. But though the younger actors nail the wistfulness and anxiety of young people negatively impacted by circumstances beyond their control, the adults simply do not have the grounding to make any of this work. Lively wears her extravagant wardrobe well—though the excess of working brand Carhartt makes me think someone wanted at least some of her clothes to say “relatable”—but she’s less effective here than she was in Adaline, simply because she does not have the gravitas to sell Lily’s heavier moments.

Similarly, Sklenar and Baldoni are both hamstrung by cheesy dialogue and a lack of characterization. Adult Atlas is simply a trope, the good guy who shows up to love the heroine no matter what and save her whenever necessary. And anything Baldoni manages to build out of Ryle’s two-faced personality, switching between controlling and charming, is completely undone by a late-stage plot reveal that essentially excuses Ryle’s violence. It’s maddening anyone—Colleen Hoover, looking at you—even felt the need for a “reason” for Ryle to be violent. We just spent two hours watching this guy physically and mentally break down Lily, do we NEED to like him? The film reaches for a happy ending it doesn’t need and definitely doesn’t earn.

Ends is trying to have its cake and eat it, too. It wants to be a film about a serious topic that shows how domestic violence perpetuates, and how love and good intentions can blind us to red flags. But it ALSO wants to be a glamourous romance about a love triangle centered on a small-town girl with big-city dreams and the two dreamboats trying to win her heart. And it somehow wants to exit the first premise without the audience completely hating Ryle’s guts, so there is a third act reveal meant to make us understand him which no one ever needed to do. It’s also a visually messy film, with some confusingly shot sequences, particularly around violent incidents, and equally confusing editing that sometimes makes it hard to figure out where we are in the scene and what is happening. It doesn’t quite sink to the level of bland basic cable looks, but it’s close. It Ends With Us has lofty goals it ultimately cannot meet, and the end result is a bad film that is borderline insulting in its depiction of the very subject it seeks to explore.

It Ends With Us is now playing exclusively in theaters.

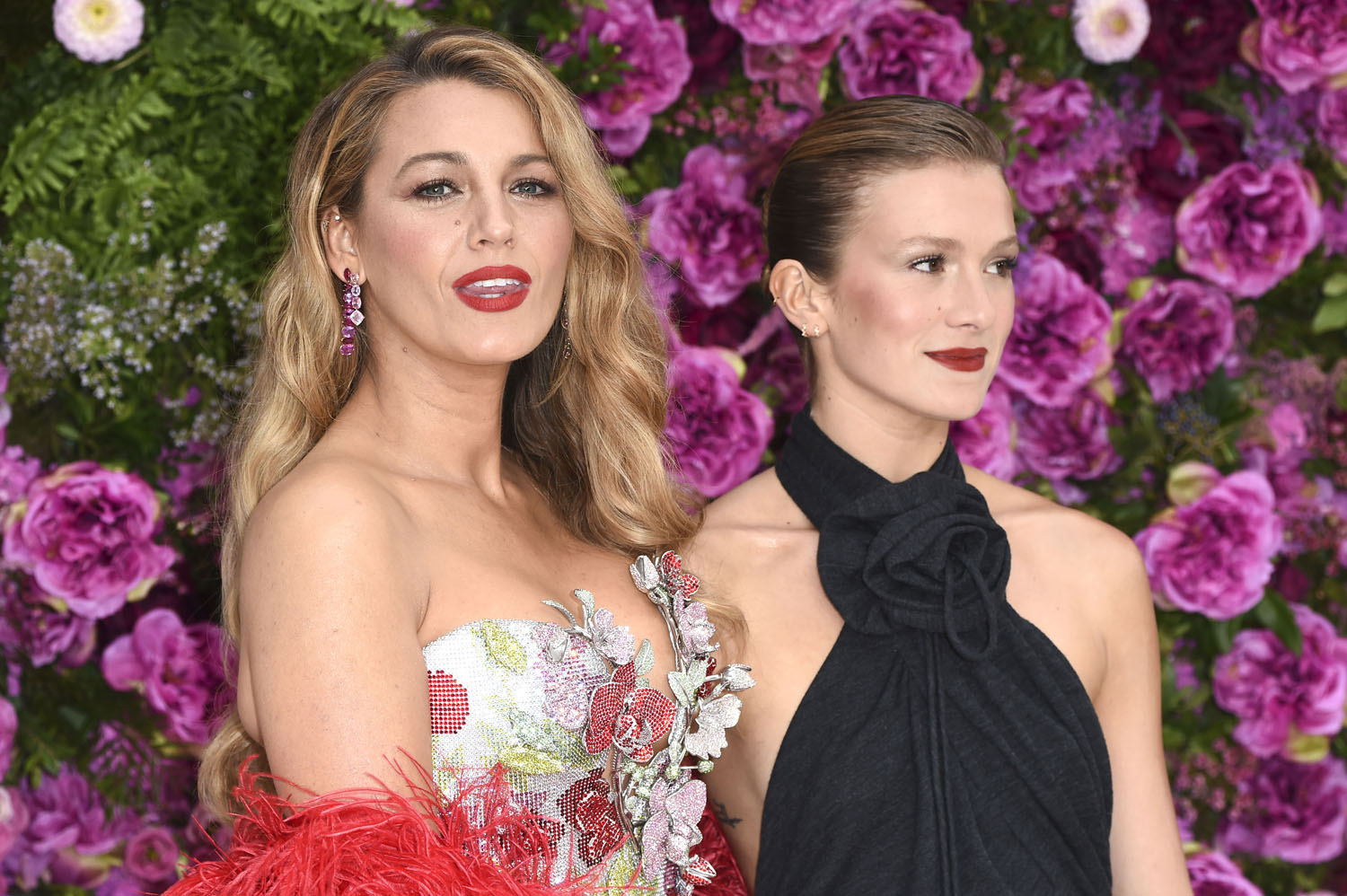

Attached - Blake Lively and Isabela Ferrer at the London premiere of It Ends With Us and Blake out in London to promote the film earlier in the day.