Kristen Stewart in Spencer: A Fox in a Trap

A spiritual sequel to Jackie, his 2016 biopic of Jacqueline Kennedy, Pablo Larraín’s Spencer is a portrait of a lady in distress, a biopic less interested in historicity than it is hysteria. Set over three days during the Christmas holiday at Sandringham, Spencer finds Princess Diana (Kristen Stewart) hanging on by a thread, hounded by the press, held apart by the public, abandoned by her husband, and scrutinized by royal minions that bring strict militaristic ideals to even the most mundane of family interactions. As in Jackie, Spencer is focused on a particular moment of extreme emotional duress meant to strip away the trappings of celebrity and privilege to reveal the raw human wounds beneath the façade, and there Larraín finds in Diana a dizzying and dizzied figure, tormented, seething, spinning between fantasy and reality, and clinging to whatever shreds of herself remain after a decade in the royal spotlight.

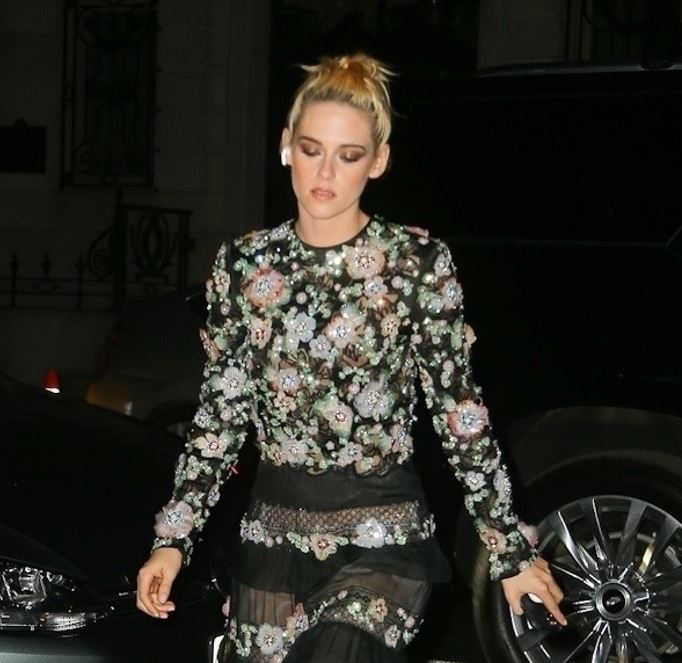

Kristen Stewart’s performance is less of an impression and more a suggestion of Diana; she inhabits not the memory of the real person but the collective, cultural memory of “Diana”, the winsome beauty who married a prince and delivered a fairytale to the masses, only to face crushing disappointment and humiliation once trapped in the castle. But she is also “Diana”, the clever, witty young woman who knows her angles and how to play to the public for maximum appeal. And she is “Diana” the doting mother, and “Diana” the woman scorned, and “Diana” who struggles with bulimia (content warning for on-screen depictions of eating disorders and suicidal ideation). Stewart captures all these facets and still makes her Diana feel not only true to the spirit of Princess Diana—if not to the letter of Diana’s law—but also like a pure invention of the fantasy of Spencer.

With a breathy voice that at once sounds nothing like Diana and still evokes her distinctive speech, Stewart plays Diana as a woman on the edge, at the end of her rope, and every other metaphor for just about done with this sh-t. Her marriage is over, Charles (Jack Farthing) so checked out he gives Diana and Camilla the same exact pearl necklace for Christmas, and she is barely going through the motions of maintaining royal protocol. Working from Steven Knight’s script, Larraín does an excellent job framing the ridiculous pomposity of royal tradition, including an introductory weigh-in that mandates Diana must sit on a scale as soon as she arrives at Sandringham for the decidedly unfestive festivities. For a woman in the throes of an eating disorder, what a nightmare, and how ragingly insensitive. It is later intimated that everyone knows about Diana’s bulimia, which makes the weigh-in even more callous and disturbing.

But this is the tone set by Larraín. Though there are some characters who express genuine, personal concern for Diana, such as her dresser, Maggie (Sally Hawkins), and the Sandringham chef, Darren (Sean Harris), no one can quite scale the walls of protocol to truly reach Diana. She reaches out, and sometimes there is someone to take her hand, but there is never anyone to hold on, to remain with her. She is constantly severed from any source of comfort—Maggie sent away, her sons occupied with strict timetables and predetermined activities, Darren unwilling to breach protocol no matter how much he seems to like Diana. And hovering over all is Major Gregory (Timothy Spall), an amalgamation that stands in for the “grey men” who dictate so much of royal life. He might actually be trying to help Diana, but his watchful eye and interference only serve to make her feel more caged, more persecuted. A biography of Anne Boleyn is taken as a warning, another royal wife unable to bend to protocol whose philandering husband had the power to remove her head. In the modern day, that particular fate won’t befall Diana, but she is haunted by the specter of death. Spencer is not overly macabre, but there is a pall hanging over Diana: she is that fox, caught in a trap, and her freedom is not guaranteed.

With flights of fancy such as meetings with the ghost of Anne Boleyn (Amy Manson), Spencer will challenge those looking for hagiography. It is an extrapolation of an idea, an imagining of, perhaps, Diana’s last Christmas at Sandringham, painting with a loose brush what it might have been like to be Diana, with a thousand years of history bearing down on her as her marriage falls apart. As Diana, Stewart sublimates her natural vulpine quality into something wilier and warier, not just a fox, but a fox caught in a trap, in pain, furious and frightened. Everyone treats her as if there is something wrong with her, as if she is weak and needs constant minding. But an animal that gnaws its leg off to escape a trap is not weak. It is only desperate, and in that desperation finds perhaps the greatest strength of all—the strength to suffer to survive, to have freedom at all costs. And there is Diana, gnawing, gnawing, gnawing.

Spencer is now in theaters.