Robert Pattinson in The Batman

It’s a familiar scene: a city with a skyline somewhere between Gothic and Art Deco, deep in night, or glimpsed through rain, or seen in the half-light of the dying day, dirty, overcrowded, downtrodden. The people: edgy, tense, and keeping to themselves. A good man: alone, the final bulwark against all-out corruption and evil. The shadows: creeping outward, harbingers of even worse things to come. Matt Reeves’ The Batman, as the kids say, “understands the assignment”. Here is a Gotham City built out of scraps of the Gothams that came before yet looks wholly new in its style of grime. It is also a city that looks lived in, with new architecture built over old, and urban blight a creeping disease that is eating the city from within by degrees. And here is a vision of Batman that, even among a well-developed cinematic history, stands apart as the most mythic and otherworldly Batman we’ve yet seen. This is Batman as a back-alley war god, a scarred and scarring figure who wields fear as his first line of defense—a Batman built for shock and awe.

And this is a Batman who doesn’t delineate between his two halves. Bruce Wayne (played by a SPECTACULAR Robert Pattinson) is deep in his trauma, unhealed and uncaring, devoted solely to his nighttime activities. It’s year two of Batman’s reign in Gotham, and he’s still figuring things out. Not all of his gadgets work perfectly, the Batmobile is a little unreliable, and while he’s made an ally of Jim Gordon (Jeffrey Wright), the Gotham City police distrust and loathe him, for he is a symbol of their utter failure, and the public fears him as just another element of the decay devouring Gotham from within.

The DC pantheon of heroes has always had a uniquely mythic proportion, and writer/director Reeves (who co-wrote the script with Peter Craig), and Pattinson imbue this Batman with that mythic edge. They don’t try to pretend for even one second that Bruce Wayne is a normal person and can exist in a normal life, he has no cover persona and is not interested in a life beyond his crusade. He’s deeply weird, isolated, and made awkward by wealth and loneliness, consumed by unexpressed anger and grief, a furious god looking down on a realm he can never fully occupy or understand.

Visually, The Batman is rife with the “typical” Batman elements—the dying city, the false glamor of a nightclub, the cages within cages of a police station, a natural world just beyond the border waiting to reclaim it all—but The Batman is also loaded with mythical references. Bruce Wayne lives in a tower perched over the heart of the city, a literal Mount Olympus; that nightclub contains secret sub-levels of depravity, a Hades from which only the likes of a hardened, bitter Selina Kyle (Zoe Kravitz) can escape. The mythological allegory of climb and descent matters in The Batman, as Batman goes up, up, ever way from the everyday folk of Gotham he nominally protects, only to descend when the latent compassion that is his only separation from the criminals he pursues stirs him into higher action. There are images in The Batman (lensed by Greig Fraser) that take on the majesty of such a mythological read on a well-worn character, and this film, like the best classical paintings, understands the impact of bright things emanating from the darkness.

Michael Giacchino’s score, too, enhances the odd stateliness Pattinson brings to Batman. This Batman lurks, he looms, he slides by in the periphery, an incongruous figure everywhere he goes, at home nowhere in the mortal realm he graces. Giacchino’s score starts with a spaghetti Western twang that situates Batman in a long line of outsider gunslingers come to settle a score but builds with an orchestral intensity better suited to religious sacrament (indeed, Ave Maria, a prayer for mercy, winds in and out of the original music at key points). The only complaint is that the score is a bit aggressive, especially in the early going it feels like Reeves & Co. don’t quite trust the audience to buy into this rather disorienting Batman and leans on the score and voiceover to make sure we “get it”.

But we do get it, because this Batman, striking, strange, stately, falls in line with thousands of years of storytelling about gods and monsters. He’s cruel Ares, softened only by the love of a woman he can’t hold, and, sometimes, half-formed affection for a mortal favorite. He’s not complicated, he’s very clear from the first moment he appears, that back-alley god matched against a trickster doing what all tricksters do—expose hypocrites and the rot at the heart of the god’s doomed world. And Batman will only succeed if he learns the lesson all just gods must: that it is not enough to fight in the city below his isolated aerie, he must fight for it.

No superhero film has ever done gods and monsters as well as The Batman, yet for all the grandiosity of staging and performance, The Batman is a relatively grounded tale about grief and revenge with a side of colorful characters and souped-up gadgets and an actual, honest-to-goddess detective story. But as intimate as The Batman feels at times, there is always this outsize proportion of mythic grandeur around the edges that makes the whole thing feel like a story being told in a cave as shadows dance across the rocks. Gotham is a real place and no place, Selina Kyle is a thief and a fury, Batman is a vigilante and a vicious god, everything echoes with the doubled resonance of the best myths, at once a thrilling adventure and a cautionary tale. But who is being cautioned? The people, turning away from the corruption before them? The god consumed with vengeance? Or the good man, reaching into the dark with a desperate hand, searching for anyone—anything—to reach back?

The Batman is exclusively in theaters from March 4, 2022.

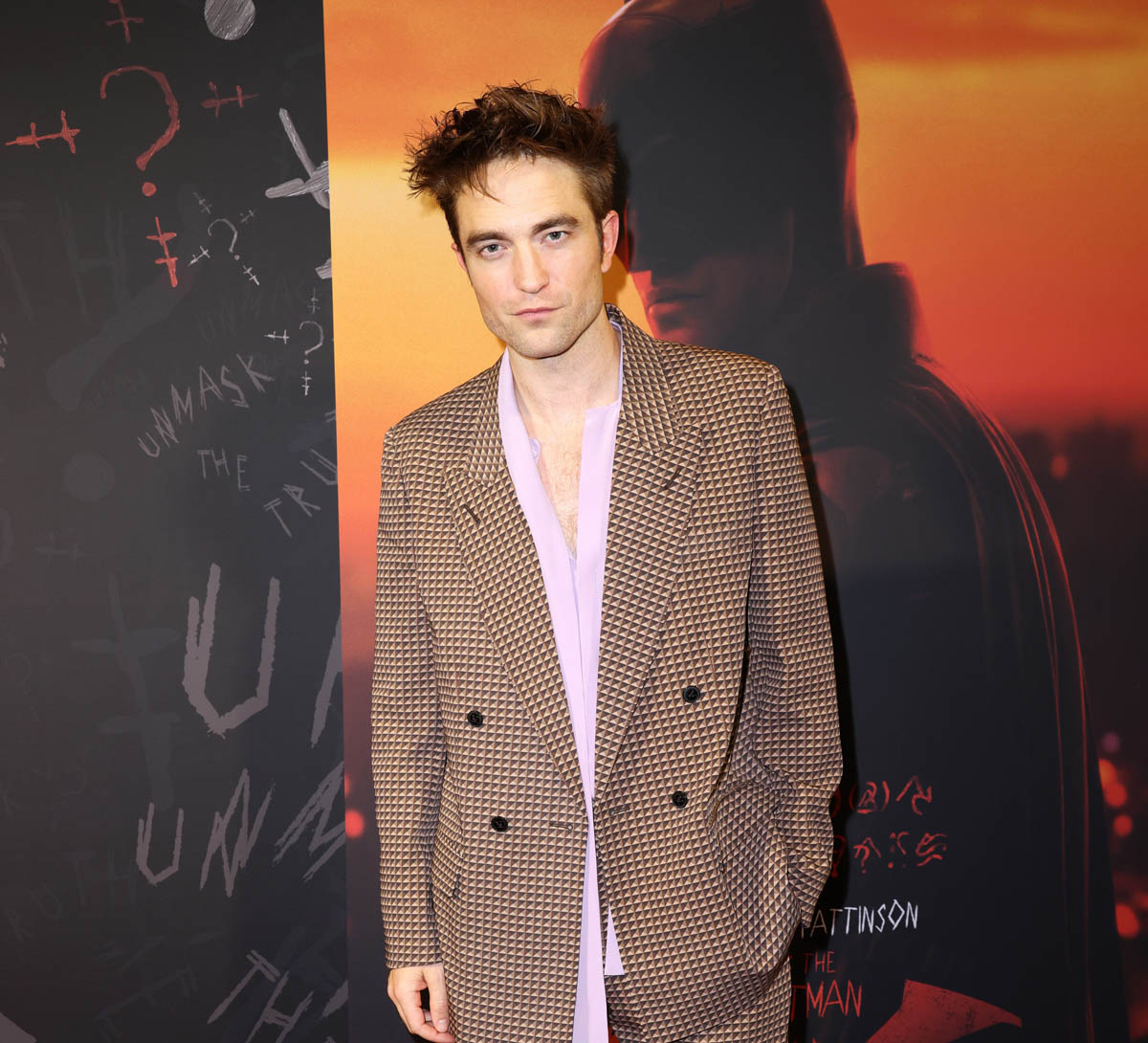

Attached - Pattinson at a special screening of The Batman in Miami the other day.