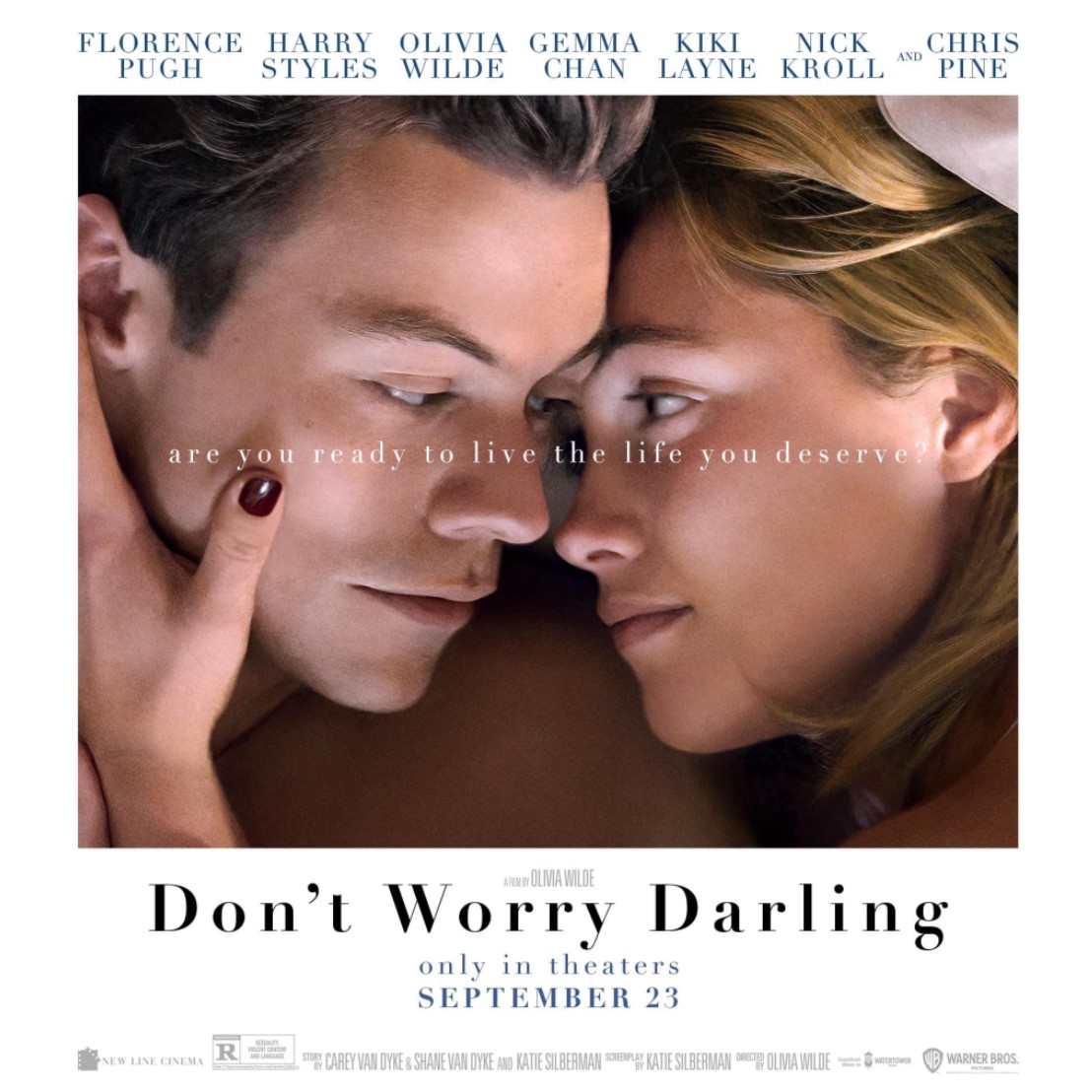

Miss Flo in Don’t Worry Darling

Spoilers

After much sturm und drang, Don’t Worry Darling is finally here, missing comma and all, and it’s…fine. 100% middle of the road movie. It’s the kind of film you’d find flipping through channels on cable on a lazy weekend afternoon and settle in to watch, except no one has cable anymore. Olivia Wilde’s sophomore effort as a director is a mixed bag, and while she shows the same command of scene and style she demonstrated in Booksmart, here she shows an inability to overcome a weak script—or maybe a complicity in telling an oversimplified story. Don’t Worry Darling is slick and stylish and mostly well-acted, but it is hamstrung by a cliched concept and dumbed-down story. With more willingness to plumb the depths of human frailties and weakness, Darling might have been a twenty-first century Gattaca, combining style and smarts to tell a story that tests the limits of technological possibility and moral fortitude. Instead, Darling settles for morality police-proofing one of speculative fiction’s oldest yarns.

Alice (Florence Pugh) is a young wife in a thriving marriage. Her husband, Jack (Harry Styles), works for the “Victory Project”, a mysterious organization in the desert with Manhattan Project vibes. Jack is doing Something Important For The Future, while Alice keeps house and swans around with the other neighborhood housewives. It’s the 1950s, every home is immaculate, every woman dressed to the nines and fully made up at every hour of every day. Alice is proud of Jack and so in love she attempts to delay him leaving for work, they enjoy a healthy sex life and robust social calendar. Everything is perfect.

Of course, it isn’t, everyone knows that from the moment the film begins. It’s impossible to discuss the failings of Darling without spoiling the ending, so this is your last chance to check out.

After witnessing a plane crash while on the bus one day, Alice stumbles upon the Victory Project headquarters and touches a mirrored window. After that, she begins to have “hallucinations” that eventually reveal she is trapped in a simulation. Victory is a Stepford scenario, where weak men have trapped their wives in a Fifties fantasy where the Men Are Men and the women vacuum and drink martinis all day. The leader of the project, Frank (Chris Pine), is, in the real world, an incel-ish online “thought leader” who invented the Victory Project as a way for men to reclaim their place in the social order. Jack is, in fact, out of work in the real world, where Alice is a surgeon struggling to support them both. Their marriage isn’t thriving, it’s failing, and kidnapping Alice and forcibly inserting her into the Victory simulation is Jack’s way of clinging to their relationship.

In a better movie, Victory and its implications would be subtler, with more complexity in the range of people present within the simulation. It is intimated that Bunny (Olivia Wilde), a fellow housewife, knows the truth and chooses to stay in Victory after the deaths of her children in the real world. Here, at least, she can be a mother to “living” children. Darling needs more Bunnys, more people who complicate the theory. It needs subtlety and nuance, and a better representation of different reasons someone, even women—especially women—might choose to live in a trad wife fantasy as opposed to the more difficult, demanding real world. But Darling is so simple as to be borderline stupid, its message and morality clearly spelled out, as if those making the film (it was written by Carey and Shayne Van Dyke, with a substantial overhaul by Katie Silberman, Wilde’s Booksmart collaborator) are afraid of their message being misinterpreted.

In Booksmart, the girls are allowed to be messy and emotional and mean and bad friends and imperfect. In Darling, though, the women are almost all victims, allowed no agency or expression beyond one character, Margaret (Kiki Layne), taking drastic action after discovering the same truth as Alice. Darling wants to say big things about misogyny and systems of control and how patriarchal structures inhibit and abuse women, but it also wants to have “empowering” sex scenes in which Jack goes down on Alice—Alice, who is his victim and an unwilling participant in his fantasy. The sex is ultimately non-consensual, but the film never wrangles with that implication once Alice discovers her true reality.

Darling looks great. The midcentury aesthetic is flawless, with costume design by Arianne Phillips, production design by Katie Byron, art direction from Mary Florence Brown and Erika Toth, and set decoration by Rachel Ferrara. Wilde’s direction is smooth and stylish to match the visuals, lensed by cinematographer Matthew Libatique. And the acting is mostly good, especially from Pugh and Pine, the most electric scene in the film is their clash at a dinner party, though Styles is, once again, outmatched by better actors around him, and his accent is weird and distracting. But on the whole, the individual elements, especially anything visual-related, are good-to-great. The story is just so simple, so infantile, it undercuts the whole effort. It’s insulting to the audience, who can handle complexity and imperfection in characters, and wastes all that good craft on a dumb story. Patriarchy bad, says Don’t Worry Darling. But then, why do so many women remain enthralled by its promise? The worried darlings have no answer.

Don’t Worry Darling is now worrying darlings in theaters worldwide.