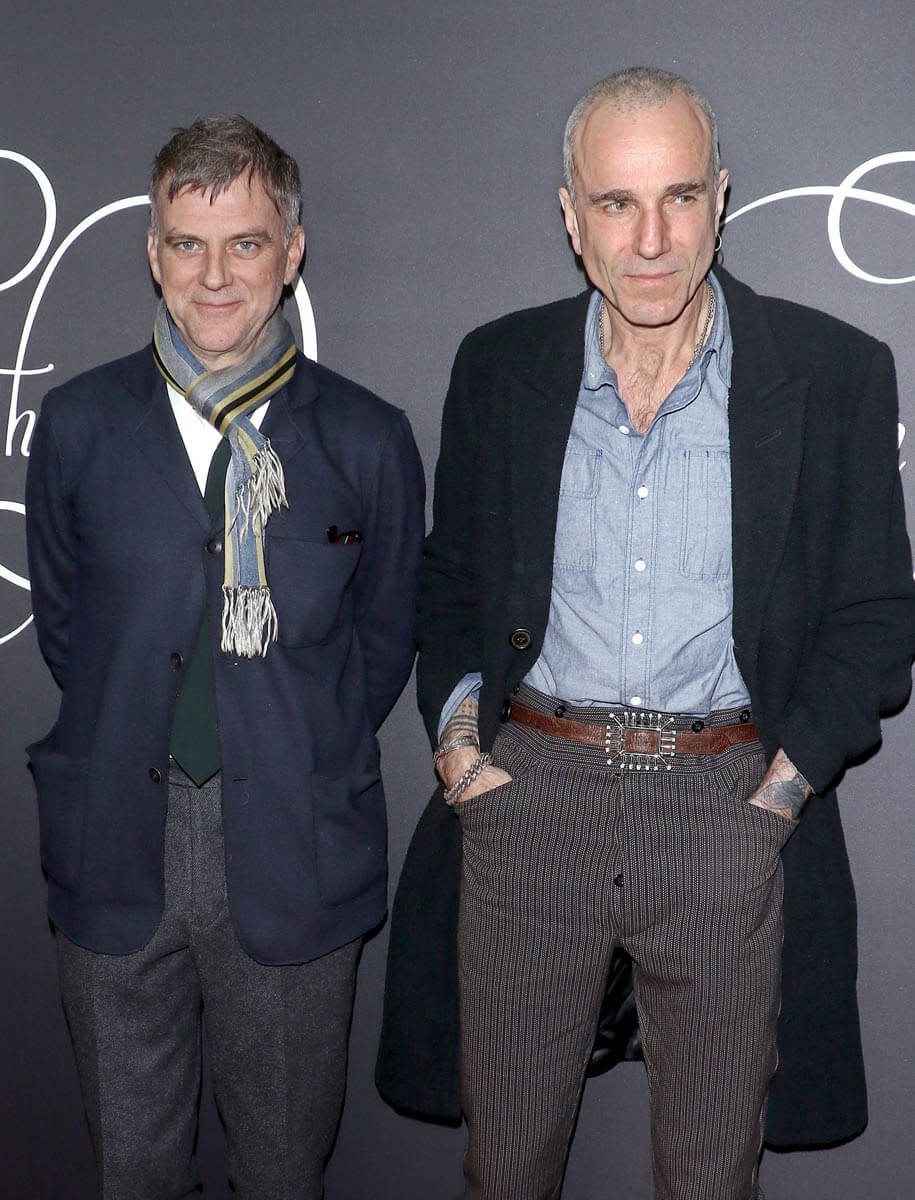

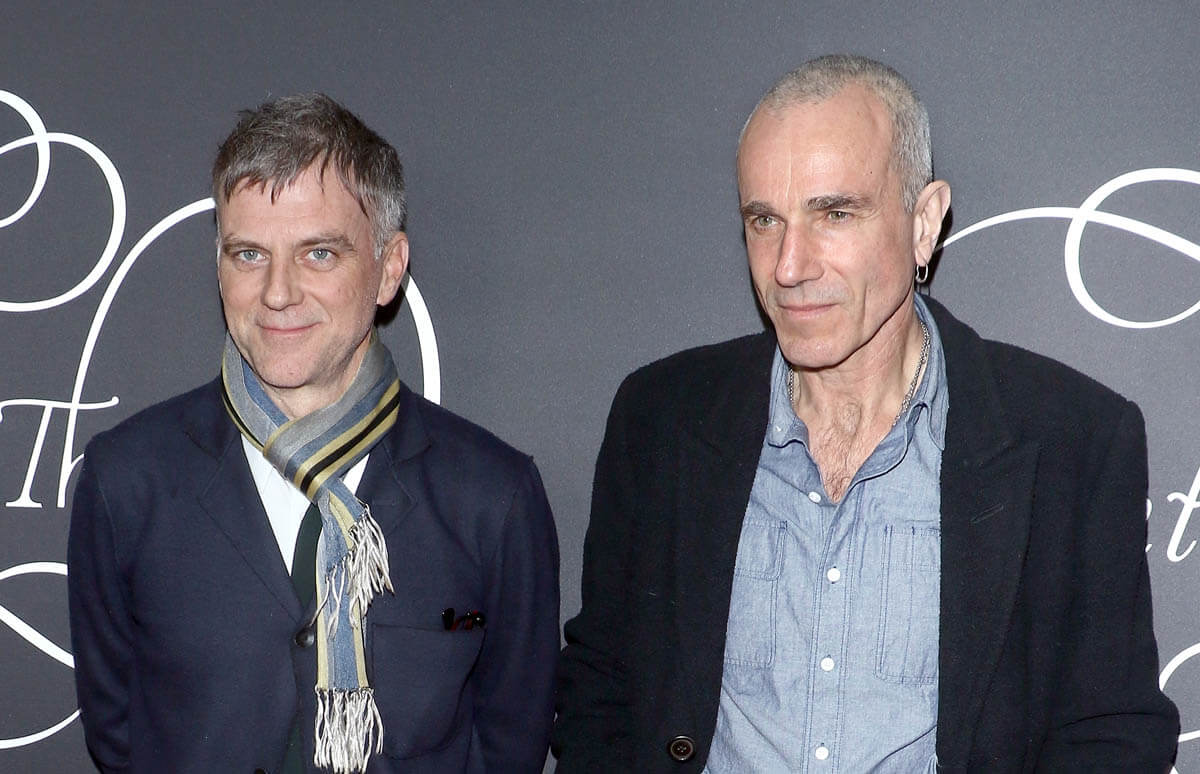

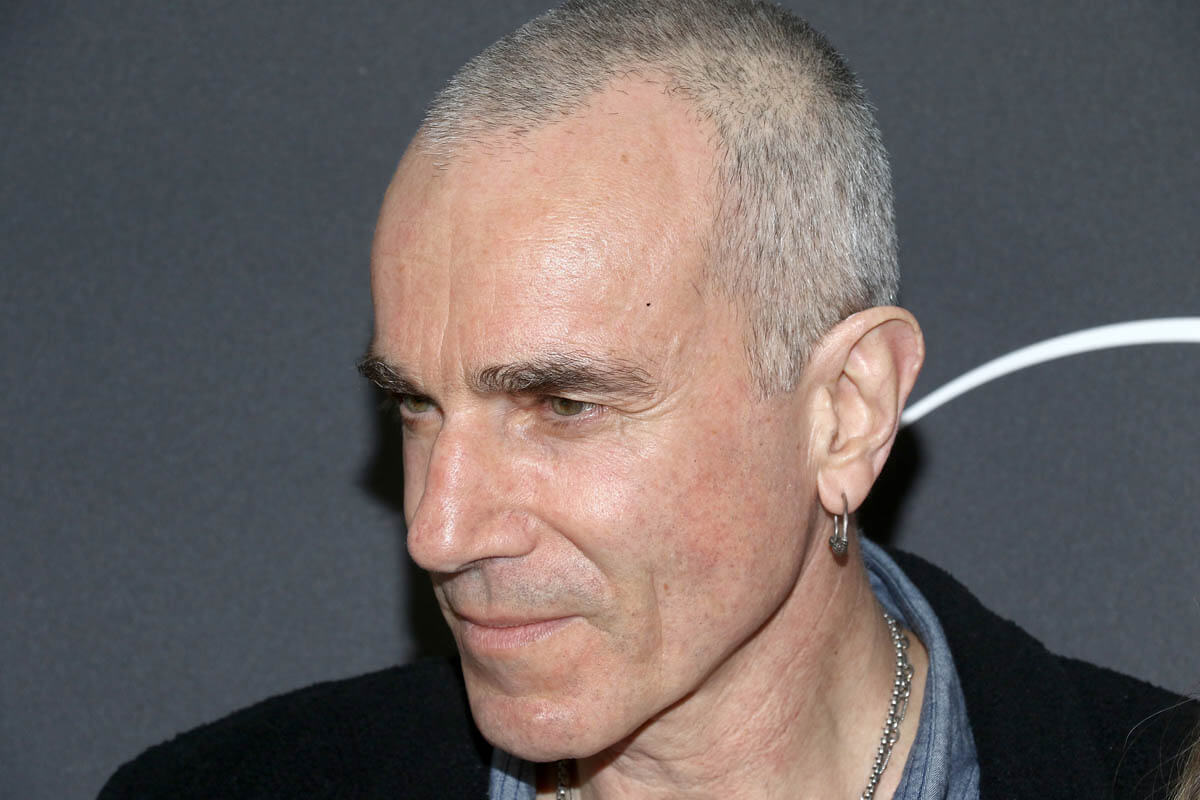

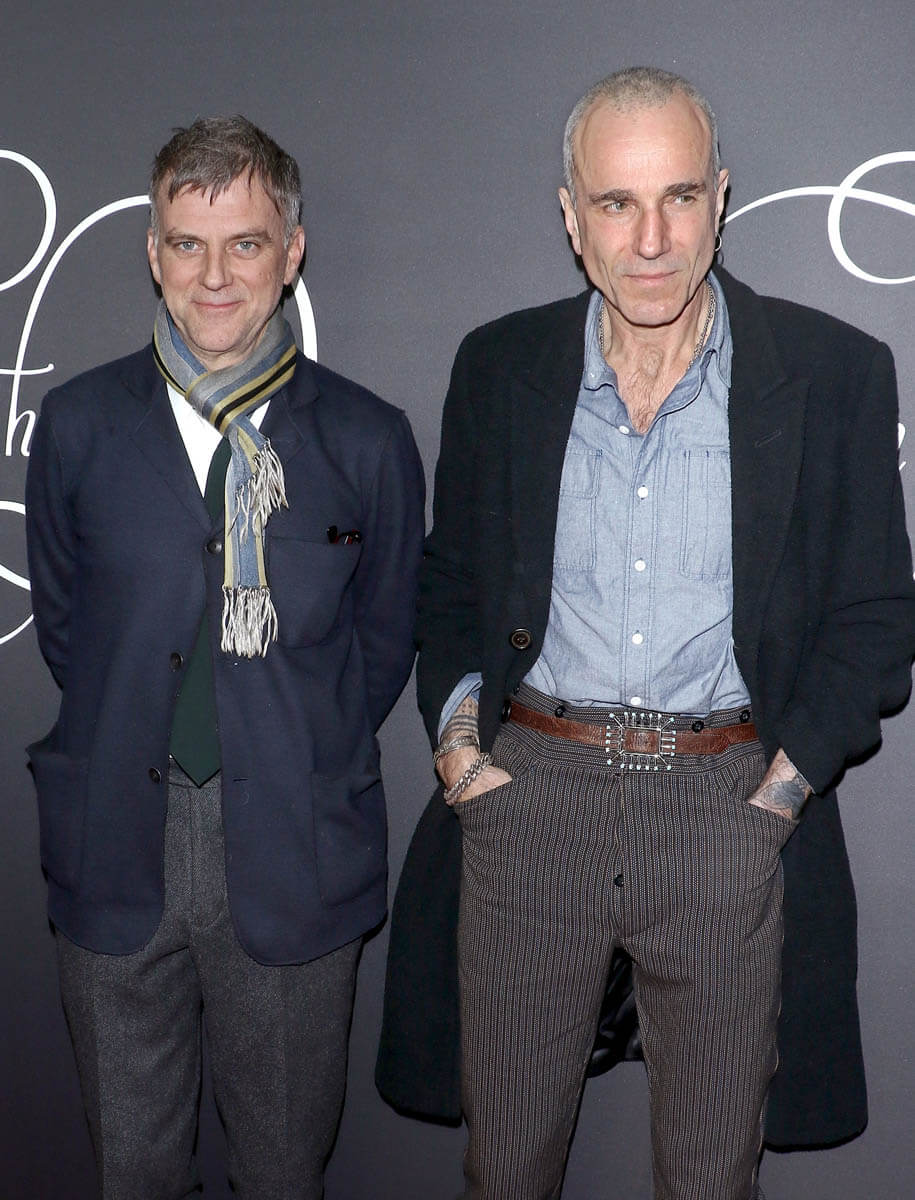

Daniel Day-Lewis (maybe) goes out on a high note

In a career littered with great performances, it’s not hard to see why Daniel Day-Lewis would choose Phantom Thread’s Reynolds Woodcock to be his final performance (for now). For one thing, he looks like himself. There’s no facial hair or affected gait or prosthetics or other device to obscure him from the audience. There’s something romantic about such a dedicated chameleon choosing to go out as more or less himself, and it makes his performance all the more remarkable because he ISN’T hiding, and yet, Reynolds Woodcock is as indelible as Daniel Plainview, Bill the Butcher, Hawkeye (champion of the Colonial Biathlon), Christy Brown, Newland Archer, or Danny Flynn.

Reynolds Woodcock is an affirmation: Daniel Day-Lewis doesn’t need tricks. (He does, however, continue to prepare his ass off, and one of the most annoying things about the Method-ization of acting is confusing preparation for practice.) He’s Oscar-bound, of course. Even if Reynolds Woodcock didn’t have the shine of being Day-Lewis’s (potential) final performance, it’s worthy work. The only question is whether or not he wins his fourth Oscar, putting him onto the plane occupied only by Katherine Hepburn as a four-time winner (thought momentum is still with Gary Oldman.)

Reynolds is a man of precision and control, master of his domain and at the pinnacle of his field. He’s a couturier, clearly inspired by the likes of Norman Hartnell and Charles James, a designer who makes custom dresses for clients of the upper crust, with movie stars, countesses, and princesses traipsing into his atelier for gowns that give them “courage” or realize a fantasy. He rails against “chic”—a new concept drifting in from the continental House of Dior—and leaves his sister to jettison his model-muses when he tires of them. He’s an artist, a genius, and an asshole, and Day-Lewis plays him with the straight-ahead focus of like recognizing like.

Phantom Thread is a work of tremendous focus, not only from Day-Lewis but also Paul Thomas Anderson, who writes, directs and shoots the film (albeit uncredited as the cinematographer). Phantom Thread moves with an exquisite subtlety, the result of Anderson’s total control of the frame, and assisted by the precise editing of regular collaborator Dylan Tichenor (who also edited The Assassination of Jesse James, another film that moves with a specific rhythm). Everything about Thread is exquisite, from the sets—London’s Fitzroy Square provides a gorgeous Georgian backdrop—to the stunning parade of gowns that comes out of Woodcock’s atelier, courtesy another Anderson regular, Mark Bridges. Johnny Greenwood’s score is lushly orchestral, although we’re probably in for another round of “Is this eligible?” because there are recognizable themes scattered throughout the score, including music from Hector Berlioz (There Will Be Blood was ruled ineligible for using too much previously written material).

The actors match Anderson’s focus, too. Besides Day-Lewis, Lesley Manville gives a razor-sharp performance as Woodcock’s sister, Cyril, who keeps his business and personal life running. And breakout Vicky Krieps as Alma goes toe-to-toe with Day-Lewis and doesn’t wither in his shadow. Alma is simple but smart, recognizing what she wants from Woodcock and the lengths she must go to in order to secure it. The give and take between Reynolds and Alma is a delicious, slow torture, almost prudish in its chasteness—sex is a Hayes Code-style hint and nothing more—but their relationship throbs with tension and desire and loathing. Power is their language, affection merely a byproduct to be tolerated amidst their struggle for control. Innocent, wide-eyed Alma appeals initially because she is nothing and Woodcock can make her everything, but Alma is as devious as Reynolds is cruel, and their love is warped and knotty, as suits two peculiar deviants.

Phantom Thread is a sumptuous aesthetic experience full of masterful performances and craft, orchestrated by a master filmmaker. It’s not going to be for everyone because PT Anderson films are never for everyone. But if you can surrender to the way Anderson tells a story, this is a delightful, sly treat, a cinematic bon bon of malcontented lust and power twisted into a perverted romance.