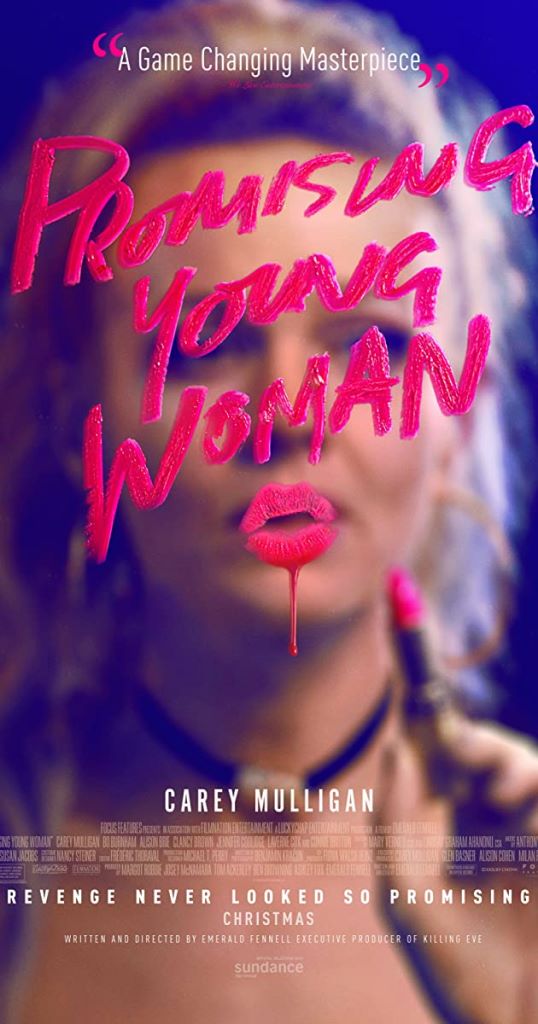

Carey Mulligan in Promising Young Woman

Promising Young Woman is a gleaming, glittering cinematic candy hiding a poisonous center, something sweet on the surface with a vicious sting that will ruin your night for sure. Emerald Fennell, in her feature directorial debut, has lovingly crafted a delicious cinematic treat meant to make your stomach turn. The film centers on Cassie (a career-best Carey Mulligan), a 30-year-old medical school drop-out still living with her parents and working at a local coffee shop. Her manager-cum-friend, Gail (Laverne Cox), is pushing her to apply for a managerial position, and her parents (Clancy Brown and Jennifer Coolidge) are sending not-so-subtle hints they’d like Cassie to move out already. But Cassie prefers her coffee-counter job and her childhood bedroom in her parents frozen-in-time house. She spends her days reading and snapping “no” at customers (MY HERO), and her nights pretending to be drunk in clubs to lure men into taking her home, where she busts them for attempting to assault a drunk woman. She’s a self-styled vigilante, teaching men one at a time not to prey on incapacitated women, although there is a legitimate question about how effective she really is.

Fennell approaches the early portion of the film with her tongue planted firmly in her cheek. A scene at a club photographs men on the dance floor the way hot girls are usually shot, the men’s khaki-clad butts gyrating awkwardly, their doughy middles barely contained in ill-fitting button downs the subject of lingering camera angles. It is so unsexy and ridiculous, and while it is on-the-nose, it doesn’t make Fennell’s point any less salient—the way women are photographed in these kinds of club scenes IS ridiculous and dehumanizing, and simply replacing scantily-clad women with business-cazh men reveals how stupid this cliché really is. This same dark, bone dry humor applies to the scenes of Cassie confronting the “nice guys” who set out to “help” her only to try and take her underwear off once they think she’s passed out. The flopsweat desperation of these men is palpable, and their obvious fear at being harmed is rich, given what they were about to do to Cassie.

It is clear Something Bad has happened to Cassie, that she is stuck in a kind of arrested development. When Ryan (Bo Burnham), a cute former classmate, comes back into her life, we learn what that thing is: Cassie’s best friend, Nina, was sexually assaulted at a campus party, and ultimately died by suicide. Not only is Cassie grieving, she is infected with a kind of survivor’s guilt, since she did not go to the party where Nina was assaulted. Her vigilante club act is Cassie’s way of “saving” Nina, at least until Ryan makes known that Cassie’s former classmates, including the people who hurt Nina, are all thriving. It is simply too much to be borne. Cassie cannot move on, she cannot let Nina go, and she is clearly SEETHING with rage at the way Nina was treated as a victim of intimate violence. From this point, Woman shifts gears into something darker, sharper, more ambitious and grander than it seems at first.

Fennell takes deadly aim at rape culture, targeting everyone from the assailant to the classmates who didn’t believe Nina, to the institution that valued a promising young man’s future over a promising young woman’s safety. Woman highlights the f-cked-up-ness of a culture that positions women seeking justice as an inherent attack on men, turning the tables on victims and making them the aggressor while the men who harmed them become the aggrieved party—become the victim with whom everyone sympathizes. One person involved in Nina’s case back in the day has since had a moral awakening and regrets his part in it, and this is called a “psychotic break” by others, which says everything about how our culture views the industry that thrives around protecting men from the women who accuse them.

In the final act, Woman veers sharply from where you think it’s going to go, and for many people, the ending simply won’t work. I love the ending, though, because it fits with the infernal engine at the heart of Fennell’s story. Cassie is a spark, a hot spot that can singe if you get too close, and Ryan and his yearbook updates are gasoline thrown on that spark. Over time, Cassie’s rage has dimmed, she has sublimated most of it into her nighttime activities and clinging to the childhood she shared with Nina. But once she is reignited, she blazes out of control, and she does what all infernos do: she scorches everything around her, including any chance of this film having a traditionally satisfying ending. Some will love the tart bite and revel in the deliciously searing pain of it, while others will loathe the bitterness and acid after-taste. With its teen dream palette of electrified pinks and blues and bubblegum-pop soundtrack glossing over a black heart of festering feminine rage, Promising Young Woman is a nightmare dressed like a daydream.

Promising Young Woman will be in theaters on December 25 and will be available to stream at a later date.