Michael B. Jordan in Sinners

Growing up in the American South, something I find missing in most Southern-flavored media is the heaviness of the air. It is challenging to communicate in removed mediums like cinema because the viewer can never physically feel the weight of the air pressing down on them, so the burden is placed on the filmmakers to communicate something like that feeling. The way the air pushes down on you like a hand holding you back, the way it clogs your throat like wet cotton, the smell of it branding your nostrils—fecund, fetid, the dirt of dead and slithering things that grows only poisoned fruits. Vine-ripe berries burst with flavor but leave unmistakable stains on lips and teeth; everything that hot, sweaty, unbearable air touches is marked for life. You can leave the South, but it never leaves you, its stickiness imprinted on your skin forever.

Ryan Coogler’s Sinners is a Southern Gothic horror tale steeped in that stickiness, sweaty with need and desire, stinking of generations of rot just under the surface. Set at the tail end of Prohibition, Michael B. Jordan gives a dual performance as twin brothers Smoke and Stack, returning to the Mississippi Delta after years away—first at war, then working as bootleggers for Al Capone in Chicago. They are returning home as, they think, conquering heroes, with cash enough and beer enough to fund a juke joint that will offer their community a space safe from the ever-present threats of the Jim Crow South.

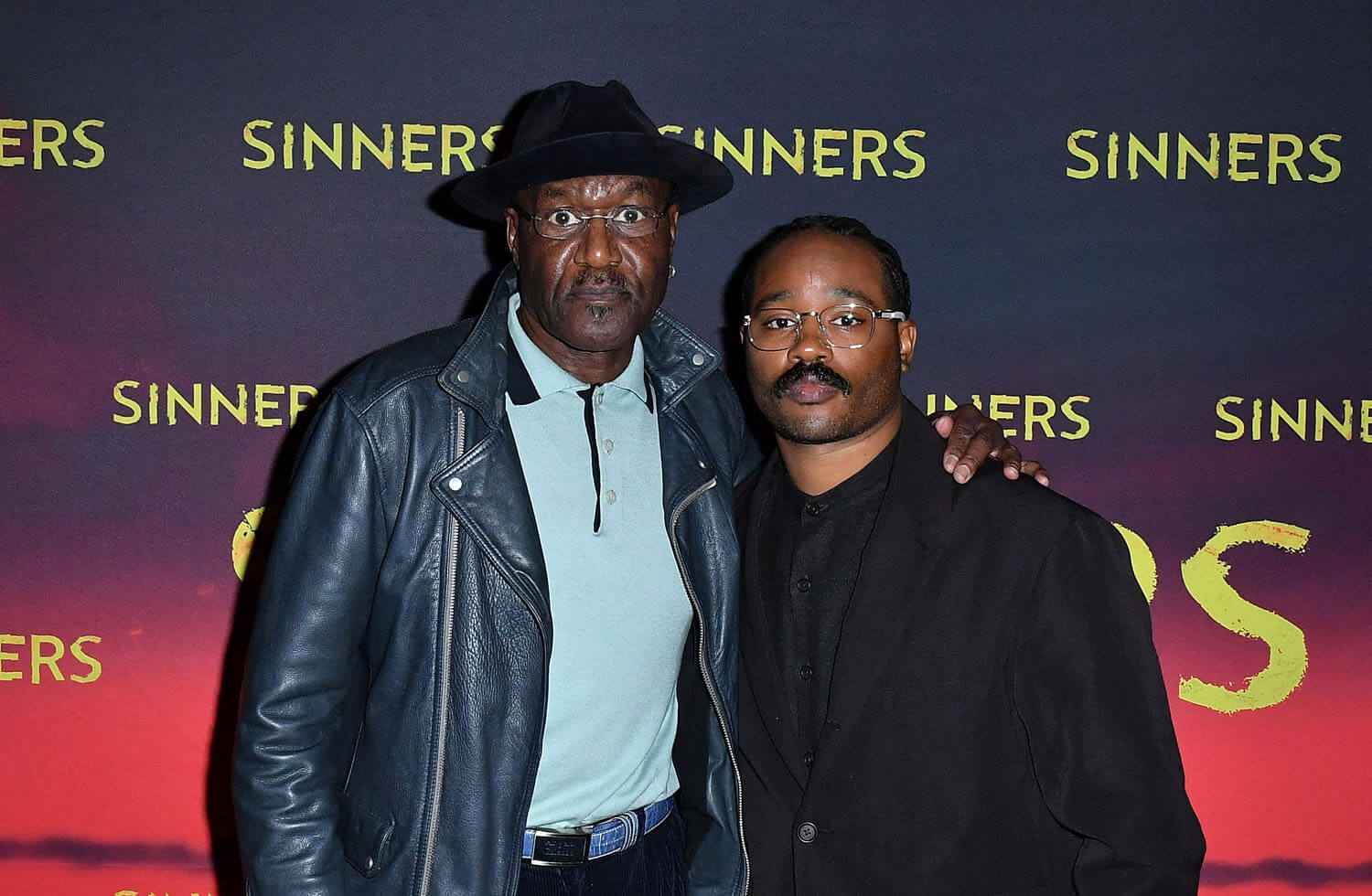

To that end, they buy a disused sawmill from local racist Hogwood (David Maldonado), and hire a bluesman, Delta Slim (Delroy Lindo, at his slick and charming best) to provide the music. There are also Smoke and Stack’s cousin Sammie (Miles Caton), a gifted young musician whose pastor father warns against blues music as a supernatural threat; as well as Stack’s white-passing former lover Mary (Hailee Steinfeld); and Smoke’s estranged wife, Annie (Wunmi Mosaku in yet another should-be breakout role), who agrees to cook for them. Annie is a Hoodoo practitioner who believes her practices kept the twins safe during their years in Chicago, though she could not save her and Smoke’s baby daughter.

Sinners soaks in a feeling of inescapable humidity, it is so hot and sweaty that heat waves practically roll off the screen, but it is also a film brimming with desire. Michael B. Jordan gets to play two romantic archetypes, the good boy and the bad boy, and he swaggers through both roles with ample charm and sex appeal. He has never looked handsomer, photographed and lit lovingly by long-time collaborator Coogler, working with cinematographer Autumn Durald Arkapaw. Jordan oozes sex from every pore and through every frame, and the heaviness of the air fills the film with the skin-tingling electricity of storm ripe skies and the inherent sexiness of wanting. Sinners is gravid with want—want of freedom, want of money, want of music, want of flesh.

The want of flesh is literal as a vampire arrives on the scene in the form of Remmick (Jack O’Connell), who promptly begins turning the locals, including Mary. Coogler ditches the modern soft romantic vampire for a style that calls back to the cinematic vampires of the 80s in films such as Fright Night, The Lost Boys, and Near Dark. Remmick is a compelling but innately threatening outsider, an imbalance in nature that must be corrected. Soon enough, opening night at the juke joint turns into a vampire vs. human bloodbath, and because this is the South, the Klan shows up, too. The twins’ attempt to create a space for Blackness to thrive was doomed from the start, with or without a supernatural threat. Hogwood and his Klan cronies were never going to allow the twins, or the local Black community, to flourish.

Thematically Coogler, who also wrote the script, swings for the fences. Vampires, Southern Gothic horror, the Prohibition setting, all of it builds an allegory for Black success amidst white capitalism, and how essentially impossible that is (though there is another supernatural flourish that suggests music, or in a broader sense creativity itself, as a path to Black liberation from white capitalistic control). It doesn’t one hundred percent work all the way through, the thematic purpose falters in places and the edges don’t completely line up narratively, but the attempt is so ambitious and the execution so superb—the craft of Sinners is EXCELLENT—that even with a slightly imperfect conclusion it is still better than any other film viewed so far this year.

Sinners is thoughtful and wildly entertaining, sexy and haunting, gory and thrilling, lively and whimsical. It takes its sweet time to get where it’s going, but when it arrives at its biggest moments, the film delivers on spectacle of sweeping scale. The scope of Sinners is breathtaking, in both a cinematic and thematic sense, and it is electrifying to watch a film try Big Things and do them well. Coogler has never been more in command of what his specific talents can bring to bear in a film and a story, from the intimacy of character interactions to the breathlessness of visually stunning sequences that literally transcend time and space. And all of it is bound by the feeling of choking on damp, heavy air, of oppression so innate it seeks to stunt all possible growth.

Sinners leaves an impression of stickiness on the skin, music humming in your bones, and Big Ideas stirring in your mind.

Sinners is now playing exclusively in theaters.