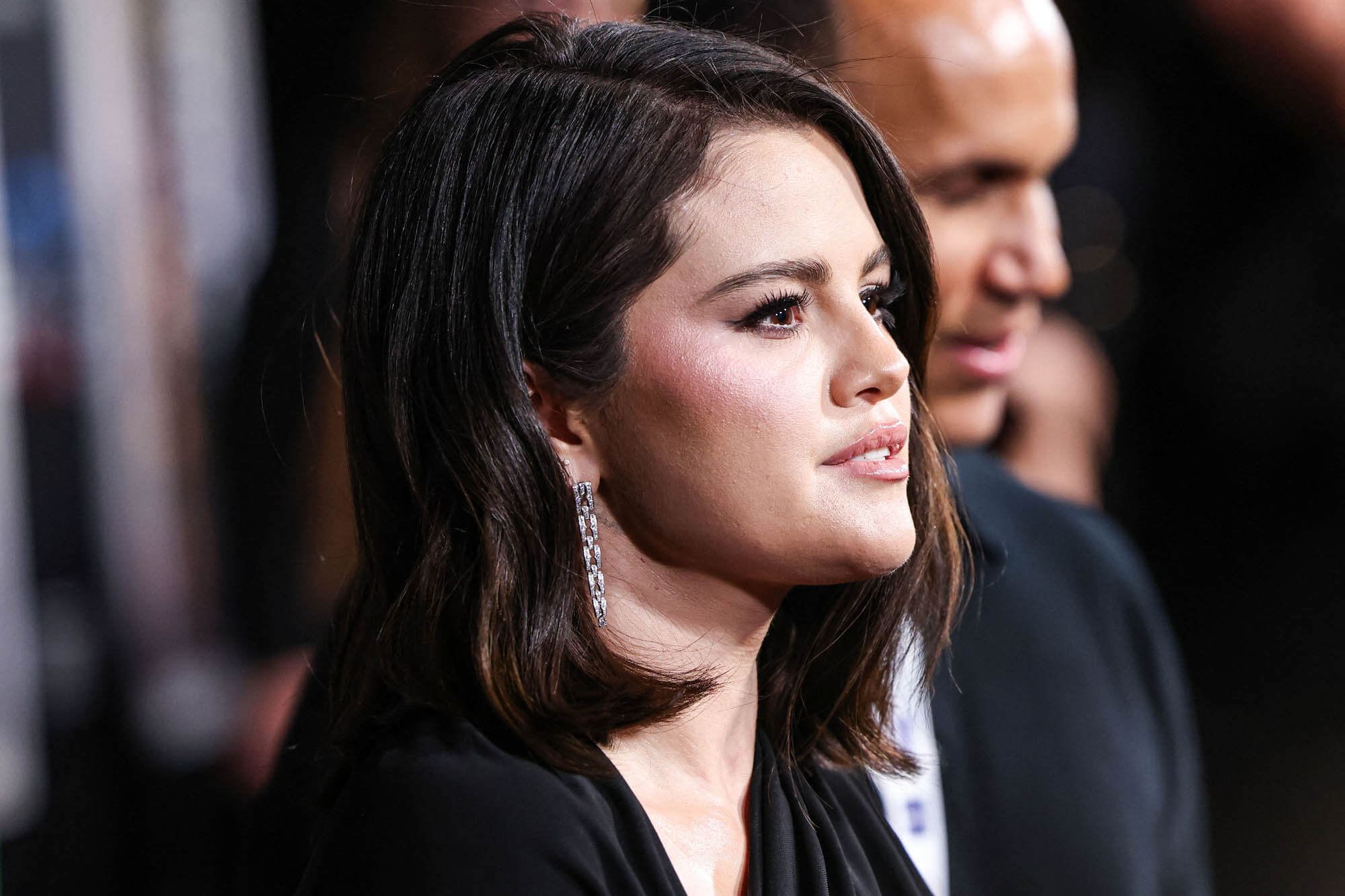

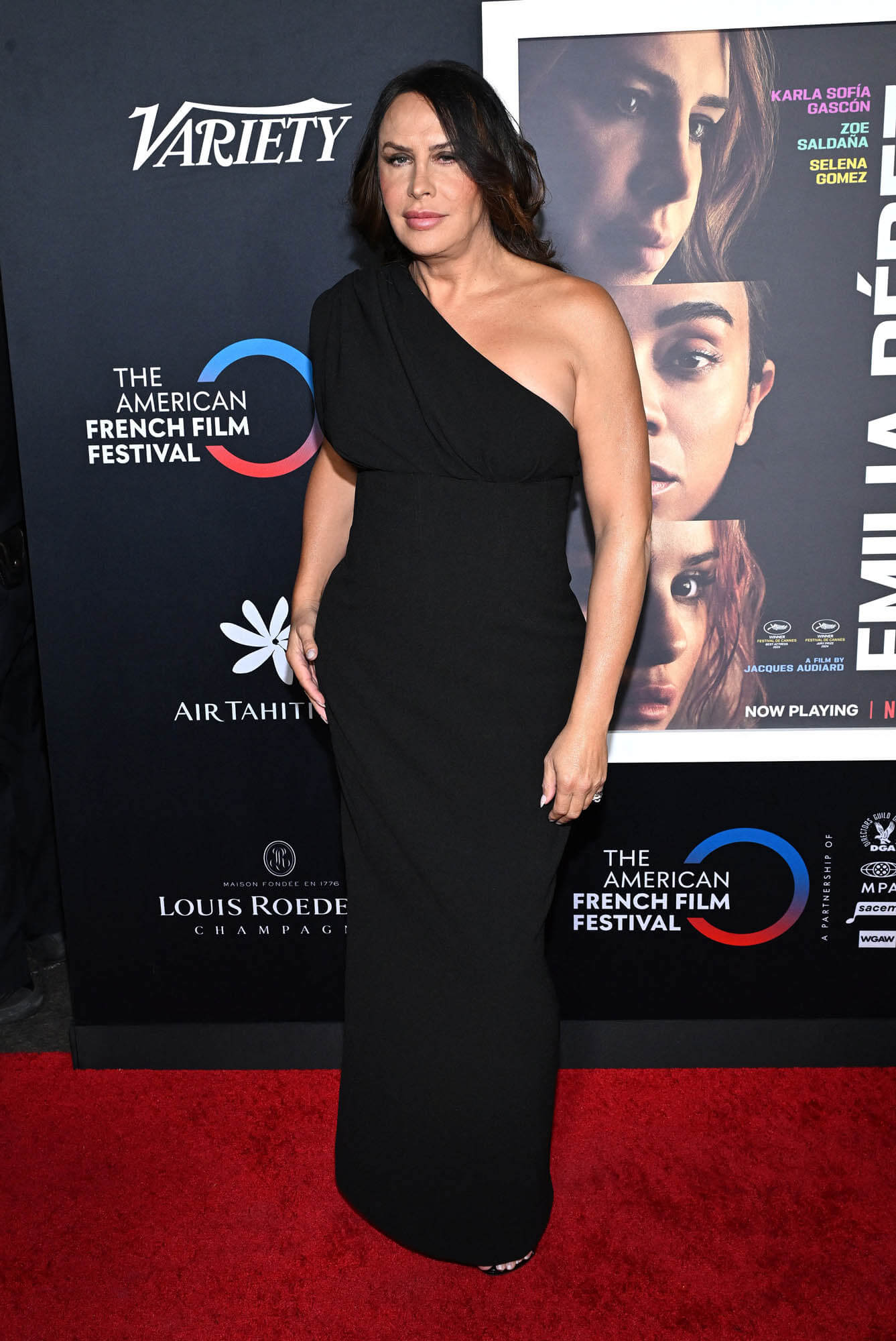

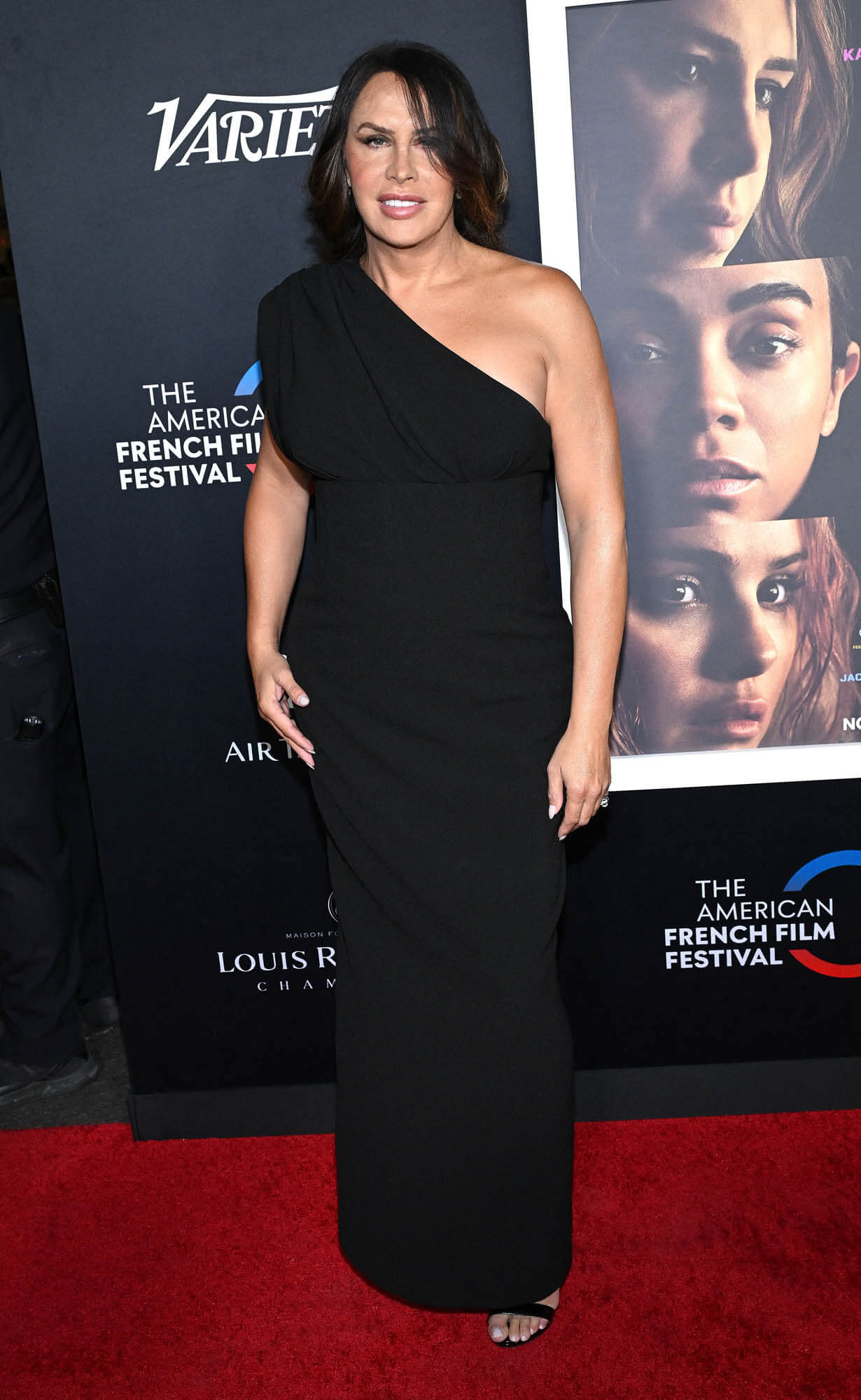

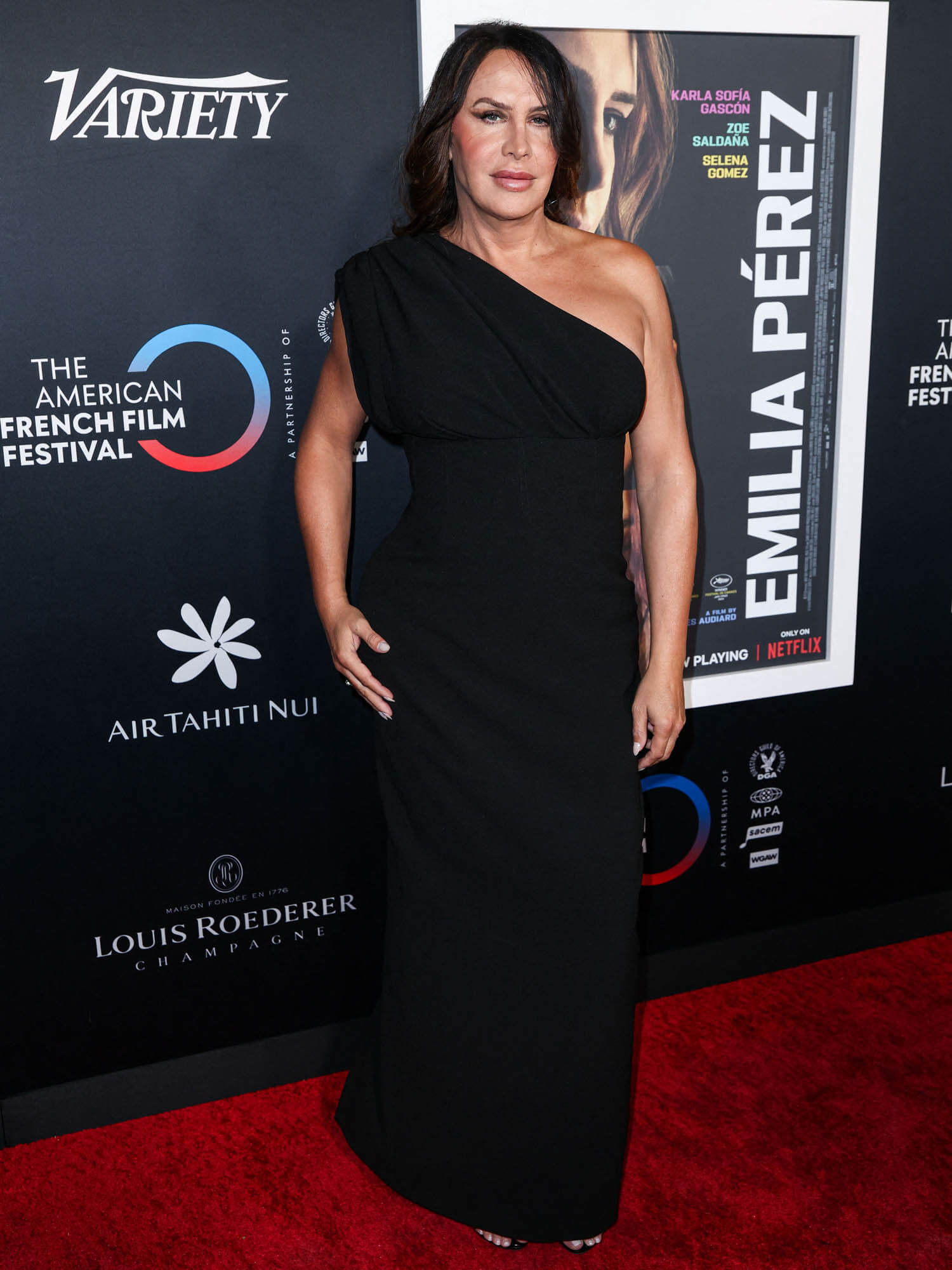

Saldaña, Gomez, and Gascón in Emilia Pérez

My dislike of musicals is well documented and sometimes people will ask why I dislike musicals, and I now have a succinct answer to that question: Emilia Pérez is why I dislike musicals.

Jacques Audiard’s award-winning cinematic musical embodies everything that I don’t like about the form. Musicals ask an inherent question—why does this story need music? A good musical at least has catchy songs, a great musical is one in which musical expression is essential to our understanding of the characters and narrative. In a great musical, song cannot be separated from story (such as in Chicago or Guys and Dolls). Emilia Pérez is not a great musical because music is not essential to its narrative, it’s not a good musical because its songs are not catchy. Emilia Pérez is, then, a bad musical by default. It’s also a bad film. Why are we taking it so seriously?

Probably because the acting is very good. A group of talented actresses throw everything they’ve got into Audiard’s misguided mess, and together stars Karla Sofía Gascón, Zoe Saldaña, Selena Gomez, and Adriana Paz manage to make something watchable out of it. Note, I did not say ENJOYABLE. Emilia Pérez should be wildly entertaining based on its ambition alone, and it presents itself as if it IS some kind of radical work, but a more pedestrian depiction of the trans experience I cannot imagine. Every cliché—many harmful negative stereotypes—is present, and Audiard has nothing to say about any of the complicated realities he sets up for his characters.

The film is centered on three primary characters, attorney Rita (Zoe Saldaña), her client Emilia Pérez (Karla Sofía Gascón), and Emilia’s ex-wife, Jessi (Selena Gomez). The film begins with Emilia hiring Rita to orchestrate her gender transition and fake death, so that Emilia can escape from her life as cartel kingpin Juan “Manitas” Del Monte and live instead as her true self, Emilia. This will involve shuffling her wife, Jessi, and children to Switzerland. To prove her commitment to her new life, Emilia shows Rita her chest, and Rita recoils in disgust from what are presumably Emilia’s breasts, formed after years of hormone therapy. The audience does not share Rita’s perspective, but the sight of Emilia’s chest is treated as a moment of body horror, which is an interesting choice for a film that purports to be supportive of transwomen. It’s the “you’re so brave” of queer cinema.

There is probably a cisgender man who can make a sensitive yet bold film about a transwoman, but Jacques Audiard, who adapted the screenplay from Boris Razon’s novel Écoute, is not that man, mainly because he is so uninterested in his own characters. There is no exploration of anyone’s interiority, Jessi doesn’t even HAVE interiority, neither does Emilia’s eventual love interest, the aptly named Epifanía (Adriana Paz, doing the most with the least). Emilia exists in a gender essentialist binary in which men are evil brutes and women are forgiving saints. When Emilia must deal with remnants of her past life, she adopts a deeper, more masculine voice, as if she, as herself, is simply incapable of doing and saying the things Manitas once did.

This could be fertile emotional ground to explore, if Audiard had any interest in reconciling Emilia’s past and present realities, but instead, he approaches Emilia’s transition as if it really did kill Manitas, and Emilia is a stranger forced to pick up the pieces of this other person’s violent life. There is no subtlety or nuance in Emilia’s experience, which makes her post-transition life completely insane. Emilia, who once orchestrated the disappearances and deaths of hundreds, if not thousands of people, opens a charity to help families locate their missing loved ones and, hopefully, give them proper burials. Again, this could be an avenue to explore Emilia’s deeply conflicted sense of self, her regret and self-recrimination over her past crimes, but the film treats this as if Emilia is a totally separate entity who bears no responsibility for what Manitas did.

I haven’t even mentioned the subplot in which Emilia contacts Rita to once again orchestrate changes in her life, bringing Jessi and their children back to Mexico to live with Emilia, who is presenting herself to her family as a long-lost aunt. Emilia Pérez is Mrs. Doubtfire by way of Sicario with a dash of Gaslight and Guys and Dolls. And that SHOULD make for an entertaining, if messy, film but Emilia Pérez lacks the deeper thematic explorations and character intimacy that could unite such an ambitious blend of genres and styles into something interesting and engaging.

Never mind it’s just a bad musical! The music is bad! The original music comes from Clément Ducol and French singer Camille, and the dance numbers are choreographed by Damien Jalet. There is not one good song in the bunch. If Emilia Pérez accomplishes anything, it’s making me appreciate Leos Carax’s similarly bonkers serio-comedic musical, Annette, even more. At least Annette has good music! And Jalet’s choreography MIGHT be good, but it’s photographed so poorly—truly, Patti LuPone is right people do not know how to film musicals anymore—you can’t make heads or tails of it. I long for a full body shot! Let me see the dancing! Not showing it to me makes me think it’s bad! The costumes are good, though. Hat’s off to Anthony Vaccarello for the clothes. Emilia Pérez is another film for the rapidly growing pile of “ambitious but deeply flawed films by singular directors” released in 2024.

Emilia Perez is now playing in select theaters and will stream exclusively on Netflix from December 13, 2024.