The Audacity of Black Panther

When I was three, my big brother Sam smacked me on the head with a mini model car. He was five and frustrated that I kept stealing his toys. The incident left a small but permanent scar in the middle of my forehead. Throughout my childhood and into my early adulthood, I was ashamed of my scar. I hid my forehead under blunt bangs for years. Sam jokes that he put that scar there for a reason, and that I should be grateful because it adds character to my five-head. He’s always said that I should be proud of my scar.

There is a moment in Black Panther, when the light hits Shuri (Wakanda’s chief tech innovator and T’Challa’s little sister) just right and I noticed that Letitia Wright has an indent on her forehead almost identical to my scar. I was already emotional, obviously, but in this moment, the little girl who grew up watching superhero movies with her big brothers, who felt shame not only of her scar but also of her hair, her skin and the oxtail lunches her mom packed for school, was right there with me watching Shuri and seeing herself reflected on screen. To be clear, growing up I never wanted to be anything other than black, the daughter of Ghanaian and Jamaican immigrants; I just knew that I was supposed to feel embarrassed by these things based on my surroundings and everything pop culture told me, so I did. But there is no shame in Wakanda, only pride. The pride of Wakanda is radical, it’s in-your-face, it’s unlike anything we have ever seen in a mainstream film about Africa, and therein lies the audacity of Black Panther.

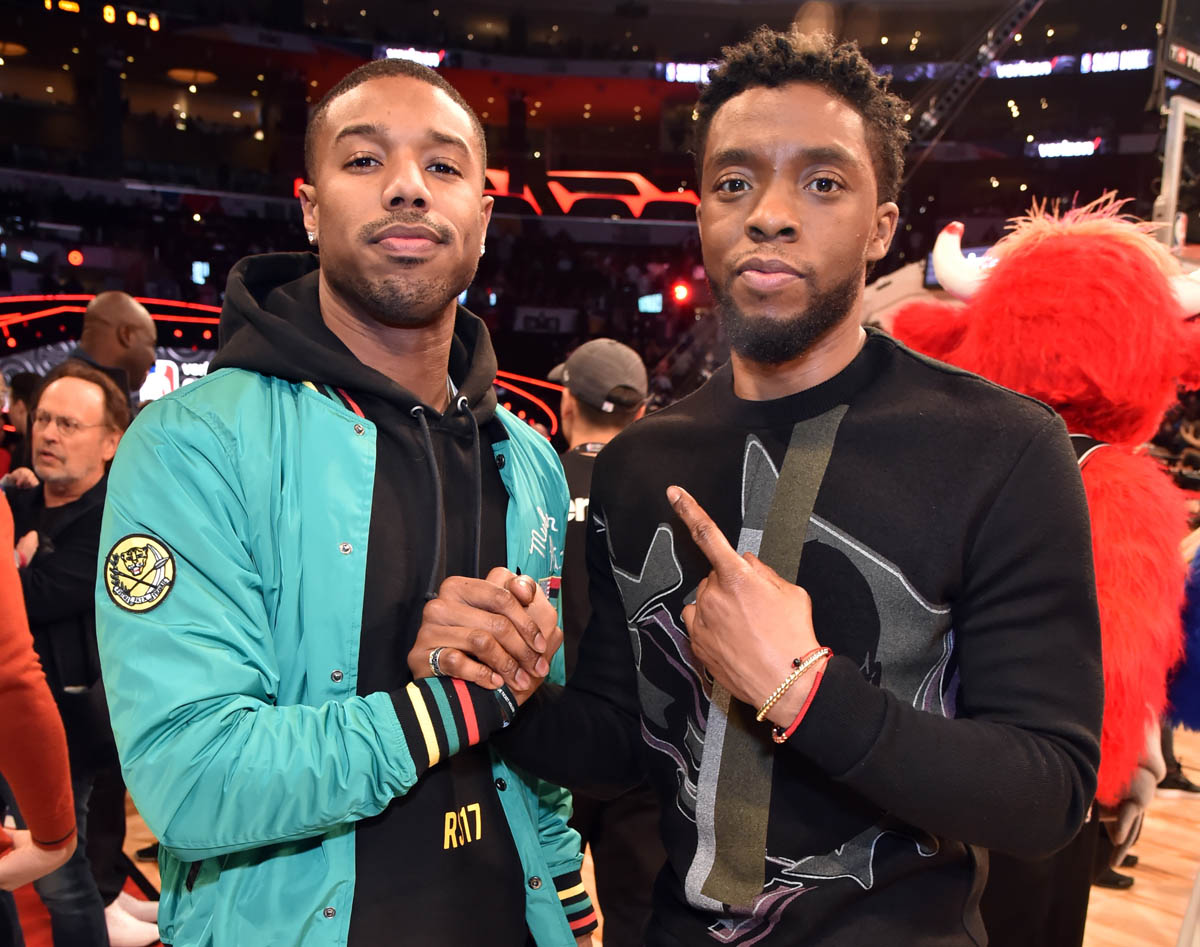

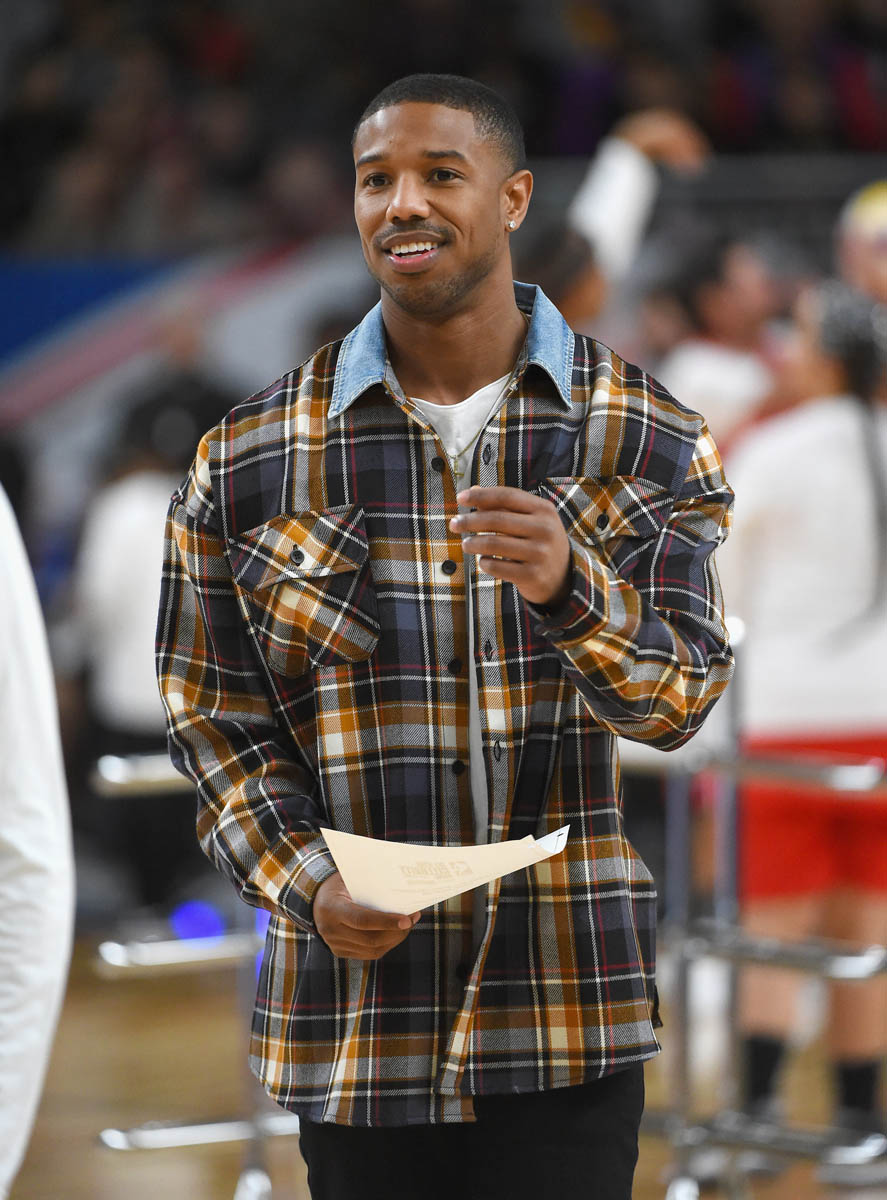

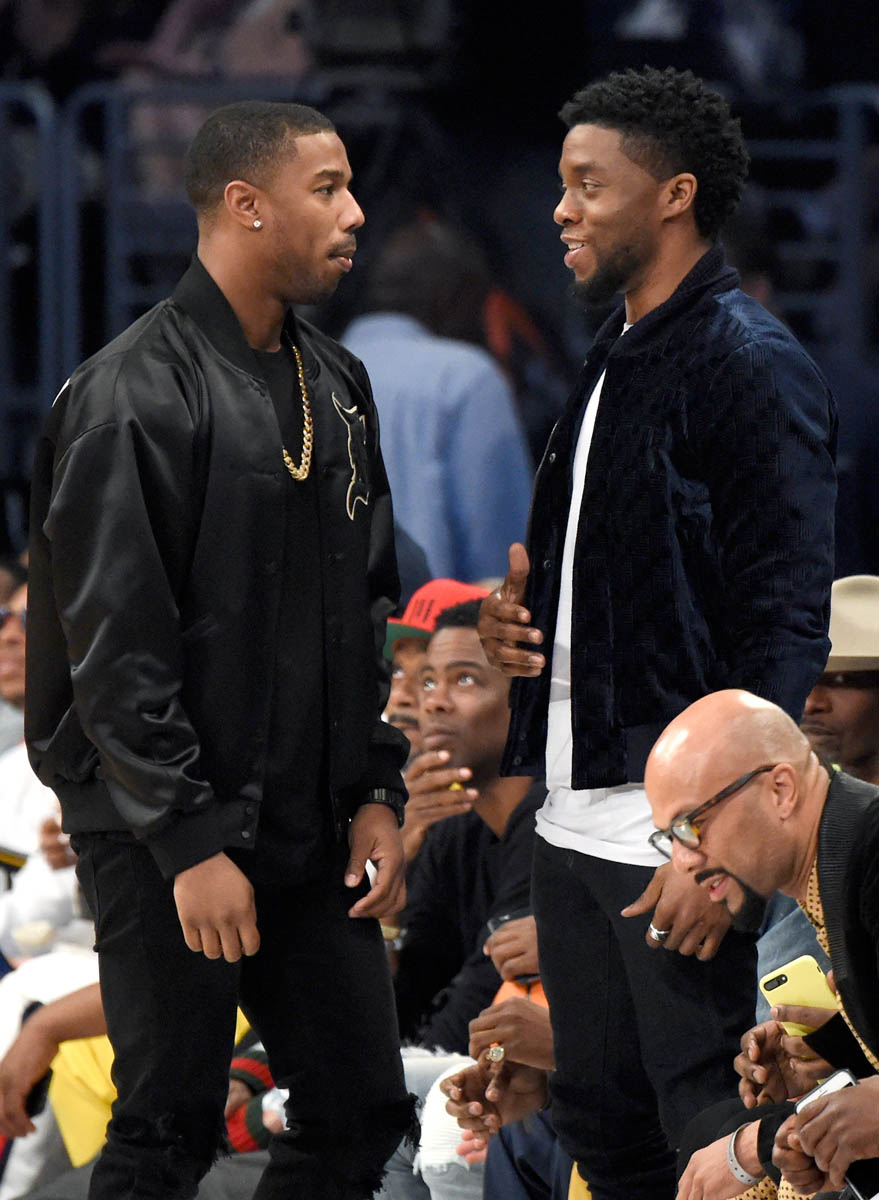

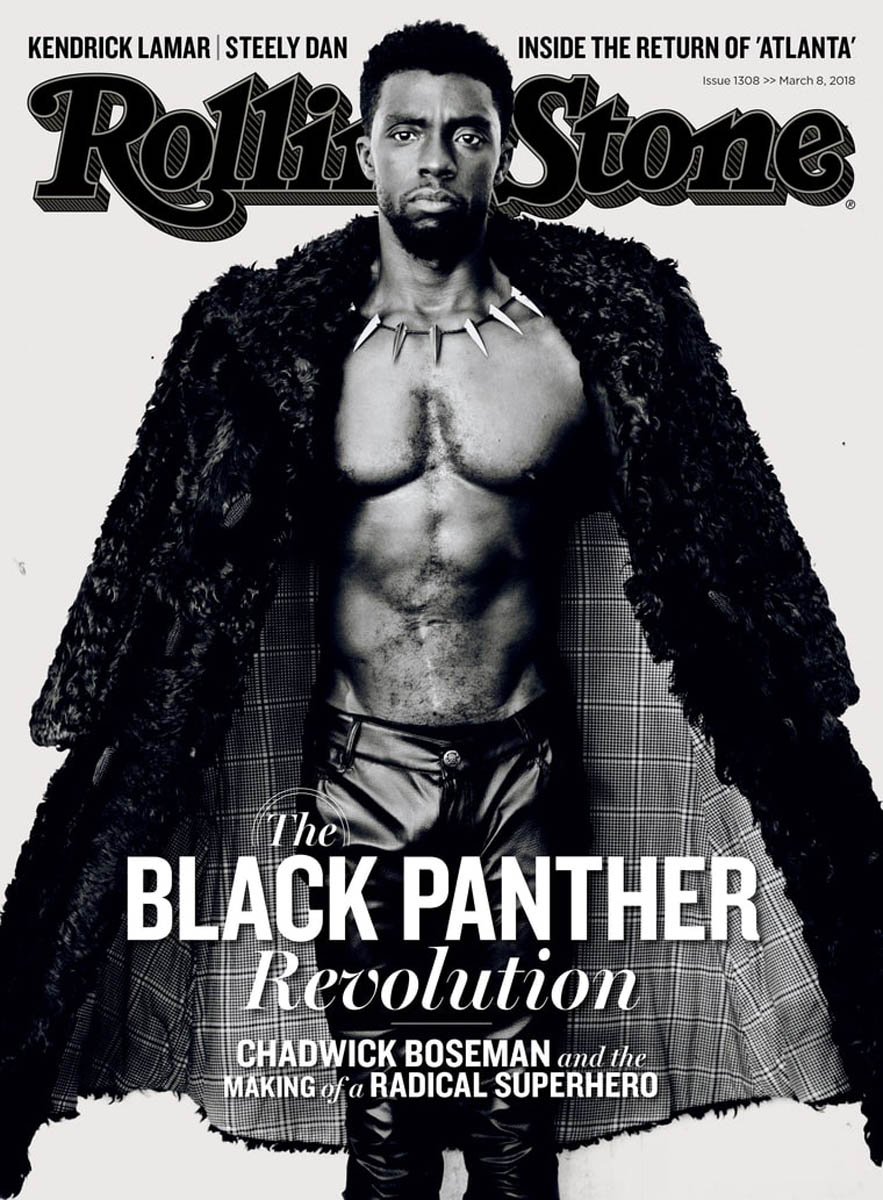

Eric Killmonger is Marvel’s best villain – arguably the best villain in a superhero movie, ever. Our resident Marvel scholar Sarah praised Killmonger’s villainy in her review so that’s not just my Michael Bae Jordan bias talking. We’re going to be reading think-pieces on think-pieces on the complexity of Eric Killmonger for weeks to come. There are two lines that Killmonger says that, aside from Letitia’s scar, I have thought about every day since I saw Black Panther the first time. By viewing number three, these two lines have come to embody what Black Panther means to me personally, and for, as the kids say, the culture. They exemplify why this movie is audaciously black, yes, but also why it’s a tale of black identity and black responsibility.

“My father said that one day he’d take me to Wakanda, the most beautiful place in the world... Can you believe that? A kid from Oakland running around believing in fairy tales.”

That’s line number one. To me, this line is for Ryan Coogler, a kid from Oakland himself who has now become the wunderkind director of a Marvel film smashing box-office records as I type this, but this line is also for all of us. It’s for all the grown-up black kids who never dared to believe a film like this could exist. It’s for all the black kids growing up now who will get to run around believing in fairy tales starring themselves, their mothers, their fathers, their sisters and brothers. I never dared to dream that Shuri could exist. T’Challa is my brother’s greatest dream fulfilled. The vibrant, fully-formed, badass, dark-skinned women of Wakanda are beyond my mother’s wildest dreams. Wakanda may not actually exist but, as Jelani Cobb exquisitely writes for The New Yorker, neither does the shallow depiction of Africa that has always existed in pop culture.

Wakanda is no more or less imaginary than the Africa conjured by Hume or Trevor-Roper, or the one canonized in such Hollywood offerings as “Tarzan.” It is a redemptive counter-mythology. Most filmmakers start by asking their audiences to suspend their disbelief. But, with Africa, Coogler begins with a subject about which the world had suspended its disbelief four centuries before he was born.

Wakanda may seem like it’s just a fairy tale land created by Marvel and brought to screen by Coogler but if you’ve been to any of the epic cities across the continent, you know that they too are hiding in plain sight. They are not the Africa you see in World Vision commercials. I can speak to Accra, Ghana because my family is there and I daydream about going back, daily. Being there was like stripping all those silly insecurities away. It was like coming home. It was also an education because, despite all my dad’s stories and my cousins’ letters, as a naïve teenager I too had fallen victim to some of the preconceived notions of Africa that pervade Western culture. I was always proud to be Ghanaian but I don’t think I was expecting to feel such a sense of belonging or the urge to go back, immediately. I’m not sure if I anticipated being awestruck by Accra. Accra is not what the world thinks Africa is. Neither is Lagos or Johannesburg. Or so many more. These cities may not have hover bikes or the Dora Milaje but the beauty of Black Panther is that it is reflecting an image of Africa that does exist, while asking questions that address the complexity and pain of African history – as well as African-American history.

Which brings me to the second line that has burrowed its way in between the scar-marked skin of my forehead and my cerebral cortex. I imagine it sits there, replaying over and over, reminding me of this movie’s brilliance.

“Nah, bury me in the ocean with my ancestors that jumped from the ships. Because they knew that death was better than bondage.”

This was said in a Disney movie. A Disney movie about superheroes! RYAN COOGLER DID THAT. Let the man direct every Marvel film from now until forever. Give Michael B. Jordan an Oscar for the way he delivers this line. I just had to stan for Coogler and MBJ for a second because good lord, this line. Not only does it make a direct and uncomfortable (for the white people watching) reference to slavery, it also ties together the two dueling ideologies of Black Panther. You can interpret Wakanda’s hard stance of hiding itself from the rest of the world as a way of staying free of the death vs. bondage choice, but you can also interpret it as a betrayal of the people who did have to make that choice.

Jelani Cobb’s New Yorker piece that I referenced earlier refuses to categorize Killmonger as a villain.

… the two characters are essentially duelling responses to five centuries of African exploitation at the hands of the West. The villain, to the extent that term applies, is history itself.

The villain is history itself. God, that’s brilliant. Try to tell me this is just a dumb action movie. TRY. One of my favourite scenes – and the one that got the most raucous response at each of my screenings— is when Shuri flippantly denigrates one of the only white characters in Black Panther by calling him “Colonizer.” That same character is barked over when attempting to speak a few scenes later. Believe me when I tell you that Black Panther depicts blackness AND whiteness in ways we have never seen. And this is just the beginning.

We talk about representation often. The importance of Black Panther as an all-black film is paramount but that’s not where its significance ends. This weekend, I scrolled through Twitter joyously taking in all the pictures of beautiful black people dressed in kente cloth, dashikis and African prints heading to the theatre to revel in this momentous occasion. When I saw it last Thursday, I waited outside of the theatre for my brother in tears watching everyone arrive like it was their very own Royal Attire Requested premiere. Some may call this extra. They may not understand how one movie can spark so much joy or bring together so many different communities with one thing in common. I am overjoyed that the next generation has Shuri, Okoye, Nakia, M’Baku, T’Challa and Queen Ramonda to look up to but also that this movie’s success will make it so that there will be many more movies like this with characters for them to look up to. And maybe their dreams will be less clouded by images of shame or erasure. Black Panther is smart, funny and so damn good. It’s a shining beacon of permission to be unapologetically excellent and brazenly black. What does it look like if every black kid is given the hope to believe that their scars are something to be proud of, that their dark skin is beautiful, that their minds are capable and that they are more than worthy? That’s the audacity of Black Panther.

Wakanda Forever.