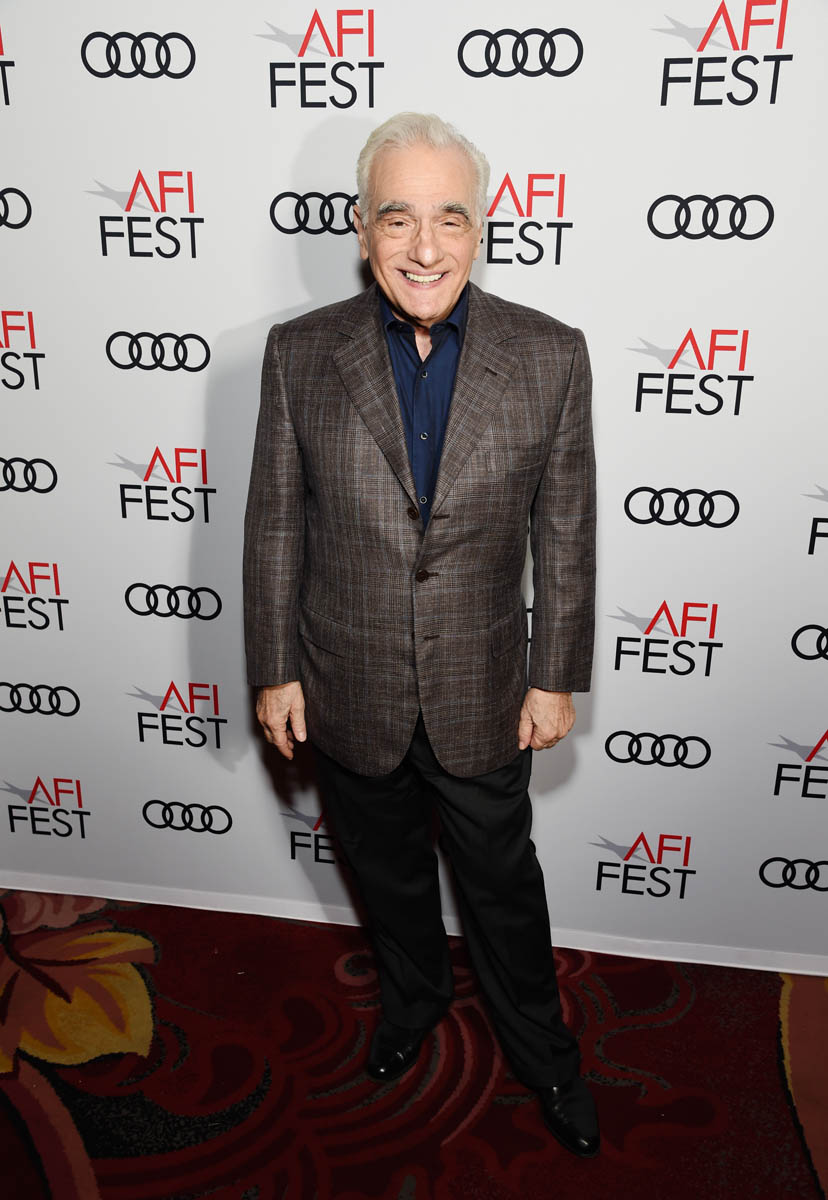

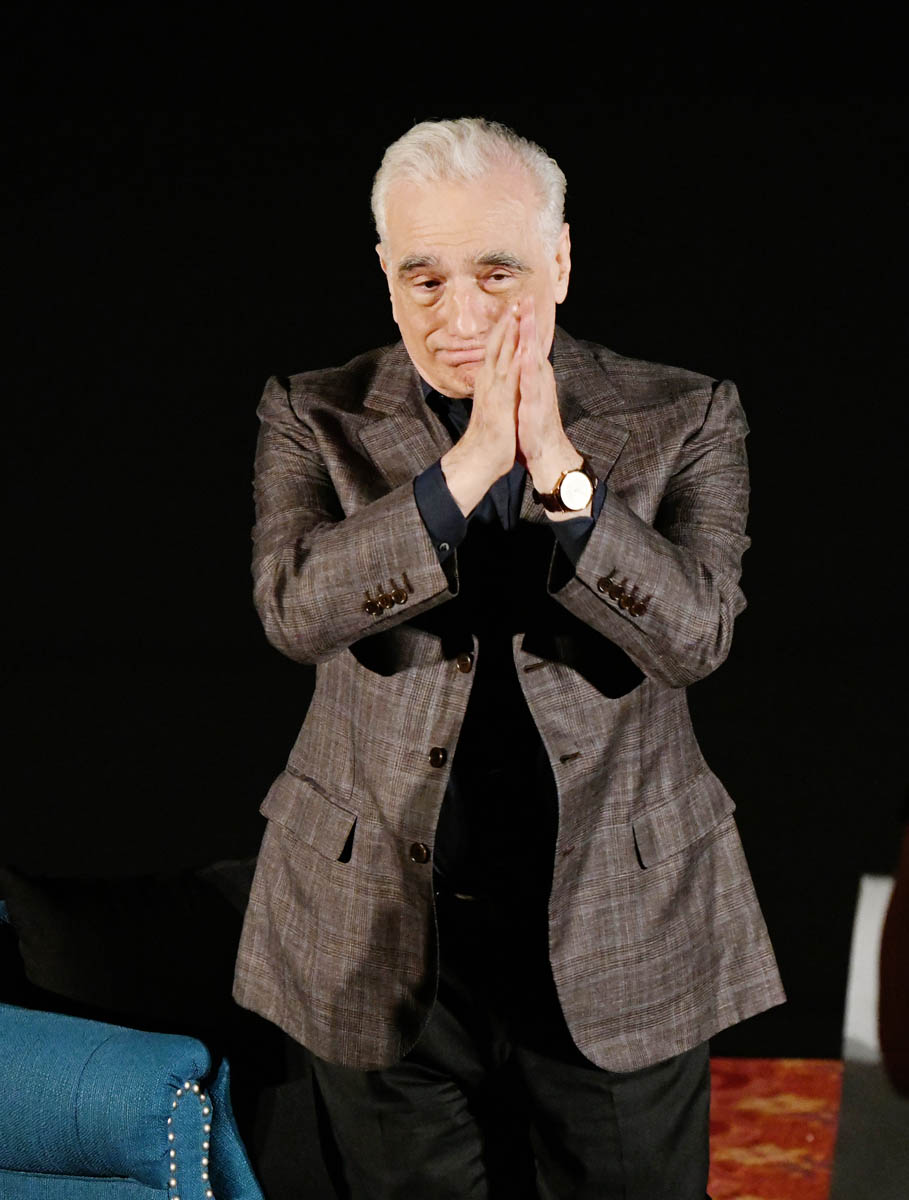

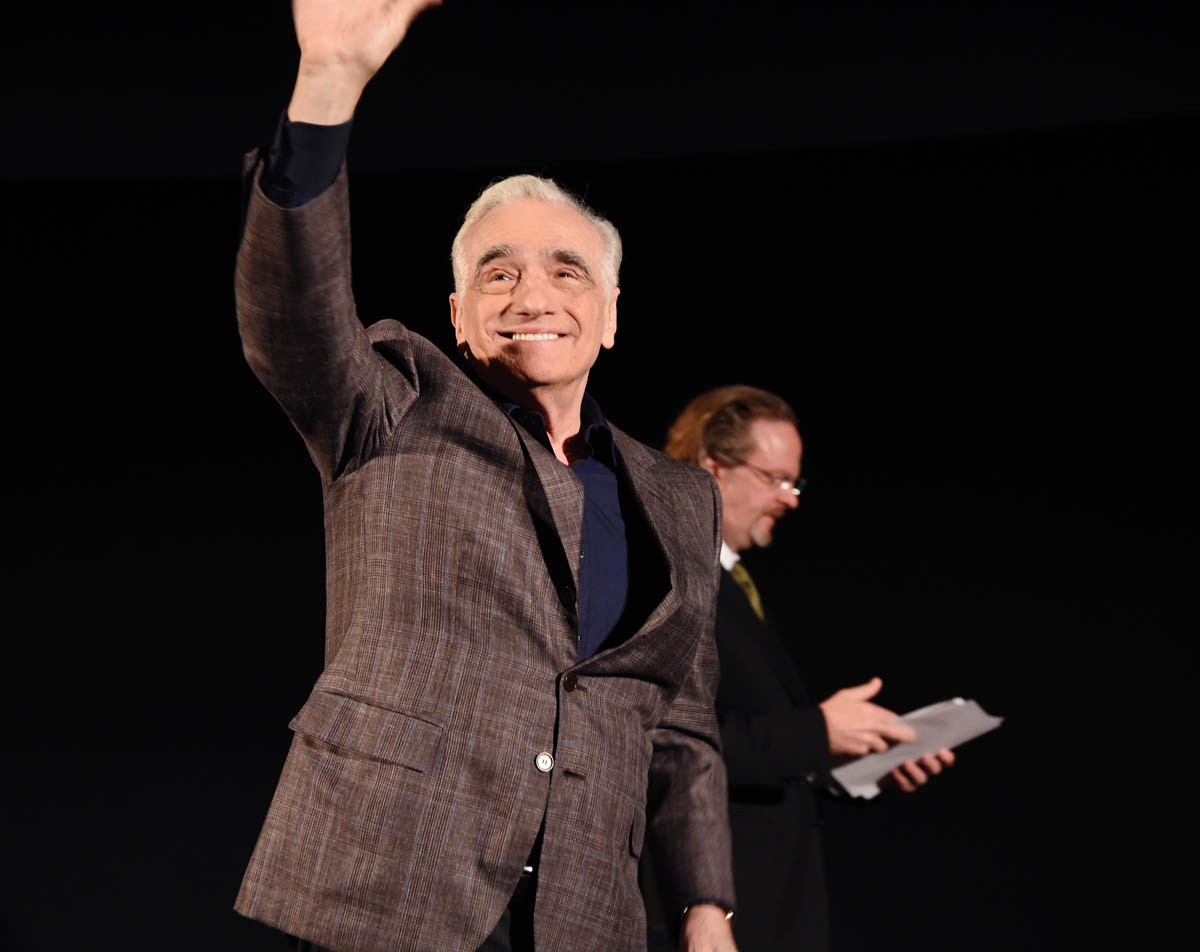

The Irishman is Scorsese’s least glamourous gangster film

Based on either a true story or an entertaining lie, depending on how hot your conspiracy thermometer runs, The Irishman is the story of Frank Sheeran (Robert De Niro), a union worker and alleged mob hitman who claimed at the end of his life to have assassinated Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino). A three-and-a-half-hour opus from Martin Scorsese, The Irishman is a gangster movie that is equally interested in the mechanics of the mob life, and the heavy price paid by those who live it, especially if they have the misfortune to survive to old age. This is a film that is as concerned with the cruelty of age as it is the cruelty of men, and The Irishman walks a fine line between empathy for the human condition and sympathy for the devil.

The film, narrated by Frank as an old man in a nursing home, traces Frank’s life from World War II to his final days in the early aughts. De Niro plays Frank all the way, which means the digital de-aging process is deployed to render him a twenty-something in the war, a thirty-something rising up the ranks, and a middle-aged man tied up in one of the most famous disappearances of the twentieth century. The tech is not terribly distracting, though there is a definite Call of Duty look to the World War II scenes. There are some glitchy shots, instances where proportions are off—not uncommon with heavy digital reworking of moving images—and more than a few “Jib Jab” shots where people have no necks and their heads seem to float in front of their bodies. And there is definite cognitive dissonance in looking at a young face and hearing an aged voice come out of its mouth or seeing a “young” character move like an old man. But it’s a testament to the storytelling of The Irishman that even the noticeable imperfections of the tech do not sink the film. Do the distractions fall away as the characters age and require less retouching? Yes. For sure. But The Irishman is engaging, even when your brain hangs up on the visual inconsistencies.

Frank falls into the mob life through his job as a delivery driver, and he does well because killing doesn’t seem to bother him. But throughout the film, we see the toll his “work” takes on his family, especially the estrangement of his eldest daughter, Peggy (Anna Paquin). No, Peggy doesn’t talk much, and no, she is not a central character. But in her few scenes and with a minimum of words, Paquin captures the anxiety and outright fear of living with someone like Frank and suspecting—knowing—he has not just killed someone, but killed someone you respect. From the time she is a little girl, we see the chasm growing between Frank and Peggy, and Paquin caps it off with a nervy performance of a woman in full flight from a man who terrifies her. Counting lines is a stupid way to measure a character’s relevance in a story; look at how the character impacts the narrative and drives the choices of other characters. In Peggy’s case, she removes choices from Frank, closing him out, and isolating him in his dotage. This is not the central relationship of the film—and maybe the better conversation is why not see this story from Peggy’s perspective—but it is critical to understanding what Frank sacrifices to be a cool mob dude.

Although this is probably Scorsese’s least glamorous gangster film. Sure, there are plenty of classic Scorsese tracking shots, and a slick recurring music cue with “In the Still of the Night”, and even a funny bit where minor characters have their dates and causes of death displayed on screen (which reminds me of the I Think You Should Leave baby pageant sketch). But The Irishman is really invested in what it takes to succeed with the mob, which is, ultimately, a willingness to sacrifice anything, including genuine friendship and your own family’s affection, in order to…end up in jail. The worst thing that can happen to a mobster isn’t being gunned down in the street by someone like Frank, it’s outliving your relevance. These men, once so powerful they practically ran the country, end up no different from any other elderly person, struggling against failing bodies and minds, rendered helpless by stroke and disease, and even their greatest “accomplishments” fade into the mists of time as younger generations forget their infamous deeds.

The Irishman is, in one sense, a classic Scorsese gangster film, but it is also a film Scorsese could only make now. This is not a young man’s film, about the foolishness and vagaries of misspent youth. This is a film as much about aging and end-of-life regret as it is the mob, if anything, the extreme nature of Sheeran’s story only highlights the consequences we all must face as we age. For all the power and reputation Frank amasses, he has nothing to show for it except a prison record and an estranged family. Honestly, The Irishman doesn’t need the technical gimmick to sell its story, because the best part of the film is the final half, when Frank and his cohort live to see their glory fade and power wither. It is there that The Irishman is at its most humane and its most unforgiving, as all the perceived prestige and power of the mob fades with time, and all that is left is a lonely old man with no one to visit him.