TIFF Review: Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is one of the most enduring works of English literature, often considered one of the first, if not the first, science fiction novels, as well as an early flagship in horror literature. It has been adapted and reimagined countless times over the centuries, the latest iteration comes from Guillermo del Toro, whose love of monsters and empathy for outsiders makes him an ideal adapter of Shelley’s tale.

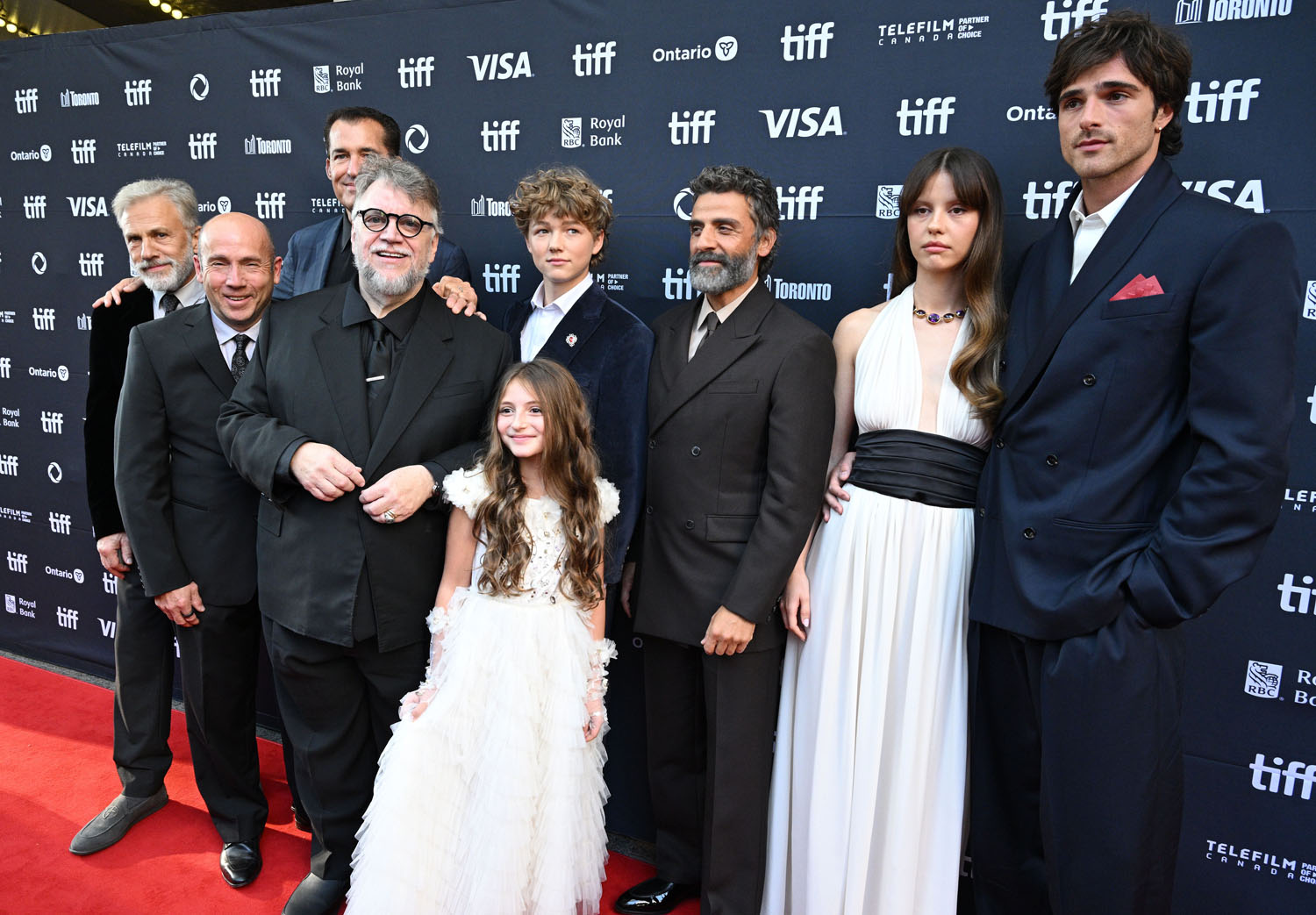

Del Toro, working off his own adaptation of Shelley’s novel, takes his biggest liberties with the first half of the film, the portion told from the perspective of Baron Victor Frankenstein. As a boy (Christian Convery plays the young Victor), he has a close relationship with his loving mother, but a cold and abusive relationship with his distant, demanding father, a renowned surgeon (Charles Dance appears as the elder Frankenstein, he can do these roles in his sleep and nothing against Dance, who is a terrific actor, but I do wish filmmakers would use a little more imagination when casting British assholes). Victor’s mother dies in childbirth, though, leaving Victor with a younger brother and no respite from his father’s viciousness. Grief stricken at the loss of his mother, Victor vows to do what his father couldn’t and defeat death.

We next find Victor as an impassioned young medical student in Edinburgh. From here, Oscar Isaac portrays Victor with a wild-haired, wild-eyed mania and rockstar swagger that slowly morphs into an exhausted countenance and labored step. Victor is on the brink of expulsion, and his only defense is his belief that doctors should be in the business of stopping death entirely, not just delaying it. To this end, he demonstrates his work which involves reanimating a partial cadaver. It is super gross. If you’re not into blood, gore, and viscera, this is definitely not the film for you. But Frankenstein is the perfect material for del Toro to get deep into his love of juicy innards, there is lots of gross body horror liberally peppered throughout the film.

While Victor’s demonstration does not save his medical career, it does attract a benefactor, a wealthy man called Harlander (Christoph Waltz) who promises Victor unlimited funds and an appropriately gothic laboratory in which to perform his experiments. At the same time, Victor’s younger brother, William (Felix Kammerer), re-enters Victor’s life, along with his beautiful fiancé, Harlander’s niece, Elizabeth (Mia Goth). Victor is predictably smitten with Elizabeth, a Victorian sad girl whose whole vibe is “sweet death! Embrace me!”.

Del Toro’s sensibilities are a perfect match for this material. Narratively, he slants the first portion of the story told from Victor’s perspective toward cycles of abuse and fathers and sons. As Victor was once beaten and treated without love by his father, so, too, does he treat his creation with contempt and abuse. Even his love for Elizabeth is questionable, she looks like his dead mother, and he resented William for receiving affection from their father, so does he truly love her, or does he just covet her to hurt William? Either way, she isn’t buying Victor’s bullsh-t, neither romantic nor scientific. Del Toro has empathy for Victor, who is his own kind of monster, emotionally misshapen by a cruel childhood, but he also doesn’t over-romanticize Victor’s fanaticism. The more determined Victor becomes in his experiments, the less appealing Oscar Isaac is, that rockstar aura vanishing under Victor’s hubris.

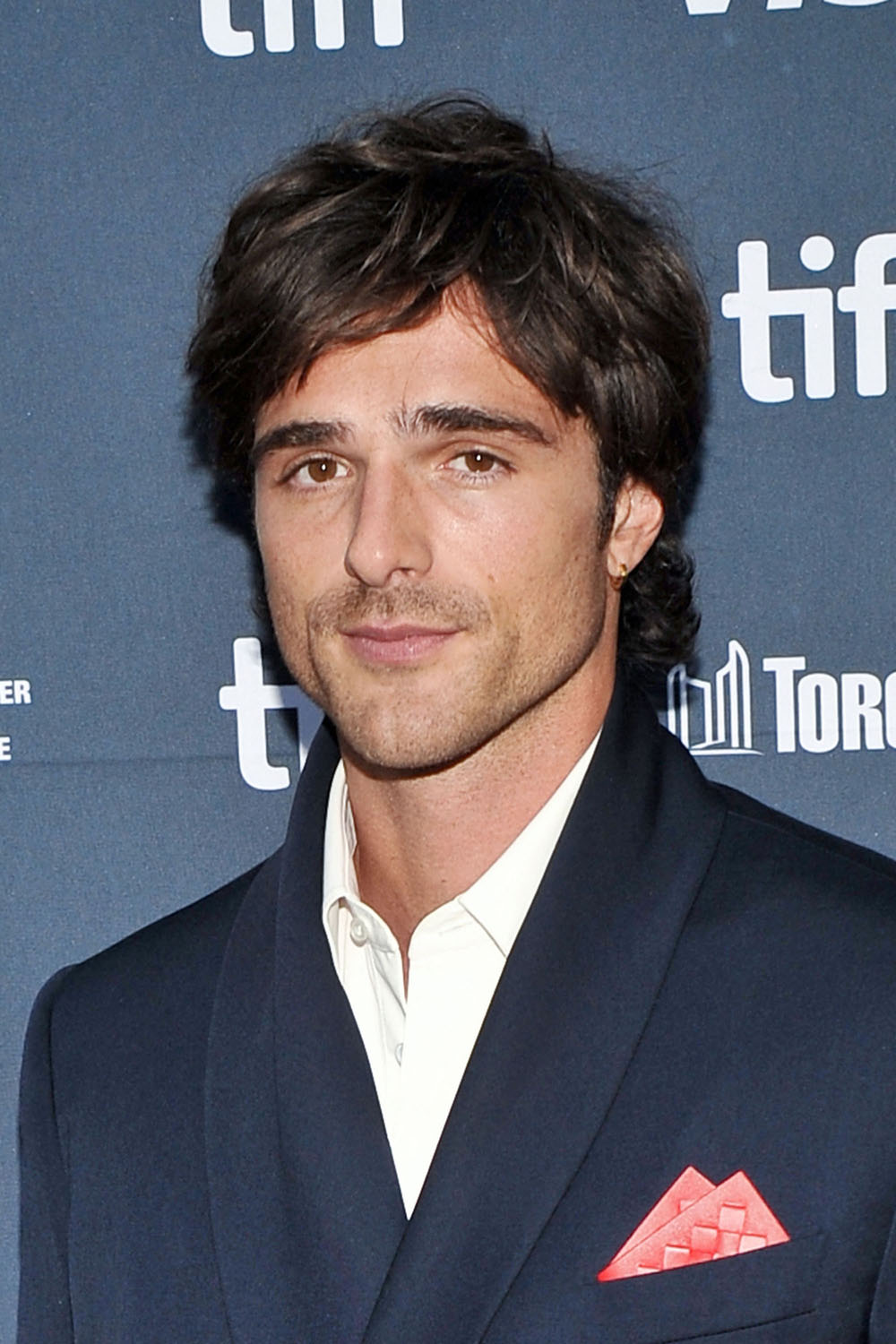

Eventually Victor succeeds in animating a creature composed of pieces of dead soldiers. Jacob Elordi portrays the creature and his is a genuinely moving performance. Buried under a full body suit of prosthetics and makeup—which make him look unnervingly like Nicholas Hoult—Elordi gives an extraordinary physical performance, suggesting not just a newborn infant but also something wretched and strange, his limbs and phalanges moving almost of their own will, his pieces separate from his whole.

The latter portion of the film tells the creature’s tale, and this section of the film hews more closely to Shelley’s work than the first half (purists shouldn’t be looking for fealty, though, del Toro is thoroughly doing his own thing). As he heals and slowly masters himself, the creature’s intelligence emerges, perhaps first kindled by Elizabeth’s kindness, her goodness igniting a spark within him just as Victor’s machine did. Del Toro does not cast Victor as the tragic romantic figure of his story, but the creature emerges as a Byronic hero—dark, mysterious, doomed. He longs for love and to be less lonely, his fury has the flavor of heartbreak when he realizes he is alone in the world, not man and not beast, but some horrible other with no counterpart.

And of course, Frankenstein looks and sounds incredible. Alexandre Desplat provides a good score, but more than that, the sound design (from Paul Germann) is stellar, particularly around the creature’s voice. And the film looks simply spectacular, with the kind of lavish, detailed production design we’ve come to expect from del Toro, aided by cinematography from Dan Laustsen, who already has two Oscar nominations from previous del Toro collaborations (Nightmare Alley and The Shape of Water). But the creature’s design takes the cake. He isn’t beautiful, but he’s also not not beautiful. Not unlike the fish man of The Shape of Water, the outline of a beautiful man is present—height, shoulders, nice hands, great cheekbones, a noble brow. It’s just, you know. Parts of him are kind of rotting.

Like all of his work, del Toro’s Frankenstein won’t be for everyone. It’s gross, there’s a lot of animal cruelty, some child abuse, the unending horrors of man, and so on. And del Toro thematically cants the story in a different direction, making it less about gods and monsters and more about fathers and sons, emphasizing the creature as Victor’s child, mistreated and betrayed by his father just as Victor was by his father (though Prometheus and Paradise Lost, both influences on Shelley, do get plenty of references). But what del Toro achieves is one of his most complete works to date, the form and function of cinema flawlessly united to tell his story. And while that story is a twisted tale of broken hearts, anger, and revenge, it is also deeply empathetic to the lost and lonely. Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein is less a cautionary tale, and more a paean to lost family.

Frankenstein will play in limited theaters from October 17, 2025, and will premiere exclusively on Netflix on November 7, 2025.