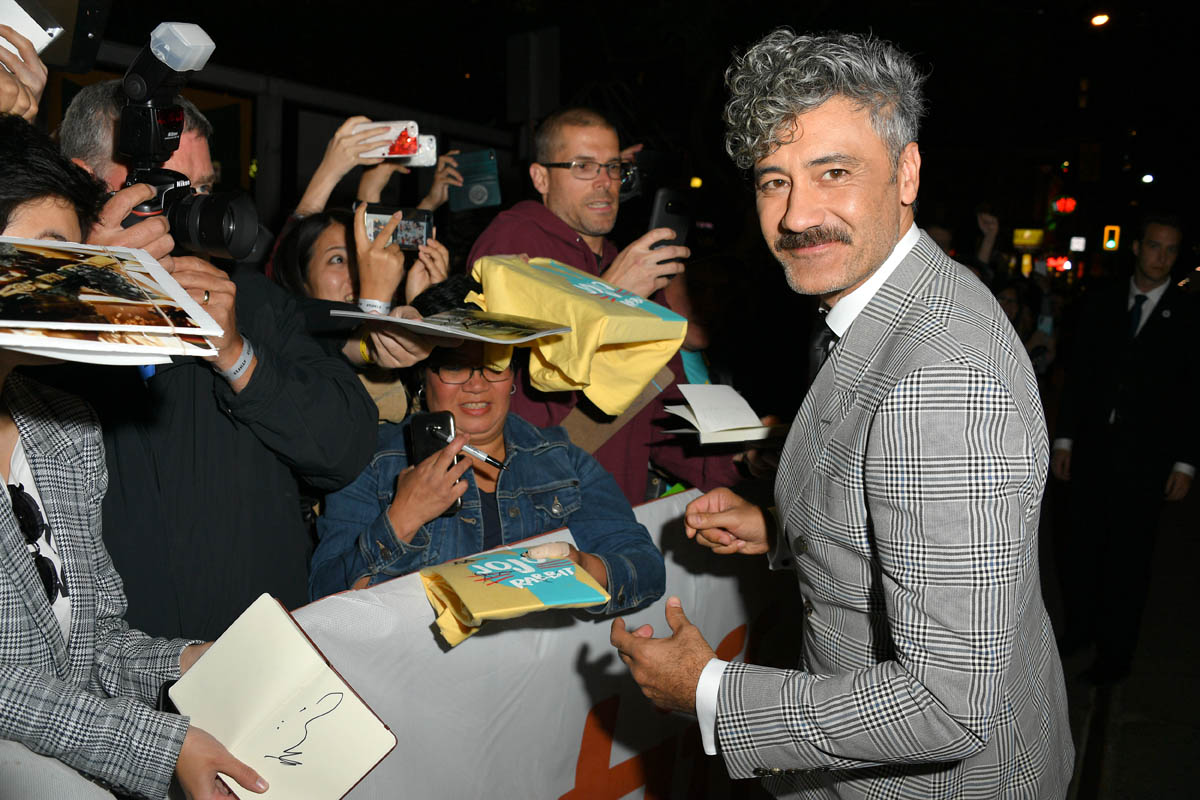

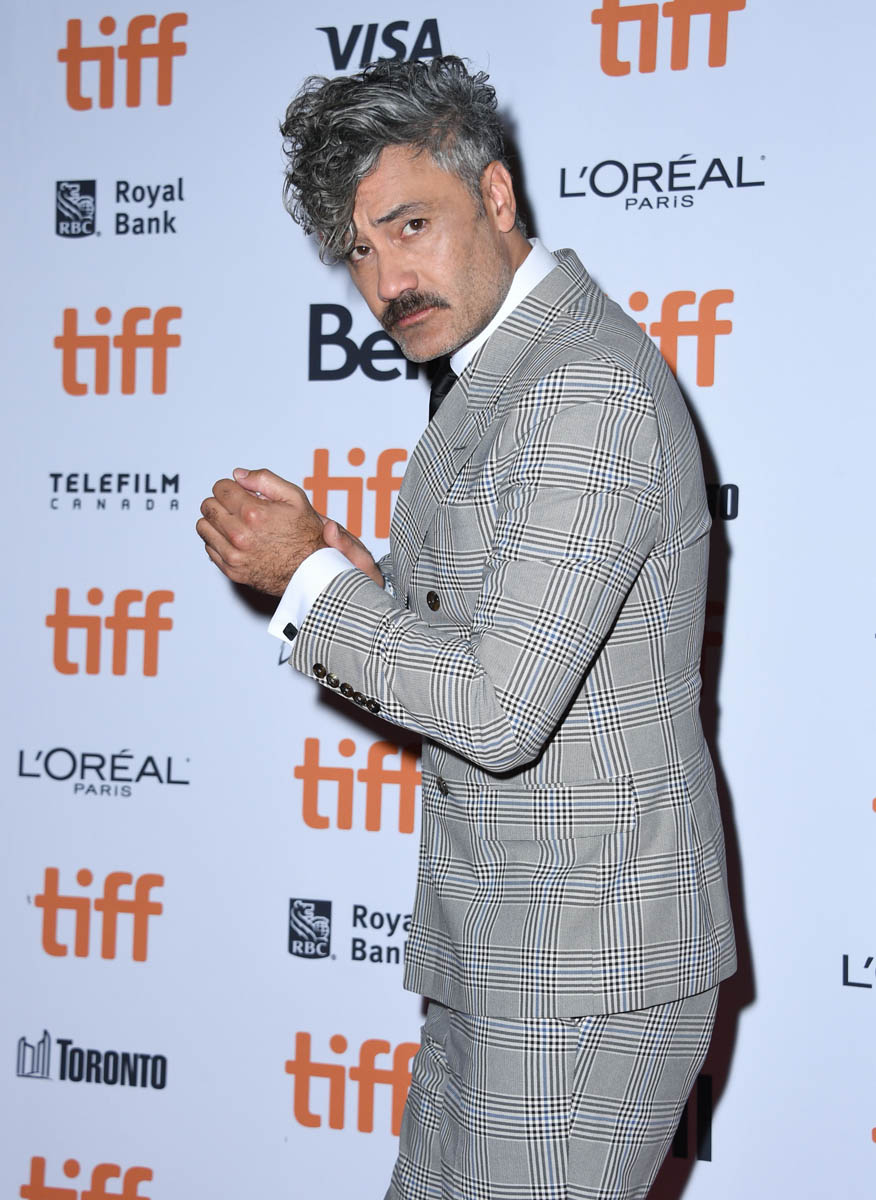

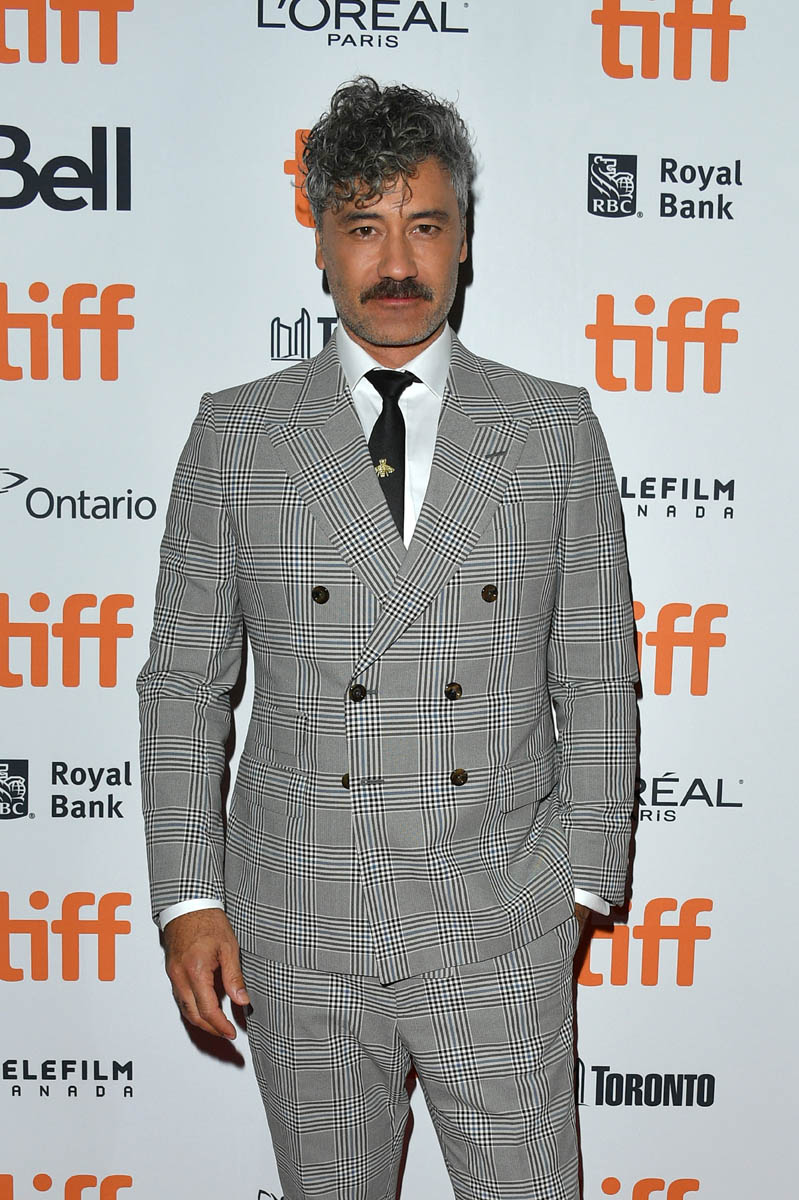

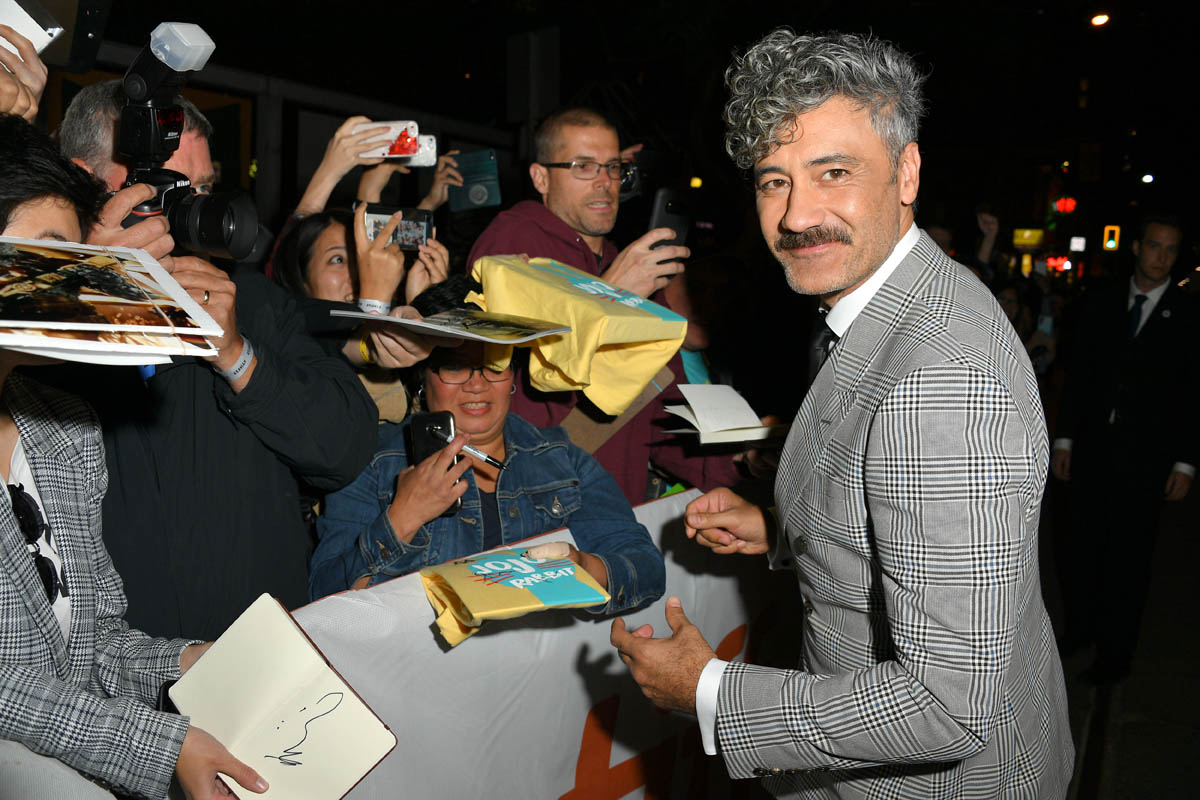

Taika Waititi’s Jojo Rabbit

After playing in the Marvel sandbox, Taika Waititi returns to his natural state, making films with a precise blend of comedy, drama, and pathos. His latest is Jojo Rabbit, in which he becomes the latest filmmaker to satirize Hitler since Charlie Chaplin first did it in 1940s in The Great Dictator. (In that film, Chaplin plays both a Hitler analog and a persecuted Jewish barber, so I don’t know why some people are acting shocked that a filmmaker would dare portray a fictionalized version of Hitler, this is a long cinematic tradition.) Waititi writes (adapting loosely from Christine Leunens novel, Caging Skies), directs, produces, and co-stars in Jojo Rabbit, making this a thoroughly Taika vision—it’s definitely going to be too much for some people. If you’re the type of person who thinks it wrong to mock Nazis and make them the butt of a joke, well, this is not the movie for you. Jojo Rabbit mocks the sh-t out of Nazis, and they are the butt of literally every joke.

And there is plenty of laughter, because Jojo Rabbit is VERY funny. Waititi appears less than expected as Imaginary Adolf, the imaginary friend of ten-year-old Jojo Betzler (Roman Griffin Davis, in his film debut), which is fine. We don’t need a lot of Imaginary Adolf, and Waititi wisely doesn’t overplay his hand. Jojo is lonely and missing his father, who is off fighting in the war—though what Jojo’s dad is doing is a cause of debate—so he has latched onto the only father figure offered to him: Hitler. But his understanding of Hitler and the war is simple and fittingly childish. To Jojo, Nazism is a big club like Scouts, and he is happy to have a group to belong to and someplace to go other than his home, which is haunted by the absence of his father and deceased sister.

However, a hand grenade accident during a Hitler Youth weekend camp—this whole sequence is like Wes Anderson on a bad trip—results in injury to Jojo, which forces him to spend more time at home recuperating with his mother (Scarlett Johansson), who tries to maintain some semblance of a childhood idyll for Jojo. He also works for the local propaganda office, headed by disaffected officer Captain Klenzendorf (Sam Rockwell) and his sycophantic second in command, Finkel (Alfie Allen). In typical Taika fashion, there is an entire tragic story embedded in Klenzendorf, don’t blink or you’ll miss it. Then one day Jojo hears a sound upstairs and discovers his mother has been hiding a Jewish girl, Elsa (Thomasin McKenzie). Jojo is almost completely brainwashed by this point, and finding Elsa is either going to make or break this otherwise sweet kid.

There is SO much sweetness in Jojo Rabbit. This film is well and truly centered on a child’s experience of World War II, and though the sweetness may seem at odds with the subject matter, Waititi cleverly weaves information about the era into his mise en scene. Jojo runs around “heil Hitlering” everyone he sees, but no one responds except for the actual Nazis in town (and even some of them don’t seem too enthusiastic about it). There are no men in town, except for, again, the Nazis posted there. And there is already a sense among the adults that the war is going badly—every time Jojo proudly exclaims Germany will triumph, someone shuts him down. Jojo Rabbit would not work at all but for Waititi’s care in managing tone but also ensuring that any “positive” representation of Nazism is strictly the perspective of a sheltered child who really doesn’t know what is going on. The adults know what’s up, though, and Jojo succeeds thanks to that juxtaposition.

It also succeeds because Jojo Rabbit takes a heartbreaking turn. Jojo can’t remain so innocent forever, not in the darkest conflict in modern history. The war comes home in a very personal way, and Jojo begins to lean more on Elsa. As their friendship grows, Jojo’s relationship with Imaginary Adolf sours, and he begins to see more of the reality around him. As Jojo’s eyes open, the colorful town facades Waititi showed earlier in the film fade and peel, and more obvious signs of suffering and strife appear around town. It’s another subtle touch that balances Jojo’s largely pretend world of heroes and monsters.

Jojo Rabbit is sweet and whimsical, with an undercurrent of a darker reality that grows more evident as Jojo begins to see the real world around him. Its message is pretty simple: Even in the darkest times, kids are still kids, love is more powerful than hate, and Nazis are f-cking morons. The satire is aimed squarely at lampooning fascism, and all of Jojo Rabbit’s sincerity is reserved for the characters with some compassion. Some might balk at making a joke of one of history’s greatest villains, but Jojo Rabbit reminds us that Hitler was a coward worthy of derision. Waititi saves his empathy for a little boy and the women who teach him courage.