Lies and delusions in May December

Inspired by the story of Mary Kay Letourneau and Vili Fualaau, May December is Todd Haynes’ latest exploration of the outer bounds of the world of women. Longtime Haynes collaborator Julianne Moore stars as Gracie, a fifty-something woman married to Joe (Charles Melton), a noticeably younger man. The film opens with Gracie and Joe preparing for a cookout at their picturesque waterfront home on the Savannah coast, but instantly we know something is wrong. Gracie stares into the fridge, discordant, dramatic notes blare from the soundtrack (Marcelo Zarvos reworked Michel Legrand’s score for Joseph Losey’s 1971 film The Go-Between for May December). “I don’t think we have enough hotdogs,” she says flatly.

On the one hand, May December is a darkly funny twisted tale of liars and manipulators abusing the people around them for their own gain. On the other hand, though, May December is a stark examination of the long-term effect of said abuse and manipulation. Gracie and Joe’s noticeable age disparity turns out to be more than just an inter-generational love affair—a May December romance—as we learn that Gracie was thirty-six when she met Joe, who was thirteen. Gracie gave birth to their eldest child while in jail for sexual assault, but later married Joe and had two more children with him. Twenty-three years later, Joe is now thirty-six, the same age Gracie was when they met, and their youngest children, twins, are preparing to graduate from high school.

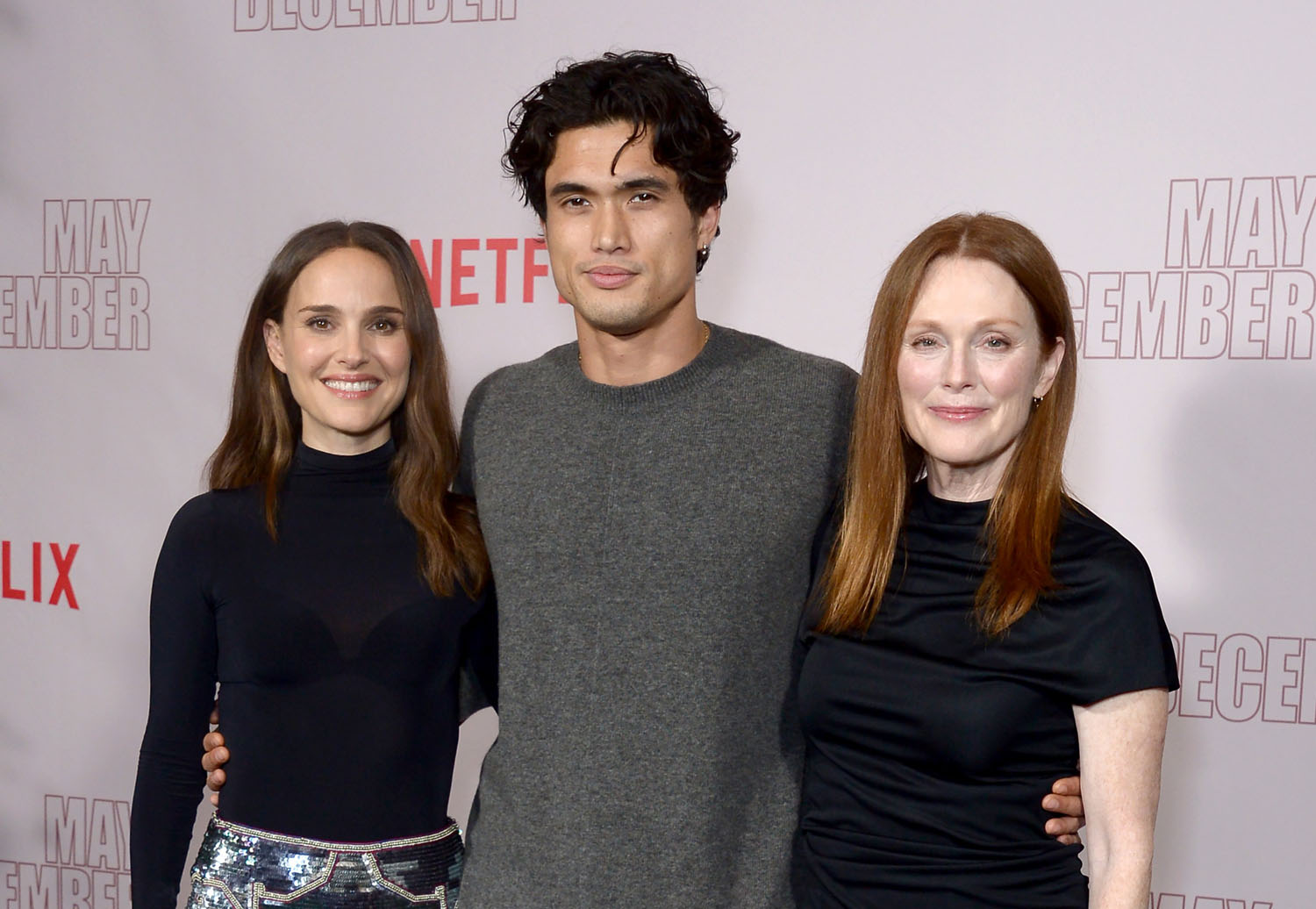

Into this fraught family graduation week comes Elizabeth (Natalie Portman), a famous “television actress” who will play Gracie in a movie about her life. At first, Elizabeth is pleasant enough, obviously trying to be respectful of Gracie and Joe as she interviews the people around them to get a sense of “who Gracie is”. But slowly she begins to morph, changing her clothes, her hairstyle, her preferred lipstick shade to match Gracie. Portman and Moore give brilliantly co-dependent performances, Moore setting the tone as Gracie with Portman absorbing and reflecting her choices like a funhouse mirror.

May December, which is written by Samy Burch, is concerned with manipulators and manipulations, the way we delude ourselves and others. Gracie projects a gentle Southern housewife persona, with soft blonde hair, girlish makeup, and a childish lisp that intensifies when she’s trying to get what she wants. Under the tradwife façade, though, is a manipulator of the first order, body-shaming her daughter into choosing a dress Gracie likes for graduation, body-shaming her son for being “too small” for his age—maybe a symbol of Gracie’s inability to acknowledge the reality of her husband’s shattered childhood, definitely a hallmark of a certain kind of emotionally devastating mother—and treating Joe like her emotional support person, there not to be a partner but to support Gracie in all things. She’s the kind of person who views another person’s misfortune as an inconvenience to her, with little ability to sympathize with others. She is a monster.

But Elizabeth isn’t much better. She’s an emotional vampire, prying apart a family and a community that duct-taped itself back together after a national spotlight turned their lives into a nightmare. Gracie makes it seem like, in the end, she and Joe came through the fire, but as Elizabeth digs into their lives, she finds devastated children and a well of lingering bitterness, intensified by Gracie’s inability to recognize what she did was wrong. Elizabeth is fascinated by the contradictions while ignoring her own, saying the teens auditioning to play Joe in the film aren’t “sexy enough”, or speaking inappropriately to a group of high schoolers about filming sex scenes. She also pretends her intentions are different from any who have come before to tell Gracie’s story, but really, the film is Elizabeth’s chance to elevate her career after being stuck on a successful but cheesy TV show for years.

At the heart of May December is Joe and Charles Melton’s sensitive, heartbreaking performance as man almost completely divorced from himself. Joe obviously loves his children, but he struggles to relate, telling his son, “I don’t know if we’re connecting for if I’m making a bad memory for you.” Joe never got to have a childhood and can’t relate to his teenagers’ experiences, and his whole life is so entrenched in Gracie’s lie that he doesn’t know which end is up. He isn’t prepared for Elizabeth’s flirtations—they’re the same age but he can’t relate to a peer—and he doesn’t recognize when he’s crossing lines, such as inadvertently propositioning an online friend with a shared interest. When it comes to sex and romance, Joe is immature, stuck in a strange arrested development, a mix of suburbanite grill dad and the kid he was when Gracie met him.

Julianne Moore and Natalie Portman are engaged in an emotional cat and mouse that only actors of their caliber could pull off, but it is Charles Melton who defines the film. Joe is going through the motions, always trying to please Gracie, his only honest emotions reserved for his own confusion or his children. Melton walks a fine line capturing the conflict between Joe’s innocence and his devotion to Gracie, or rather, her lies about their life together. And yet Joe is the only brave person in this farce, the one who at least begins questioning reality when the funhouse mirror cracks. May December is wickedly funny on the subject of delusion and the lies we tell ourselves to get what we want, but always there is Joe, the painful reminder of the human cost of those lies and delusions.

May December is now in theaters and will stream exclusively on Netflix from December 1, 2023.