Jimmy O. Yang in Interior Chinatown

There is a moment in the first episode of Interior Chinatown in which the protagonist, Willis Wu goes “not far” to talk with a detective, and it turns out to be a kind of beach party situation like you’d see in an alcohol commercial. Indeed, “Deep Watr” hard seltzer is prominently displayed everywhere, and a sultry voiceover announces, “For those nights you want to go deep.” It’s a pivotal plot point packaged in a parody of a sleazy alcohol commercial, and if the sudden shift in tone and style doesn’t work for you, if the obnoxious techno music and weirdly sexy recitation of nutrition facts doesn’t make you laugh, Interior Chinatown might not be for you.

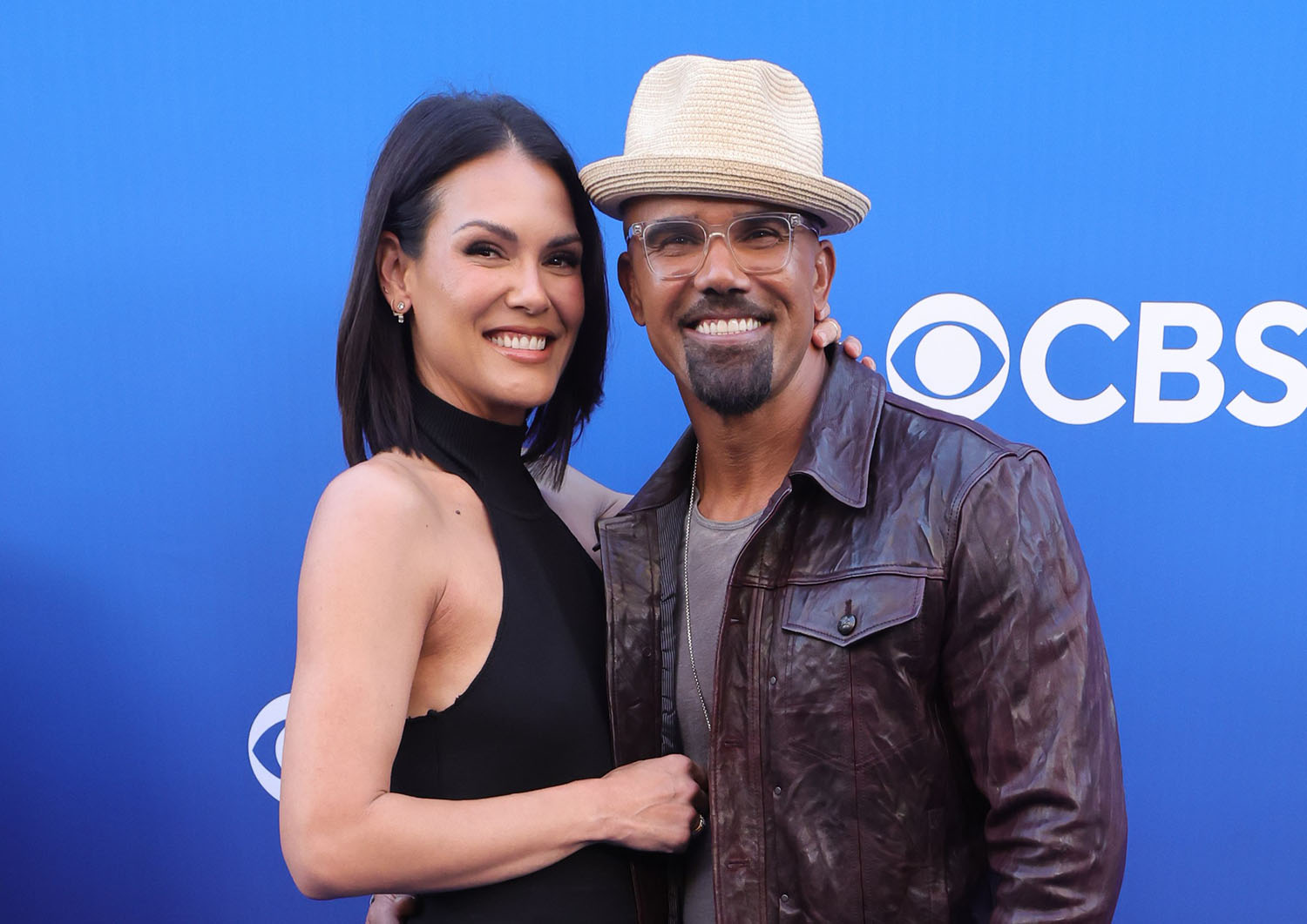

Adapted for television by Charles Yu from his own novel of the same name, Interior Chinatown follows Willis Wu (Jimmy O. Yang) as he attempts to both defy the stereotypes thrust upon him as an Asian-American and solve his brother’s years-long disappearance. Yang shines as Willis, imbuing him with both a sense of longing for more than life as a waiter in his uncle’s restaurant in Chinatown, and a strengthening resolve to finally find out what happened to his brother, a handsome “Kung Fu guy” who inspired everyone around him, but who disappeared amidst one of Chinatown’s gang wars.

Interior Chinatown, which counts Dan Lin and Taika Waititi, who also directs the pilot, among its producers, trades in stereotypes and cliches. The story is essentially split into two intersecting tracks. There is the “real world” of Willis and Chinatown; his missing brother (played with dashing yet cheesy sex appeal by Chris Pang); his grieving mother, Lily (Diana Lin), seeking to turn her life around; and his father, Joe (Tzi Ma), who remains mired in grief more than a decade since his eldest son’s disappearance. Willis wiles away his days waiting tables for his uncle and goofing off with his fellow restaurant worker, Fatty (a superb Ronny Chieng), every day the same. Until one day, he witnesses a kidnapping and finds himself embroiled in an investigation into the never-ending crime in Chinatown.

The other part of Interior Chinatown is, like that fake “Deep Watr” commercial, a parody of police procedurals. Detectives Green (Lisa Gilroy, Jury Duty’s “bones with other bones” lady) and Turner (Sullivan Jones) walk and talk like they’re in a police procedural, cracking jokes over dead bodies and constantly demanding to “enhance” evidence. Whenever they show up, the lighting changes, shifting from the warm orange and yellow tones of the “real” world to a cold blue common to procedurals of a certain era. With the detectives is Lana Lee (Chloe Bennet), a “Chinatown expert” by dint of being Asian-American, though she does not live in Chinatown, and is in fact, not familiar with it at all. Enter Willis, who becomes her man on the inside, supplying her with information and tips about the neighborhood.

The tonal shifts add a layer of style to Interior Chinatown and give Yu and the series writers plenty of opportunities to explore various stereotypes thrust upon Asian characters—Lana Lee, for instance, is a “perpetual sidekick”—but the extremely meta tone of the series might not work for everyone. More, with only five out of ten episodes available for review, it’s impossible to tell if this construct is going anywhere. The longer Willis intrudes on the procedural world, the more it breaks down, which is interesting, but without being able to see how it pays off, I can’t say for sure if the construct ultimately serves the narrative. It’s certainly an interesting idea, and it sets up some good jokes in the first half of the series.

A bigger issue for the series, frankly, is that the central mystery isn’t that compelling. Worse, it feels stretched out so that episodes feel long, even slow. The point of Interior Chinatown isn’t really the mystery, it’s how Willis navigates the stereotypes and assumptions he faces as an Asian man, but Interior Chinatown is ten episodes long, and episodes run 40-50 minutes each. That’s a lot of time to fill, and it would be nice if the mystery were more compelling in and of itself, to match the cleverness of Yu’s intersectional plot devices.

There are a lot of enjoyable performances in Interior Chinatown, and the crisscrossing styles give it flair, but episodes feel bloated, at least in the first half of the season. The second half might be a downhill sprint to the conclusion, but then we’d have a balance problem. Any way you slice it, the weakness of central mystery undercuts the series’ bigger ambitions. But it is certainly ambitious, with a layered meta concept that demands attention. You can miss specifics regarding the mystery and never feel lost, but if you miss a cue when the story switches between meta contexts, you might wonder why everything is suddenly sort of goofy and cheesy, especially since there is no overt explanation about what is going on, the shifts between concepts are all in the context clues and lighting cues. Interior Chinatown has a lot to say about stereotypes, I just wish it also offered a good mystery to solve.

Interior Chinatown is now streaming all episodes on Hulu.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ndzygetBHV0