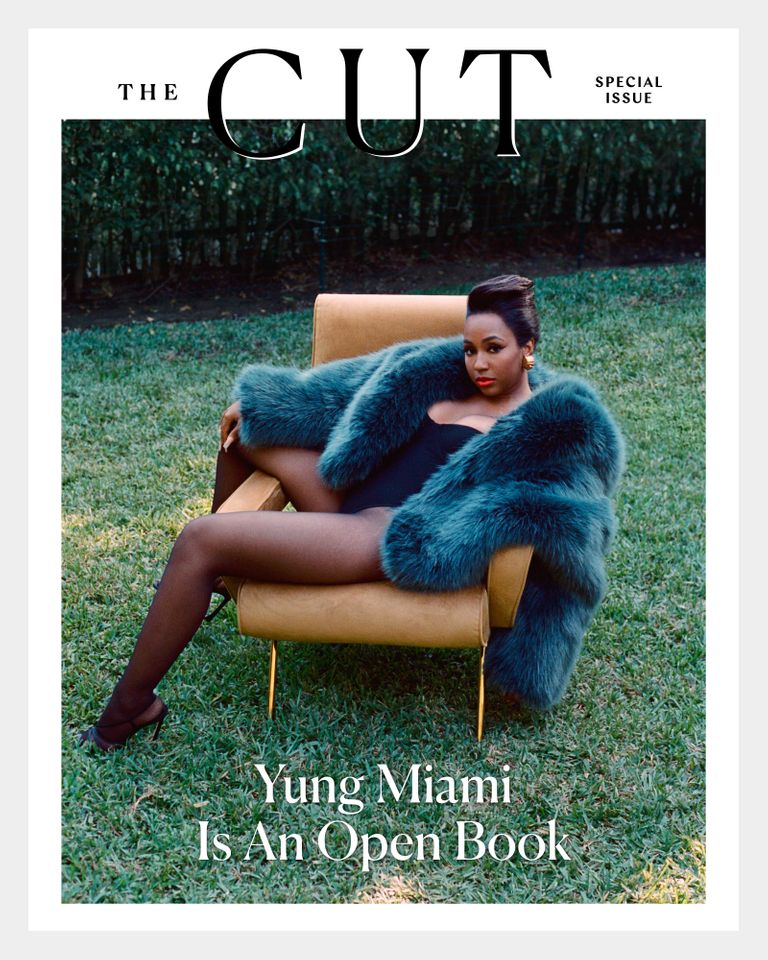

It's Yung Miami's time to speak

Caresha Brownlee, better known as Yung Miami, was The Cut’s April cover story. And Megan Thee Stallion covers ELLE with a first-person essay chronicling her journey to healing after being shot by Tory Lanez. The two stories, despite being wildly different in nature, share overarching themes that speak to what it’s like to be a Black woman in society, but also what it means to be a famous Black woman in society. Both women, in their own way, touched on things like the loss of privacy that comes with being a celebrity and how that unfolds when you’re dealing with trauma, their relationships with their mothers, and the idea of being more than what they’re made out to be in the media.

While the decision to feature Meg in ELLE is a no-brainer, the decision to feature Yung Miami as the April Cut cover story is interesting, because she’s featured without her City Girls counterpart JT. Despite the pair being featured in Vogue and Variety, this solo cover story is a bit of a new direction for her.

And Yung Miami didn’t hold back – not that she ever does. She touched on everything from the death of her children’s father three years ago to her situationship with P. Diddy and her desire to change the way she talks out of the fear of being perceived as illiterate.

Despite the backdrop of the interview being in Yung Miami’s home, filled with luxe goods and furnishings and symbols of wealth throughout, she describes humble beginnings and getting her celebrity start from being “hood famous”. But even after launching to fame with JT, she was still dealing with the reality of growing up in the hood.

In 2020, the year that her son’s dad, Jai Wiggins, died, gun homicides across the U.S. rose 33%. The increase disproportionately affected Black Americans who, despite making up only 14% of the U.S. population, accounted for nearly half of the nation’s homicide victims, according to FBI data released in the fall of 2021. Processing George Floyd’s very public killing was impossible for so many Black people, and for her to have lost someone so close to her after such a public display of racism, colonialism and police brutality must have impacted her in indescribable ways. But sadly, Yung Miami’s reality is one shared by so many women.

She described processing Jai’s death and having to do that privately despite being a public figure – and it’s moments like these that her and Megan’s stories intertwine. Both women were dealing with gun violence in 2020, a year that was already so difficult to navigate.

As she discussed breaking into acting, snagging a role in Kenya Barris’ You People, she went on to talk about getting a role in the BMF television series and how triggering it was for her.

“In real life, my baby father got killed,” she said. “I always say I never got a chance to go through the emotion of my baby father getting killed and feel he’s gone because I was always working, which was a good thing because it kept my mind off of it.”

Megan touched on this in her ELLE essay, lamenting over the fact that she didn’t get to process being shot in private – and how the assumption was that she was fine because she was still making music and performing and doing what she had to. Both women also talked about their moms. For Megan, she briefly touched on needing the guidance and reassurance from women like her mom and great-grandmother in the most difficult ordeal of her life. And Yung Miami described her closeness with her mom, who she views as a “mom, a friend, and a sister all in one,” saying that she feels like she owes her a lot for what she sacrificed to give her a good life. She went on to add that becoming a mother herself has taught her patience.

When Megan’s interview was published, there were certain excerpts that really seemed to resonate with people. And I agree with Lainey about not excerpting – they’re her words and they’re there for you to read. But most of the Black women on my timeline seemed to really connect to her mention of not having the look of a typical victim, and therefore not being offered the support that likely would’ve flooded in for someone smaller, lighter, or a woman that wasn’t a rapper.

Yung Miami also discussed figuring things, and herself out, describing her openness about sex on her popular podcast, Caresha, Please. When she revealed she’d participated in golden showers before, the internet went nuts. But she didn’t shy away from the conversation when it came up, even forcing the writer to say it, rather than just allude to it.

“Sex is a part of life. I’m grown, and maybe I talk about it too much, but everybody’s got their personal experiences…If we grown and we in the house just chilling and want to talk about sex, what’s wrong with that?”

Hearing her speak so candidly not only about enjoying sex but talking about it too, as she frequently does on her podcast, is refreshing, because historically, Black women’s sexuality and their enjoyment of it has been policed. Last year, I wrote about Chloe Bailey navigating the difficult terrain of stepping into her sexuality in the public eye, which she touched on in many interviews, including this one, where she had this to say:

“No matter what women do, no matter how talented we are, no matter how screwed on our head is, someone will always have a problem because we choose to celebrate our body and the skin that we’re in.”

These interviews – Megan’s, Yung Miami’s, and even Chloe’s, really highlight the multifaceted nature of being a Black woman. The impact of these stories from two of the heaviest hitters in the world of Black women rappers being published in these specific outlets, touching on things like privacy, code-switching, vulnerability, safety and mental health breathes life into what Black women have been saying this whole time. We are more than how we talk. We are more than how the media portrays us. We are more than the music we make or the things we create. We are unapologetic. We can be all of these things, and we can be them at the same time. And we deserve to be believed and we deserve to be protected.