Inside Out is amazing

At one point in Inside Out, Pixar’s latest after a two year hiatus, the anthropomorphized emotions inside a little girl’s head spill boxes of fact and opinions and, unable to tell them apart, jumble them up while putting them back. “Don’t worry,” says the little girl’s imaginary friend, “it happens all the time.” It’s as surreal a moment as has ever been in a Pixar movie, which includes a scene of two robots dancing in space, and yet it’s so grounded it sails by with barely a shrug. That it’s a clever joke is actually secondary to how smoothly that moment passes, the abstract environment of the movie is rendered so well and so consistently. Like the best Pixar movies, Inside Out is ambitious and clever, full of perfectly structured jokes and heartfelt moments that challenge even the most cynical among us to find fault.

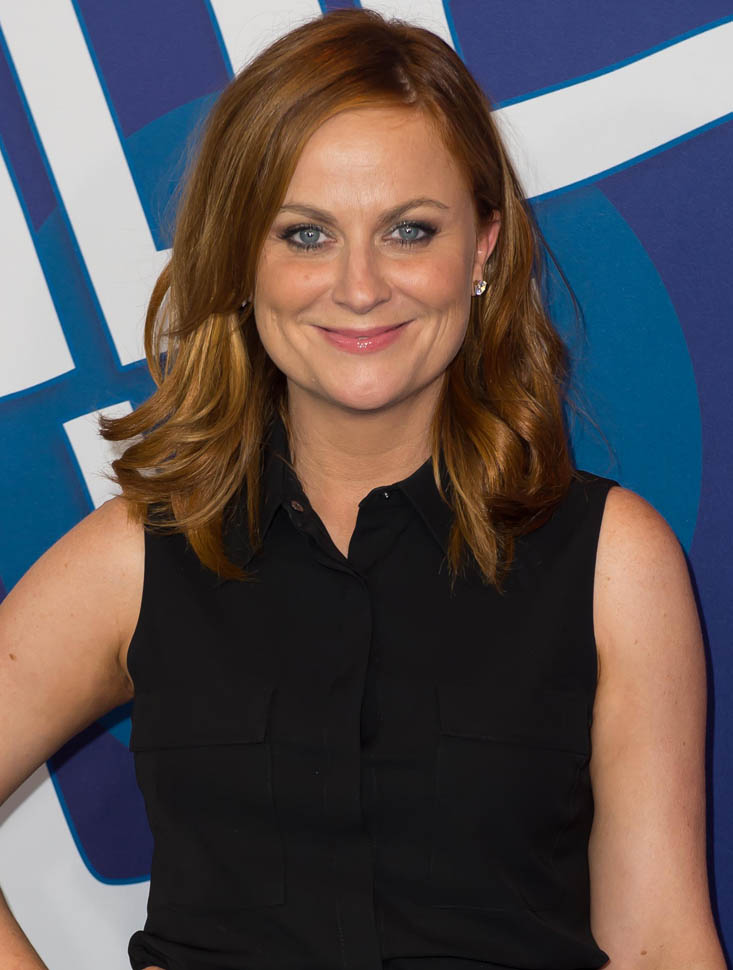

Taking place inside the mind of an eleven year old girl, Riley, Inside Out stars emotions, led by Joy (Amy Poehler) and Sadness (Phyllis Smith). Joy and Sadness are joined in the “headquarters” by Anger (Lewis Black), Disgust (Mindy Kaling), and Fear (Bill Hader, the least recognizable of the vocal cast), and together the emotions “control” Riley as she navigates a tumultuous move across the country. For small children, Inside Out works as just a story of colorful characters on a quest, with simple comedy moments and adventure thrills, but the older you get, the better Inside Out plays. The message is geared toward children, naturally, and it’s a good one—it’s okay to feel sad sometimes. But Inside Out also works as a parable of growing up, as well as an allegory for depression.

Joy exerts the most control over Riley, doing her best to ensure that Riley is always happy. This means that she literally sidelines Sadness, keeping her as far away from the controls as possible. However, after Riley moves, suddenly Sadness can’t help but touch memories, making them sad. In an effort to prevent Sadness from “ruining” Riley’s personality-determining core memories—all of which were formed pre-move—Joy leaves the headquarters and, along with Sadness, becomes lost in Riley’s memory banks. With Joy and Sadness out of HQ, Anger, Fear, and Disgust try their best to control Riley, but the kid’s “personality islands” begin breaking down until they realize that without Joy and Sadness, Riley risks not being able to feel at all.

There is so much cleverness tucked into Inside Out, from the constantly changing headlines on Anger’s newspaper to a Chinatown joke no one else in the theater got, and it will likely work in different ways for different people. The kids in the audience when I saw it reacted most to the loss of Riley’s imaginary friend and also the saddening of her memories, but adults seemed split between the metaphor for growing up—with Joy and Sadness returned, Riley begins forming more complex memories that contain multiple emotions—and the allusions to depression as more and more of Riley’s emotional core is shut down. But it works equally well on all those levels, it’s just going to depend on what kind of baggage you bring to it.

The only ding on the movie is that, for the first time, Pixar has made a movie that blatantly plays better for adults than it does for kids. Too many of the jokes were aimed at the grown-ups in the audience, and the movie gets a little too abstract in places for kids to follow. One scene is literally about abstract thought and you can feel the children in the audience spacing out during that sequence. Inside Out is arguably the best film Pixar has ever made, but ask an eight year old what their favorite Pixar movie is, I doubt many would actually pick Inside Out. (The answer is always Wall-E.) Given the overall accomplishment of the film, though, that’s a minor complaint. If a kid didn’t quite get it initially, she will come to understand it more and more as she grows up. That’s Inside Out’s greatest achievement—it’s a children’s film that won’t have to be viewed through a lens of nostalgia, but one that can be re-engaged with on an entirely new level as an adult.