Joel Edgerton’s The Gift

So you know how I was just recently saying that actor-directors are usually bad? Well, funny thing, Joel Edgerton just released his directorial debut, The Gift, and it’s really good. So while yes, fewer actors should become directors, Joel Edgerton gets a pass because he is actually good at it. Edgerton not only directs The Gift, he also wrote it, and he stars in it, which would normally scream “vanity project”, but in this case Edgerton clearly had a story he wanted to tell—it’s not about making him look good. The uniformly terrible trailers are wildly misleading and this is not a cheapo creepy house horror movie like they make it seem. There’s a lot more going on in The Gift.

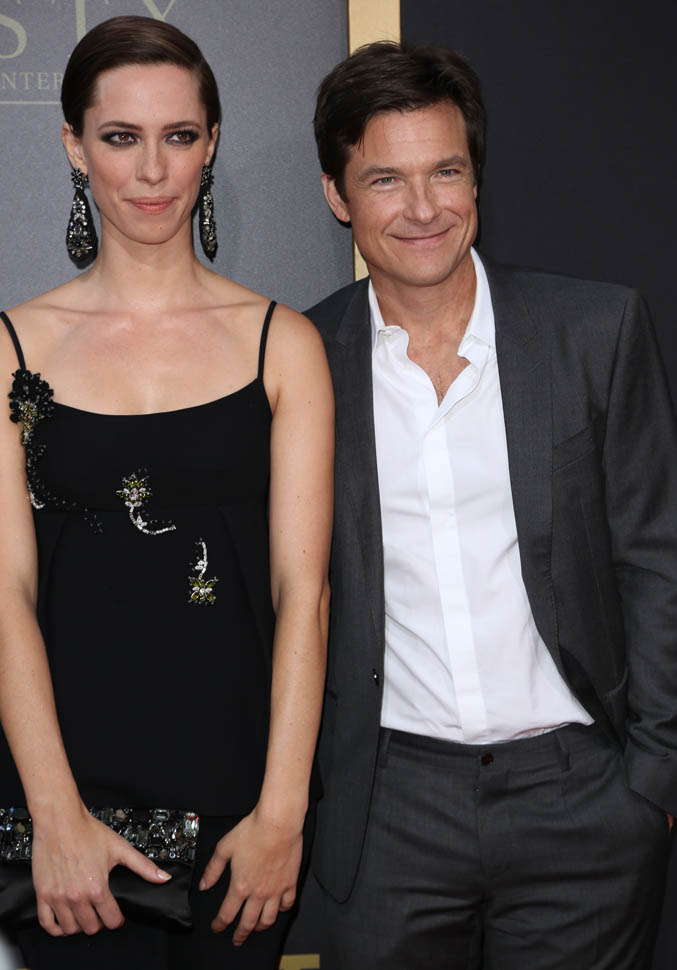

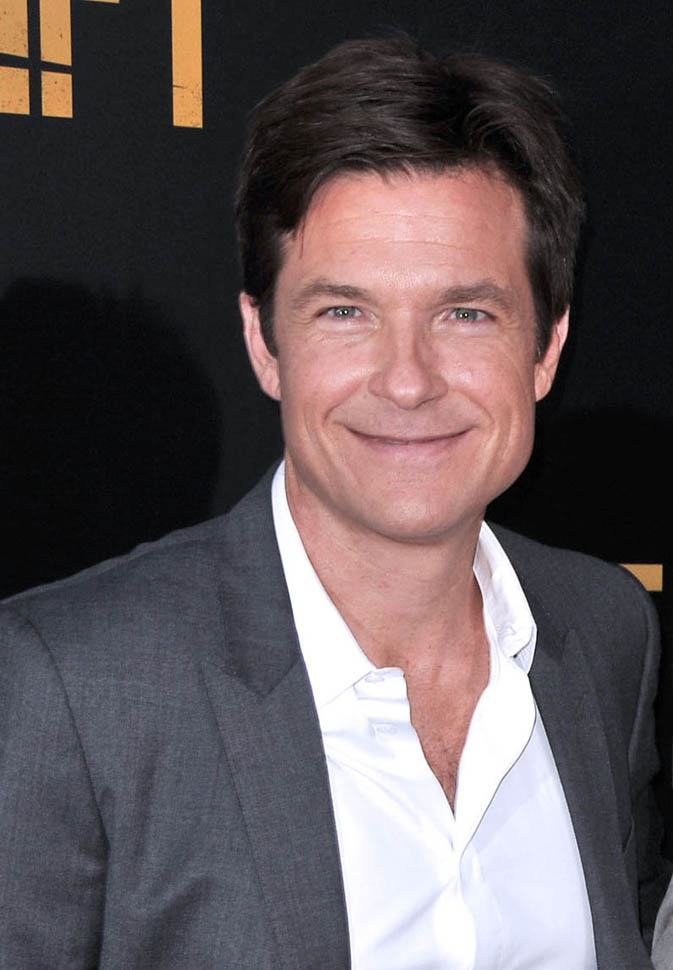

This looks like an easy paycheck for Jason Bateman, but no, he is in this movie specifically because he is Jason Bateman. We have certain expectations of Bateman as a protagonist, and Edgerton leans into that, playing on Bateman’s on-screen persona and our expectations for him as a protagonist. He stars as Simon, who along with his wife, Robyn (Rebecca Hall), has just moved back to Los Angeles after a long sojourn in Chicago. Hall hasn’t really done much for me post-The Town, but here she’s very good. Robyn is lonely and fragile, thanks to an alluded-to event in Chicago that was probably a miscarriage, and Hall captures her nerves and tension perfectly. Edgerton rounds out the main cast as Gordo, a hugely off-putting weirdo aptly dubbed “Gordo the Weirdo”.

I noted in my review of Before We Go that Chris Evans doesn’t really have a handle on the visual language of film—well Joel Edgerton does. Where he places his camera is critically important—what we DON’T see is often more important than what we do. He understands how costuming and props contribute to character as well, and his writing is efficient and displays the same kind of narrative chiaroscuro he uses in his scene construction. The Gift is a psychological thriller, and Edgerton manages the tension throughout the film beautifully, steadily ratcheting it up with his use of perspective. We don’t always see what the characters see, which lets us in on certain secrets while we wait anxiously for the characters to catch up, but in other cases it leaves things up to our imaginations, which is way worse than anything you could put on screen.

Which is why we now need to get into some spoilers, because that ambiguity has opened a can of worms. If you don’t want to know anything more about this movie, this is where you get off.

…

…

…

Simon and Gordo’s toxic past, and Gordo’s desire for revenge, come to a head in the finale when Gordo shows Simon a recording in which it is heavily implied that Gordo drugged and raped Robyn, and that Simon’s newborn child might not even be his. It’s a gut-punch moment, the culmination of eighty minutes of carefully built dread, and as it played out I knew some people would absolutely hate it. Count The Mary Sue among those who do not like it (you can read their assessment here), but for me, that ending worked.

Robyn is a sympathetic character, but she is never driving the narrative—Gordo is. Robyn is always a pawn between the two men, they both lie to and manipulate her. She’s victimized throughout the movie, by Gordo’s stalking and Simon’s insidious control. It’s a credit to Edgerton’s writing and Hall’s performance that we like Robyn so much we don’t want to see bad things happen to her, but the entire movie is bad things happening to Robyn, and they steadily escalate until The Worst thing happens. Or maybe it doesn’t—WE DON’T ACTUALLY KNOW WHAT HAPPENED.

Edgerton leaves it vague in a way that borders exploitative, because it seems to reduce humiliation to pure shock value. But the ambiguity of that scene plays into the film’s theme of never really knowing the things you think you know. Good, bad, persecutor, victim—these are all defined by one’s perspective, a perspective that Edgerton purposefully skews. The entire point of The Gift is the not knowing. Is Gordo really that twisted and cruel? Or did he just find the perfect way to torture Simon, forever? It’s up to each individual viewer to decide, and there is no right answer. It’s an ambitious gambit on Edgerton’s part, but it’s one that simply won’t work for everyone.