Kingsman: The Secret Service review

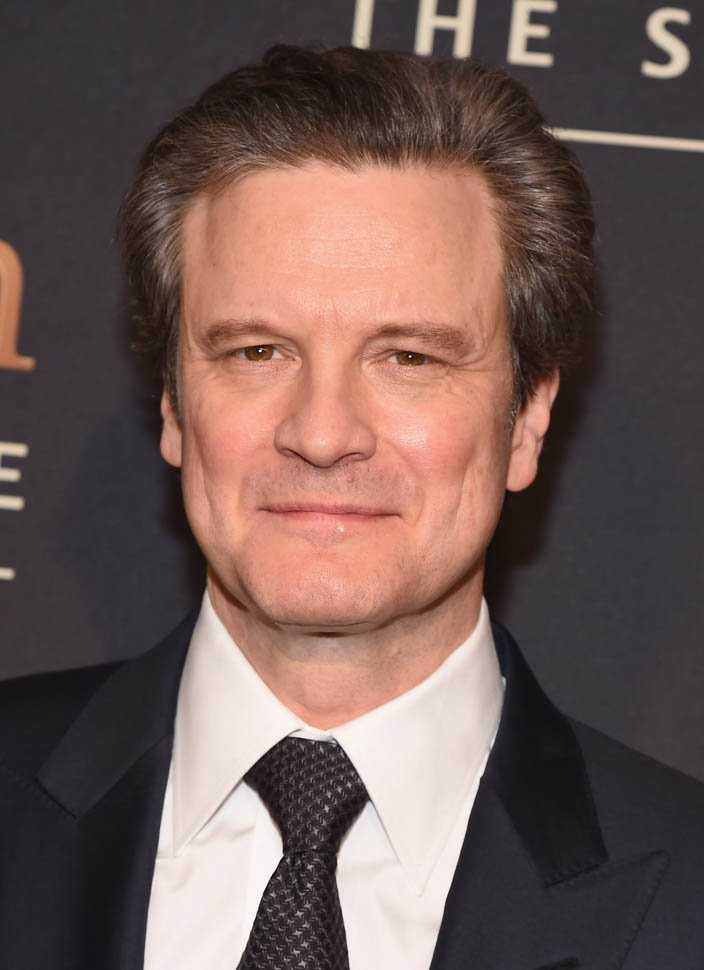

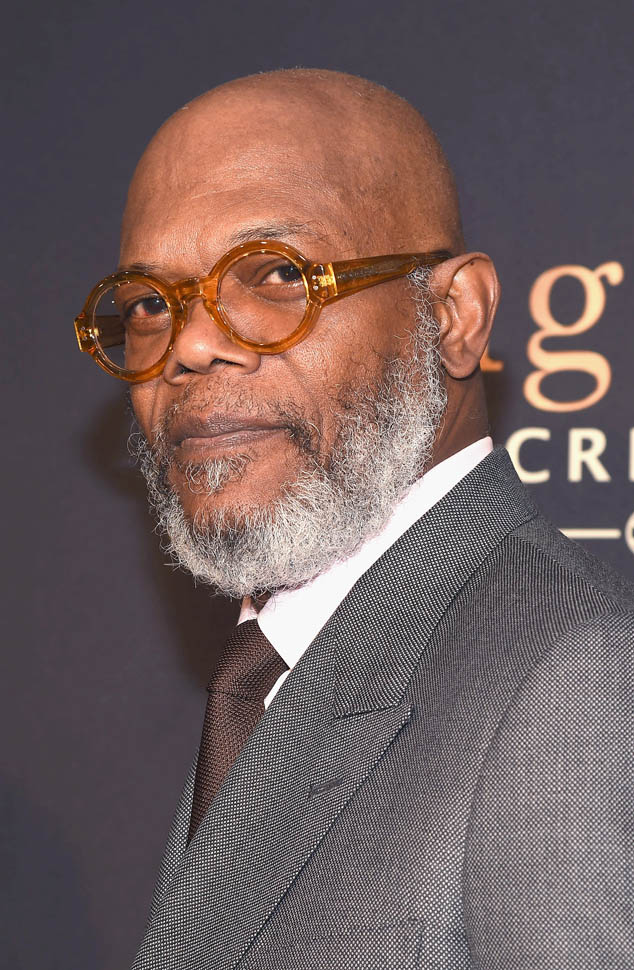

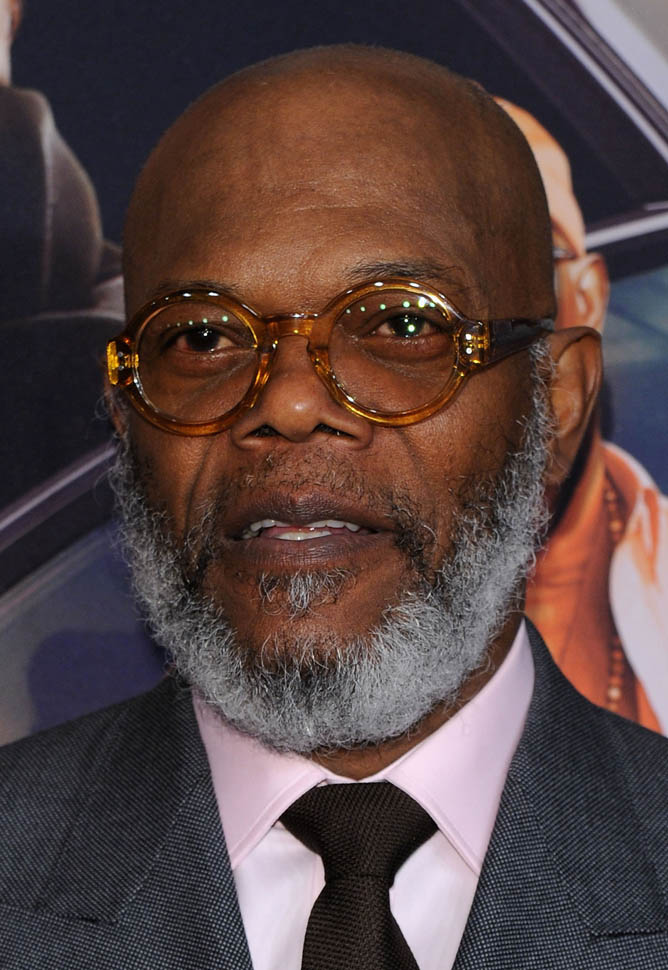

There’s a scene in Kingsman: The Secret Service (why the subtitle? It’s dumb) in which Colin Firth, as dapper gentleman spy Harry and Samuel L. Jackson as megalomaniac Valentine, talk about their love of old spy movies, bemoaning that modern spy thrillers have “grown too serious”. It’s meta and would normally be obnoxious, but Jackson and Firth handle it with such wit that it comes off as a slick wink to the audience while also serving the movie’s plot. That’s not an easy line to walk, but Kingsman manages to skate over a number of tricky concepts with style and aplomb—right up until it doesn’t.

Directed by Matthew Vaughn (X-Men: First Class), Kingsman is set in the modern day but it owes a lot to the James Bond movies of the early 1960s (ground that The Man from U.N.C.L.E. will also tread later this year). It’s a pitch-perfect combination of old-school gadgetry, Machiavellian plots, and Tarantino-esque violence. That’s not an easy combination, which is why the Bond franchise eventually had to shift gears and become more grounded and realistic. Audiences don’t necessarily want everything to be gritty and dark these days—I would argue the exact opposite, actually—but realism is important to contemporary audiences. It’s a by-product of special effects sucking the magic out of movie magic—because we can now make anything look real, we want everything to look REAL.

Audiences have never been savvier than they are right now, and it’s harder than ever to trick an audience into embracing something that is patently unreal, and yet, Kingsman does it charmingly. It does so by giving us believable characters within the heightened, Spy vs. Spy world of the “Kingsman”, an international spy organization that doesn’t seem to answer to any one government and somehow isn’t pluralized even though it’s a group of people and not just one guy. The Kingsmans’ headquarters is absurdly high-tech and there are old-fashioned movie spy gadgets like poison pens and cigarette lighter grenades all over the place, but it’s all handled by grounded characters.

Firth stars as Harry Hart, a Kingsman agent who grows concerned when a fellow agent dies while trying to rescue a kidnapped professor who turns out not to be kidnapped at all. While Harry is trying to unravel this mystery, the Kingsmans—this is a plural nightmare, someone help me—have to replace their fallen agent. Enter Eggsy, Harry’s protégé. Where Harry is elegant and posh, Eggsy is straight out of the London council flat where they made Attack the Block. He’s washed out of everything that’s ever mattered in life, has no prospects, and is very, very angry. He also has no father, because his dad died on a previous Kingsman mission. Harry feels responsible for Eggsy, because it was his screw-up that resulted in Eggsy’s dad dying.

Firth and the relatively new Taron Egerton—who is a real find—as Eggsy have enough chemistry to carry off the mentor/mentee relationship which is the heart of the movie. (I really appreciated that this movie didn’t have a love interest.) Kingsman has a very-not-subtle opinion on class relations, which are enacted by Eggsy and his fellow Kingsman trainees, all of whom are posh. This movie has no subtlety—Harry gives a speech about the changing times that would be eye-roll inducing if anyone other than Firth were delivering it—but the combination of talented actors and Vaughn’s breezy direction doesn’t allow the movie to get bogged down by its own ham-handedness.

SPOILER TERRITORY

Until the end, that is. I was 100% with Kingsman—it’s got enough style and cleverness to propel it, and the action sequences are A++—but then it went for a crude, crass joke right at the end that dimmed my enjoyment. As Eggsy is racing to save the world, an imprisoned female character says that if he does, in fact, save the world, they can “do it in the assh*le”. Eggsy bargains for a kiss, she offers butt stuff, and while it’s not the best joke, it plays, if a bit tinny, in that moment. But then they revisit it. I mean, they REVISIT it. This is not the most feminist movie, but it does feature two female characters, Roxy and Gazelle, who are not objectified by their male counterparts. Kingsman is quite refreshing in this regard, but then Vaughn, who co-wrote the script with Jane Goldman, throws it away for a cheap joke about anal sex. It’s completely objectifying and vulgar, especially since Kingsman went for smarter jokes than that for the other 128 of its 129 minute run time. A disappointing final note for a movie that is otherwise entertaining.