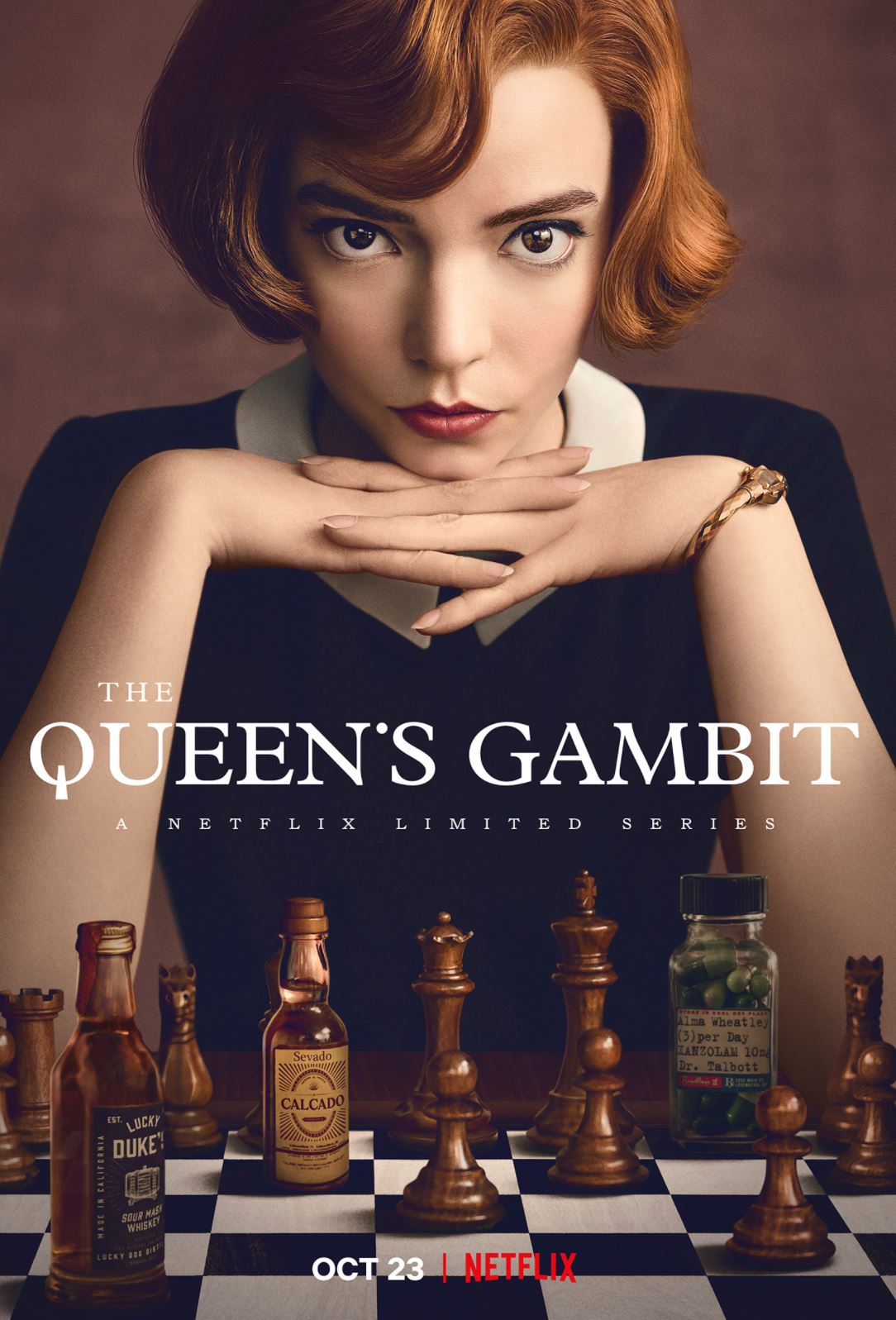

Anya Taylor-Joy in The Queen’s Gambit

There is a certain type of character who appears in television shows, you know her when you see her: a lead character, pretty, almost always white, and the object of every other character’s fascination and sexual desire. She is interesting! So charming! A marvel! The show will insist this character is the most intriguing and wildly desirable character on screen, even though she is frequently upstaged by supporting characters, because this character often has no grounding interest or real personality. She is fascinating only because the story needs her to be. I call her the “magnetic woman”, a character with the gravitational pull of the sun, but one that is never as interesting or desirable as the writing insists. Examples of magnetic women include Rory Gilmore, Rachel Green, Midge Maisel, and more recently, Emily in Paris’s Emily Cooper. (Lainey: I have one more! Serena van der Woodsen!) The Queen’s Gambit, the Netflix limited series of the moment, is notable because it features a magnetic woman but one who actually deserves all the attention heaped upon her.

Played with doe-eyed intensity by Anya Taylor-Joy, Beth Harmon is a chess prodigy in the 1960s who bursts onto the chess scene in Kentucky and ends up playing grandmasters in the USSR. Beth is a classic magnetic woman: everyone who meets her falls under her spell and every man she meets loves her (as do some of the women). But Beth Harmon isn’t some milquetoast character with no personality, she is a bona fide genius with a rare talent that takes her to the upper echelon of international competition, and she is also a goddamn mess. The Queen’s Gambit, adapted from Walter Tevis’s novel, deconstructs the magnetic woman trope by both justifying Beth’s specialness and exposing her flaws.

Orphaned at eight, Beth spends part of her childhood at an orphanage (she is played at this stage by Isla Johnston). There, she learns to play chess from the janitor, Mr. Shaibel (Bill Camp), in the dark, dingy basement. Director Scott Frank (who also directed the Western Godless) stages those basement lessons with an almost hilarious sense of dread, as if at any moment these scenes could take a turn toward something ugly and predatory. Mr. Shaibel cares for Beth, but he knows that she’s “got [her] gift, and what it costs”. He seems genuinely concerned with what price the universe will extract from this sullen, angry young girl with a monumental talent. The Queen’s Gambit itself is also concerned with this, being as much about “the cost” of Beth’s gift as the gift itself. This is one of the ways in which it deals with Beth as a magnetic woman, by saddling her with problems which have consequences.

Her chief problem is substance abuse, which begins with the tranquilizers doled out to the orphans. Her drug dependency begins at the same time she discovers chess, for which she has an intuitive talent, and so the two become inextricably linked in her mind. Alcohol comes later, a crutch for social situations for which her chess-focused childhood has left her ill-prepared. And she has as her enabler her adopted mother, Mrs. Wheatley (Marielle Heller), herself a talented woman stifled by midcentury housewife life. For the first half of its episodes, The Queen’s Gambit seems like it’s going to be about the link between madness and genius, but in the later episodes, it begins unwinding Beth’s addiction and the leftover trauma from her childhood and the legacy of her unwell birth mother. In order to fully embody her genius, Beth must confront her problems, a lesson almost no other magnetic woman has ever learned.

As for the men she sucks up her in wake, there is Harry (Harry Melling), the state champion she decimates in her first tournament; Townes (Jacob Fortune-Lloyd), another local player and reporter; and Benny Watts (Thomas Brodie-Sangster), a fellow prodigy and champion; there is also a dalliance with French model Cleo (Millie Brady). Yes, pretty much everyone Beth meets is infatuated with her, but she is once-in-a-generation gifted. Everyone is touched by her genius, whether they remember her as a friend, a fellow player, or a lover, or both. The trope of the magnetic woman is much more tolerable in The Queen’s Gambit because Beth possesses a truly rare gift, which makes her worth noticing. Also, at the height of her addiction she is a crappy person, and there are consequences to her behavior, both professional and personal. The Queen’s Gambit does not let Beth off the hook just because she’s a genius.

Magnetic women aren’t usually required to learn and grow. The script they’re in will insist they are perfect in all their bland glory, that being a beautiful protagonist is all it takes to hold the screen. The Queen’s Gambit is not so simple. Beth is a mess of contradictions, in some ways lucky, in other ways cursed. She is the walking embodiment of the myth of Two Wolves, and the dramatic tension of the series isn’t about her romantic entanglements or even her chess career, it’s about whether or not she can overcome her demons and become the once-in-a-lifetime player Mr. Shaibel saw in her as a child. You don’t have to care about chess to enjoy The Queen’s Gambit—though the chess matches are enthralling even for the uninitiated—because the series is stylish and entertaining, as engrossing as Beth. She is the rare magnetic woman who actually is as fascinating as the story insists.

The Queen’s Gambit is now streaming on Netflix.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CDrieqwSdgI