Women, grief, and horses in East of Wall

There is an inherent skepticism when an outsider tells a particular community’s story, that they will in some fundamental way misrepresent or misunderstand the world they’re depicting, or worse, commit an act of socio-emotional tourism—poverty p-rn is among the worst of these. Take billionaire Nicola Peltz-Beckham’s wildly misguided film, Lola, which she wrote, directed, and starred in, portraying an exotic dancer and addict struggling to raise herself and her little brother out of poverty. Lola is everything wrong with outside-in views on communities stricken by generational poverty, addiction cycles, and trauma. But the other side of the coin is when artists keyed into the humanity around them peer into spaces that mainstream art often overlook, and there you can find sensitive, humanist portrayals of marginalized people and communities.

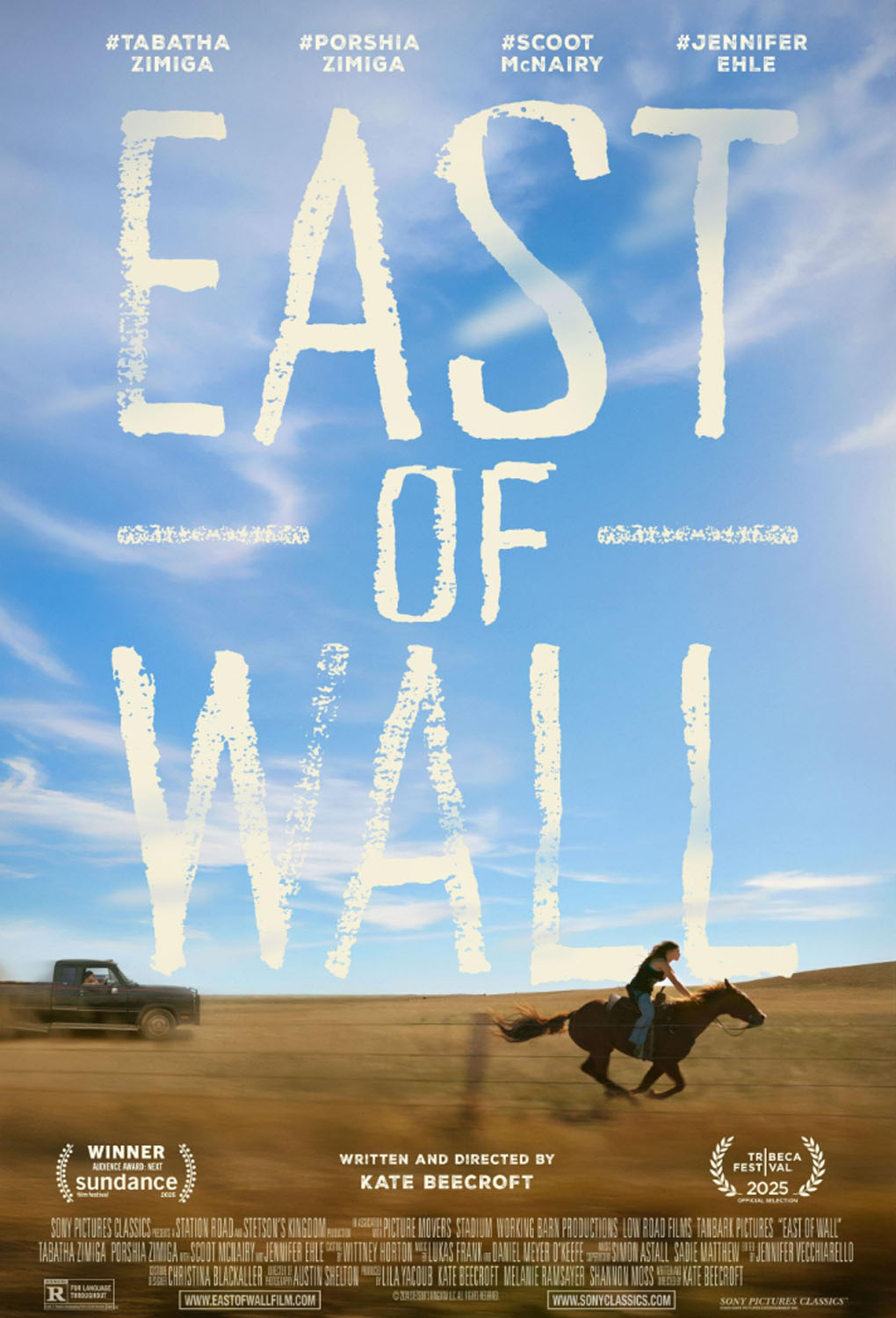

Such is the case with Kate Beecroft’s feature film debut, East of Wall. Beecroft spent three years in South Dakota, where she met the Zimiga family, which was sundered by loss, grief, and subsistence ranching. Written and directed by Beecroft, East of Wall stars Tabatha Zimiga and her daughter, Porshia Zimiga, as fictionalized versions of themselves, a mother-daughter pair trying to keep their horse ranch afloat after Tabatha’s husband died by suicide (and she had to clean it up).

Beecroft’s work most starkly reflects Chloe Zhao’s own trip into South Dakota to make her earliest films, Songs My Brothers Taught Me and particularly The Rider, which also stars a real-life family portraying themselves and is set in the world of South Dakota horses and rodeo. Like Zhao before her, Beecroft is attuned to the small details of rural life, from the combination of stunning, if stark, natural beauty, to the detritus of a failed society. The Zimigas have been left to fend for themselves in every way, and Tabatha’s way of attempting to break the cycles of trauma, poverty, and abuse around her is by welcoming every stray kid in the county in the hopes of providing them with a safe home and some life skills.

Tabatha, with her tattoos and undercut, is a striking figure herself, steely and resolved. Porshia is her wild, angry counterpart, their grief mutual but not effectively shared. The mother and daughter seem only to have horses in common—Tabatha trains them, Porshia rides them, and together they market and sell them on TikTok. But business is slipping, prices for the Zimigas’ prize-winning horses dropping, which leaves them scrambling to afford their ranch. Enter Roy, portrayed by Scott McNairy, one of the few professional actors in the film. He wants to buy Tabatha’s ranch but leave her in charge of the horse training business, a deal that seems too good to be true. Burned by life one too many times, Tabatha is appropriately wary of his offer.

So, too, is Tabatha’s mother, Tracey. Jennifer Ehle plays Tracey with enough grit to believably have produced Tabatha, even though Ehle is a classically trained British actor from an acting family. Brits usually struggle playing working class Americans, let alone poor rural Americans, but Ehle slips past almost unnoticed. One of the most effective scenes in the film is Tracey’s sideways monologue to Roy about not cheating her daughter and granddaughter, a distillation of one of the film’s central themes, of how women are forced to act as janitors to the men around them, cleaning up their messes both figurative and literal.

East of Wall looks great, Beecroft’s direction aided by cinematographer Austin Shelton. They capture the American west with a combination of romance and weariness. It’s a beautiful place, but it’s also a place of endemic poverty, high suicide rates, and drug addiction. East of Wall never sinks to the level of poverty p-rn, though, mainly because the Zimigas are never set up as analogs for anything greater than themselves, and Beecroft’s focus is squarely on the mother-daughter pair and their relationship. By staying close to the human stakes of the story, Beecroft keeps East of Wall within the bounds of humanist cinema.

The script is the primary weakness of the film, though. Perhaps Beecroft didn’t want to dictate too much how the Zimigas present themselves on screen, but the end result is that East of Wall is a little meandering and not as structurally tight as it could have been. But that is a relatively minor complaint, especially as Tabatha and Porshia so effectively embody a fractured maternal relationship seeking an even keel. East of Wall is a lovely film about a mother and a daughter struggling to keep it together through devastating grief, with a side helping of horses.

East of Wall is now playing exclusively in theaters.