Loan Tran, a.k.a Kelly Marie

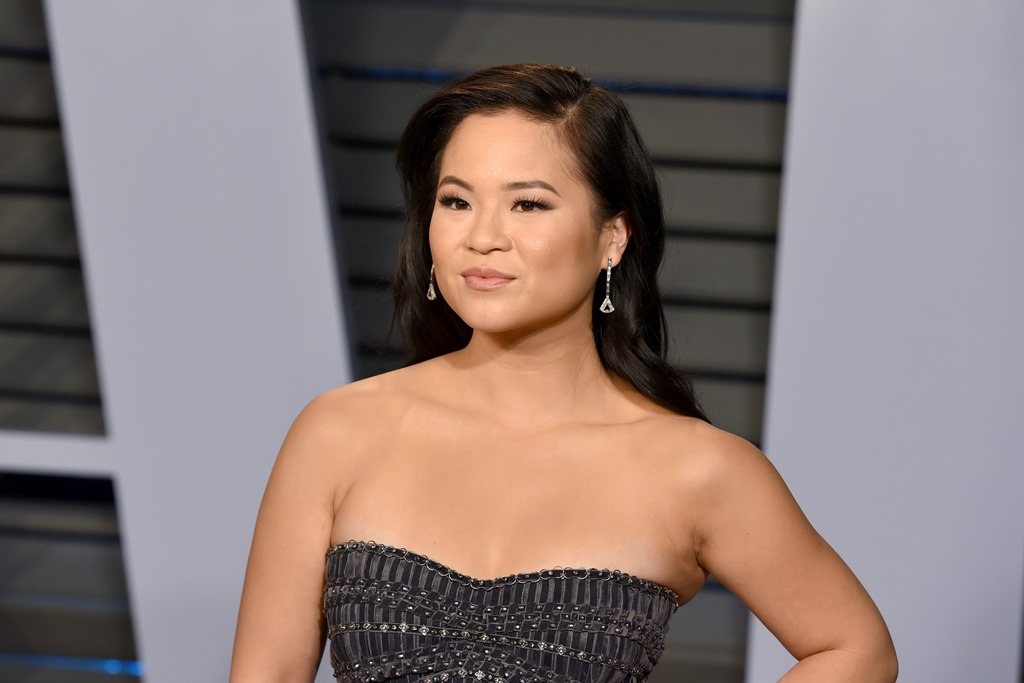

Even if you don’t follow Star Wars, even if you tune out any headline that includes the words ‘social media’, you heard about Kelly Marie Tran. That she quit social media after she was bullied and berated by Star Wars truther bros for daring to appear in their beloved franchise without filling all their supposed requirements, like being white, stick thin, and essentially, there for decoration.

What, you think I’m editorializing? I am. But it’s partly because I’m mad at the way people are dancing around the story. Tran released a statement today, and some of the news articles are dancing around it even as they print it – one even said that when she deleted her social media, ‘nobody knew why’.

This, of course, is bullsh-t. Everyone knew why. But today, in The New York Times, she explains why in her own words. If, like I often do, you open the article in a new tab to read after you’re finished this one, don’t. Go read it. Because it starts like this:

“It wasn’t their words, it’s that I started to believe them.

Their words seemed to confirm what growing up as a woman and a person of color already taught me: that I belonged in margins and spaces, valid only as a minor character in their lives and stories.”

The fact that the essay is well-written is beside the point – but I love that it starts there. Leaves you absolutely no doubt as to what happened to Kelly Marie Tran. Confirms that people who want to make you less than, even if they’re ‘anonymous internet trolls’ as we’re all taught, have a power that can’t be outweighed by any amount of showbiz money or fame or acclaim. Tran reminds us that she is the first woman of colour to have a leading role in a Star Wars movie and the first Asian woman to appear on the cover of Vanity Fair – and still, those anonymous Twitter-egg voices are louder.

So she says she started to believe them. Was reminded that a person who looked like her could only exist in the background of stories about heroes and saviors, “doing their nails, diagnosing their illnesses, supporting their love interests”.

She’s open about the helpless frustration and anger this creates in women of colour, in anyone who doesn’t resemble a thin Caucasian ‘ideal’ – but that’s not what’s striking and new here. Nor is the part where she’s sort of writing about how these are the rules of the worlds shown in movies and TV, but really pointing out that these are the rules shown, period. It’s smart, but not new.

What’s new, to me, is that as Tran explains the lies she started believing, you get the impression that she was disappointed in herself. Disappointed that she stopped speaking Vietnamese as a kid or wondered what would happen if she were thinner. She says she felt shame for the world she grew up in, but there’s also an implicit chastising of herself, for letting those messages get in. Which makes me want to cry.

As if anyone could possibly be strong enough to resist them. As if we haven’t seen countless women, the ones we admire so much we can taste it, harassed relentlessly and viciously until they retreat. Delete their accounts, leave their apartments – until they admit to the trolls’ satisfaction that they were sorry for existing outside the lines.

Which is why, to nobody’s surprise, my favourite lines come right at the end of the piece:

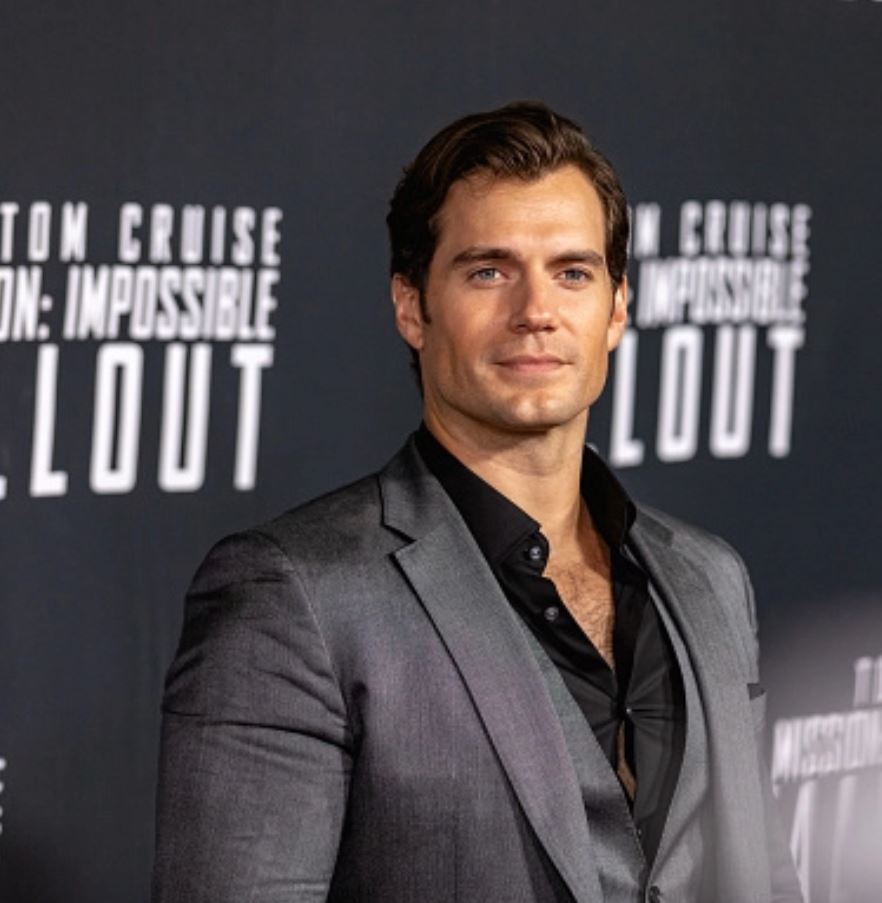

“You might know me as Kelly.

I am the first woman of color to have a leading role in a Star Wars movie.

I am the first Asian woman to appear on the cover of Vanity Fair.

My real name is Loan. And I am just getting started.”

Battle cry.

Here’s my real name that I’m not ashamed of, that I am going to wear like goddamn armor. Here’s me, exactly the way I have always been, showing you my real face and my real name and believing, for sure, that I have enough power to ignore the things I was ‘supposed’ to believe. Here’s all the things I’m not afraid to be.

Last week the incredible Elamin Abdelmahmoud wrote, in an essay about his daughter’s last name, that “names are alive and they ask things of us – sometimes too much”. I hope that Loan Tran got to read his essay. Because they share so much of the same sentiment – his essay is all about what names say, what Loan Tran’s last sentence in the New York Times tells us: that her name will remind us, every time we read or say it, that she is different. That she is not ‘fitting in’. That she is outside what’s expected or allowed.

That her name – which I hope everyone adopts the use of immediately – is the armor that gives her the strength not just to write it, but to live it.