In the Heights is (also) a college story

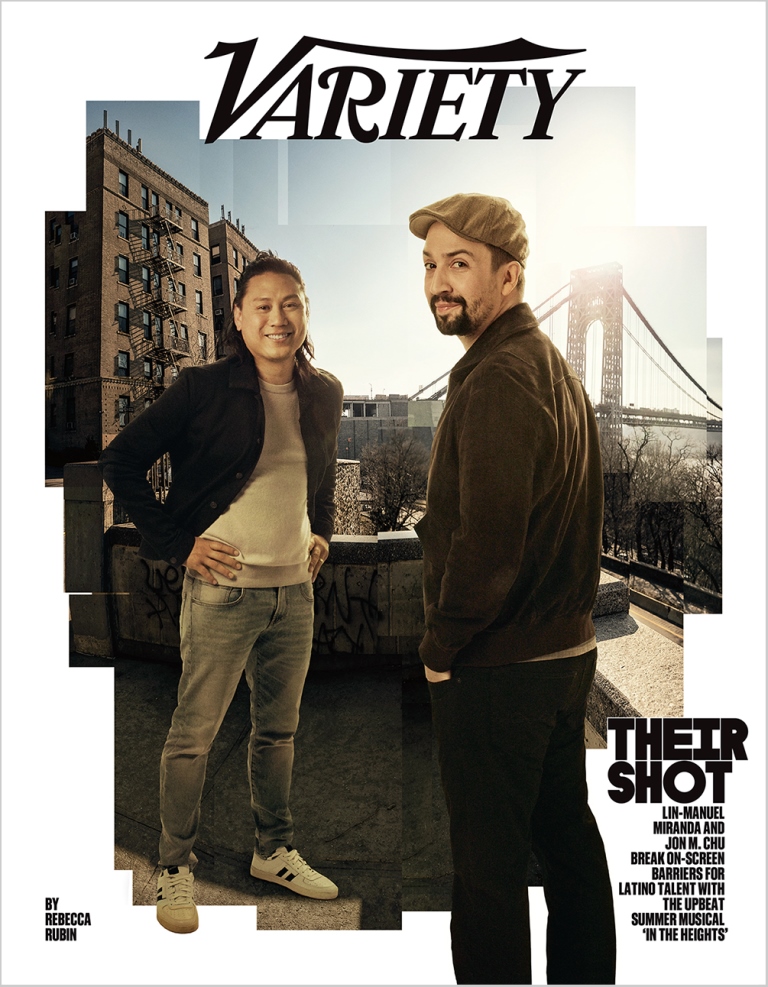

I have tried to stay away from any In the Heights content because I want to be surprised when I finally see it on my screen, but when Lainey sent me this Variety piece detailing the challenges of turning this Broadway hit into a film, I couldn’t help myself. The article had me from the hook:

“When Lin-Manuel Miranda was pitching his musical “In the Heights” nearly two decades ago, Broadway heavyweights stumbled over what he was selling. They wanted the young female protagonist Nina, who drops out of Stanford, to have a more dramatic reason for leaving school than the pressures of being the first in her family to go to college.”

“I would get pitches from producers who only had ‘West Side Story’ in their cultural memory,” Miranda recalls. “Like, ‘Why isn’t she pregnant? Why isn’t she in a gang? Why isn’t she coming out of an abusive relationship at Stanford?’ Those are all actual things I was pitched.” He pauses for a moment, not to entertain those queries but to consider their absurdity. “Because the pressure of leaving your neighborhood to go to school is f-cking enough. I promise. And if it’s not dramatic enough, that’s on us to show you the f-cking stakes.”

Many first generation college students, especially if they are students of color, experience an academic and cultural shock when they enter and navigate academic institutions. When they are the first in their family to go to college, so much of the higher education experience is new, and maybe even strange, for them. The concept of the college roommate, for example, seemed so strange to me, especially because she was literally a stranger (I had a great experience, thankfully!). I’ve mentioned before how intimidating it was to apply to college and for financial aid; my high school boyfriend helped me fill out some of that paperwork and got me comfortable with my college campus since he and his brother were already students there (yes, I followed my high school boyfriend to college. Someone option my life story for the WB! Oh wait, it’s not the year 2000). But I went to a PWI (Predominantly White Institution), so while I had “what it takes” to make it as a college student, as early as my first semester I called my mom homesick, crying, feeling out of place and lonely (my boyfriend and I had just broken up), and my mom, not understanding some of what I was experiencing in college because she had not experienced it herself, phrased a question as a declarative statement:

Why don’t you just come home.

But I didn’t come home. I “toughed” it out. And that was not the only time I wanted to quit in my higher education career. Although “wanted” is the wrong word. “Quitting” is not something I wanted. It was something that the institutions of which I’ve been a part of facilitated and even encouraged. I see this in the challenges my students face today, especially during the pandemic. Imagine starting your college career, for example, as a first generation community college student, and you’ve never stepped foot on your campus. You have a full-time job, maybe you have children, and usually you have family responsibilities that the student who “went off to college” might have been able to leave behind. It was hard for them to navigate the institution before, but now they have to navigate virtually. And many times they do not have access to the technology to do so. And so many, because they and their families are essential workers (always! not just in the past year!), have been hit by COVID hard. They have been sick, experienced loss, are struggling with their mental health and are somehow supposed to focus enough to read and write a literary analysis for my class. So much of my work this past year individually and with my colleagues has been trying to reach, support, and retain our students. But not every educator sees their job this way. And most institutions fail their students because of infuriating concepts like meritocracy and grit.

Because I’ve stayed away from reading much about In the Heights, I do not know the reasons for which Nina drops out of Stanford, but I can imagine them. The college experience can be alienating for a first generation college student, and I think “prestigious” institutions, which are predominantly white and are mostly accessible to those with privilege and wealth (check out Operation Varsity Blues and my review of it if you haven’t already), can take this alienation to another level. I can imagine that someone like Nina felt tremendous guilt leaving home and her community to pursue such an individualistic goal. I can also imagine her feeling tremendous pressure to be successful in college to do right by her community. I can see how a higher education institution, especially a place like Stanford, can push a talented and hardworking student out. I write this because I’ve seen it happen around me, because I was almost pushed out myself in graduate school, and because I’ve studied it as part of my dissertation (the irony of studying why Chicanas drop out at various levels of the education pipeline while trying to not “leak” out myself, was painful and made it even harder to write that damn thing). Imposter syndrome is real...even though it isn’t.

And this is just what the hook made me think about! There is still so much more to dissect from this piece in Variety, in particular about the circular logic of how we do not have “bankable” Latinx stars that “test international” because we never give them a chance to become stars in the first place. And they do not get that chance because there are not enough stories in movies and TV for us, even as we comprise a big chunk of that (pre-COVID) theater-going and TV-watching audience. The fact that so much of film and TV gets “made” in LA, and we cannot “make it” in LA is so damn infuriating. I always remember that Chris Rock essay in The Hollywood Reporter when he writes:

“You're telling me no Mexicans are qualified to do anything at a studio? Really? Nothing but mop up? What are the odds that that's true? The odds are, because people are people, that there's probably a Mexican David Geffen mopping up for somebody's company right now. The odds are that there's probably a Mexican who's that smart who's never going to be given a shot. And it's not about being given a shot to greenlight a movie because nobody is going to give you that — you've got to take that. The shot is that a Mexican guy or a Black guy is qualified to go and give his opinion about how loud the boings are in Dodgeball or whether it's the right sh-t sound you hear when Jeff Daniels is on the toilet in Dumb and Dumber. It's like, "We only let white people do that." This is a system where only white people can chime in on that. There would be a little naivete to sitting around and going, "Oh, no Black person has ever greenlighted a movie," but those other jobs? You're kidding me, right? They don't even require education. When you're on the lower levels, they're just about taste, nothing else. And you don't have to go to Harvard to have taste.”

But you know why I’ve written so much about just the hook of this Variety piece? Because In The Heights is a story for me! For people like me! And while I had promised myself I wouldn’t read too much more about the musical or the movie, I’ve already bookmarked screenwriter Quiara Alegría Hudes’ interview with Variety to read when I am finally done with my workweek, and I am patiently waiting for my copy of her memoir, My Broken Language, to come in the mail. I have a feeling I am about to get obsessed with everything In The Heights. There is a part of me that feels I might love it more than Hamilton. If you know and have seen both, would you agree? Will I love it so much? Or am I getting too excited?! But whether I end up loving it or not, I want so badly for this movie to do well, whatever that means in the pandemic context, because I need all of the people involved in this movie (in front of and behind the camera), to keep telling, making, and performing the stories of us who are simultaneously visible and invisible.