The Radical Empathy of Baby Reindeer

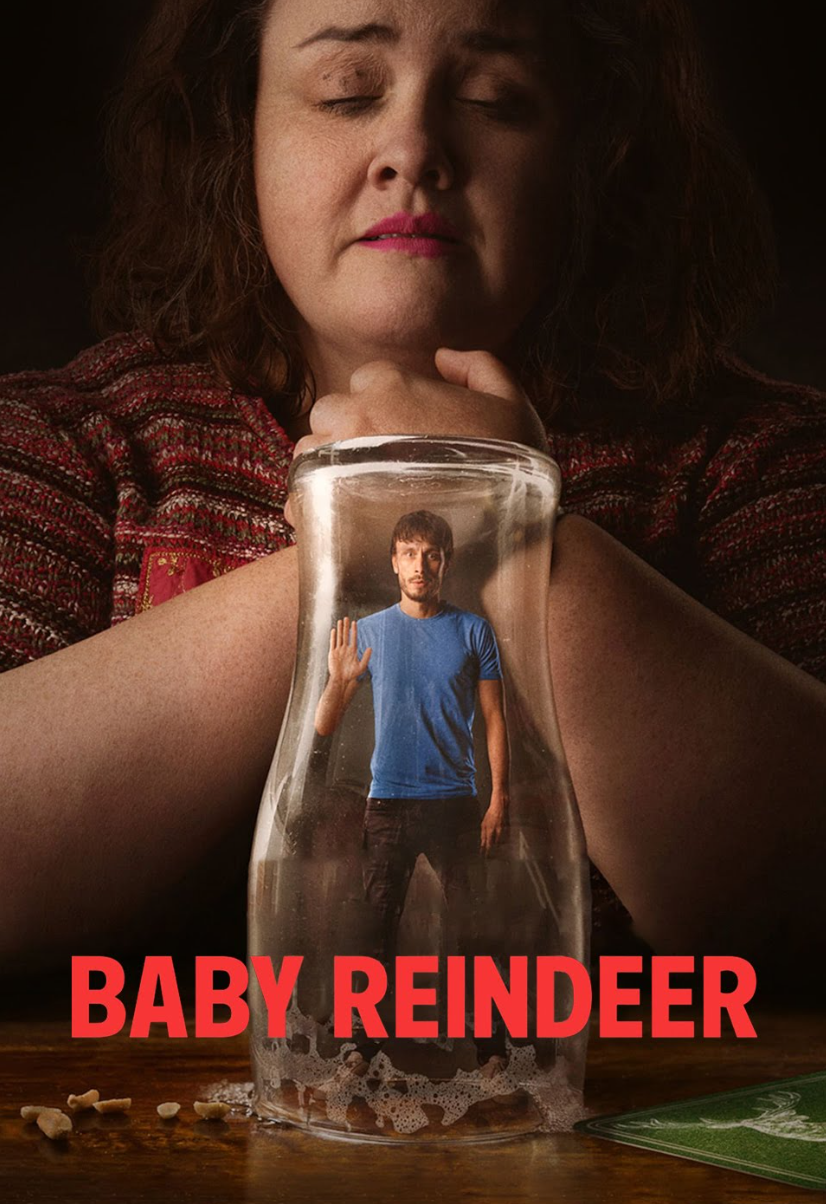

It’s been nearly two weeks since Baby Reindeer premiered on Netflix and it has understandably become a top-watched show and has dominated conversations online. The seven-part miniseries is an adaptation of Richard Gadd’s award-winning one man play. It chronicles the true story of how he, depicted as a fictionalized version of himself named Donny Dunn, a bartender and aspiring comedian, was stalked over the course of four and a half years by a woman who was given the pseudonym Martha in the series.

During his time being stalked, Richard would receive more than 41,000 text messages, 350 hours of voicemails, nearly 750 tweets, dozens of Facebook messages, 106 pages of letters and odd gifts, including sleeping pills, from her. She appeared incessantly outside his home, at his workplace, his comedy gigs and ultimately went on to harass his family members. But beyond just telling the story of his experience being a victim of a relentless stalker, the series tells the story of the events that had taken place in the years leading up to his chance encounter with Martha that, in many ways, made him even more vulnerable to her obsession.

While this series is a sharp departure from my reality-filled, trashy TV consumption, I found myself so enthralled and so moved by Richard's myriad experiences, which he bravely put on display for us all to see, speaking to the innate human desire to feel seen, to feel love and acceptance and mostly, to make sense of the things that transpire in our lives.

So what is it that makes this story so remarkable? Why is it currently the number one watched show in Canada on Netflix? Judging from the conversations online, a lot of the show’s success has to do with the fact that it’s a much-needed reminder that when it comes to stalking and sexual assault, men can be victims, too. But I think that goes without saying. And I’d hope that with documentaries like Scouts Honour and movies like Procession and Spotlight, that it’s something we remember without necessarily having to be prompted.

For me, though, Richard’s series was such a gripping watch because of the way it explored the nuances of assault, shame, vulnerability and empathy – things that, when intertwined, were shown to have had a profound impact on Richard’s life and his sense of self. And it’s done in a way that only a few series before it, namely I May Destroy You and perhaps Fleabag, have been able to – managing to strike a near perfect balance of a rather dark and painful story that just so happens to still be comedic.

Richard’s chance encounter with Martha begins when he offers her a cup of tea on the house once she stated that despite being a lawyer, she couldn’t afford it. While their initial interaction was friendly and not anything unlike you might witness between a bartender and a patron, it spirals into an unrelenting obsession that leaves him with very little room to breathe or find solace – not in his friends, his series of romantic partners, or his local police department.

As the stalking intensifies, Richard finds himself developing a very complicated, and at one point, even a sexual relationship with Martha, for whom his empathy leads the viewer to question, at times, particularly in the beginning of his stalking ordeal, who the true victim is, and perhaps what a true victim might look like, and even what a stalker might look like.

“Stalking on television tends to be very sexed-up. It has a mystique. It’s somebody in a dark alley way. It’s somebody who’s really sexy, who’s very normal, but then they go strange bit by bit,” Richard told Tudum, by Netflix. “I think art is quite interesting when you don’t know who you are on the side of. I wanted it to be layered, and I wanted it to capture the human experience. The human experience is that people are good, but they have bits of bad and they make mistakes.”

The idea of the human experience and the complexities of it was something he explored further throughout the series, particularly in his response not only to being stalked, but to being sexually assaulted by an older man who was a successful TV writer. What was first an invitation for mentorship became a heartbreaking series of instances where Richard found himself being groomed by this man, who encouraged him to use hard drugs with him, though later he would question whether he was the only one getting high. The come-down from these trips often included some form of sexual abuse, and the fourth episode depicted Richard being sexually assaulted.

Following the assault, during a narration, he describes feeling like he wished he had left the man’s house promptly after. But he ended up staying there, not leaving until several days later. Perhaps many would view this as atypical behaviour for an assault victim, but again, Richard wanted to show that abuse is not linear, and neither is the response to it. This is something he spoke to not only in the series, but also in real life, saying:

“I don’t want to speak for every person that’s been sexually abused, but one of the most common ramifications is self-blame,” he said in an interview with The Independent. “‘Why did I go there? Why did I do this?’ Why did I… blah, blah blah. I’ve lived in a prison of self-hate and self-punishment. But writing it down in a chronological way, and processing it… I guess I learned to empathise with myself a little bit more.”

This is what makes the series so unique and so hard to look away from. The audience was given an invitation to have an intimate look at Richard rediscovering empathy for himself as he navigated impossibly painful, but sadly not entirely uncommon experiences. Common enough that upon opening up to his parents about being sexually assaulted, with fears they might view him as “less of a man”, that his own father reveals he was abused, too, while growing up in the Catholic church.

The idea of masculinity and what it means is such a passive but still prevalent question being posed at every turn in the series, particularly as we see him struggle to define his sexual identity and the impact his assault may or may not have had on it. His male friends are constantly laughing off his “admirer”, refusing to acknowledge the danger she continues to put him in. His friends and colleagues fail to enforce her being banned from the bar he worked at which led to him being physically assaulted with broken glass by a vengeful, rageful Martha. They pull up his comedy skits and laugh, for all the wrong reasons, at Richard. And when he brought his concerns to the police, they, in a not so shocking turn of events, inform him that “there’s nothing they can do”, leading him to have to become his own advocate, consumed with proving the severity of his case, playing her voicemails “like a podcast” until he was able to catch her finally uttering threats.

Besides all of that, the audience gets to see the impact his assault had on his ability to be intimate, or rather, to accept intimacy from the people he had been romantically, or at least sexually, involved with which culminates in a polarizing series of meaningless hookups and heartbreaking breakups. The depth of his reasoning behind not being able to be intimate went so far beyond the typical assumption that one simply “can’t get it up”.

Finally, during a comedy set with a tough crowd, he breaks down and reveals the state of his life. He shares that he’s being stalked. He shares that he had been assaulted. And when the video of his breakdown goes viral, his parents, prompted by his in-person visit rather than the viewing of the video, were the first ones to truly return an ounce of the empathy we’d seen him give to his stalker. And after spending some time with them, receiving both love and validation, his comedy career takes a turn for the better and inklings of him healing begin to show.

Even after that, though, he revisits his rapist. And he commits to doing more work with him. His decision is, again, something that might raise an eyebrow. But any audience member who has taken heed to arguably the biggest point of the whole series knows not to judge, but to understand, and to extend empathy. Because for Richard, it’s part of his healing process. And it’s part of his human experience.