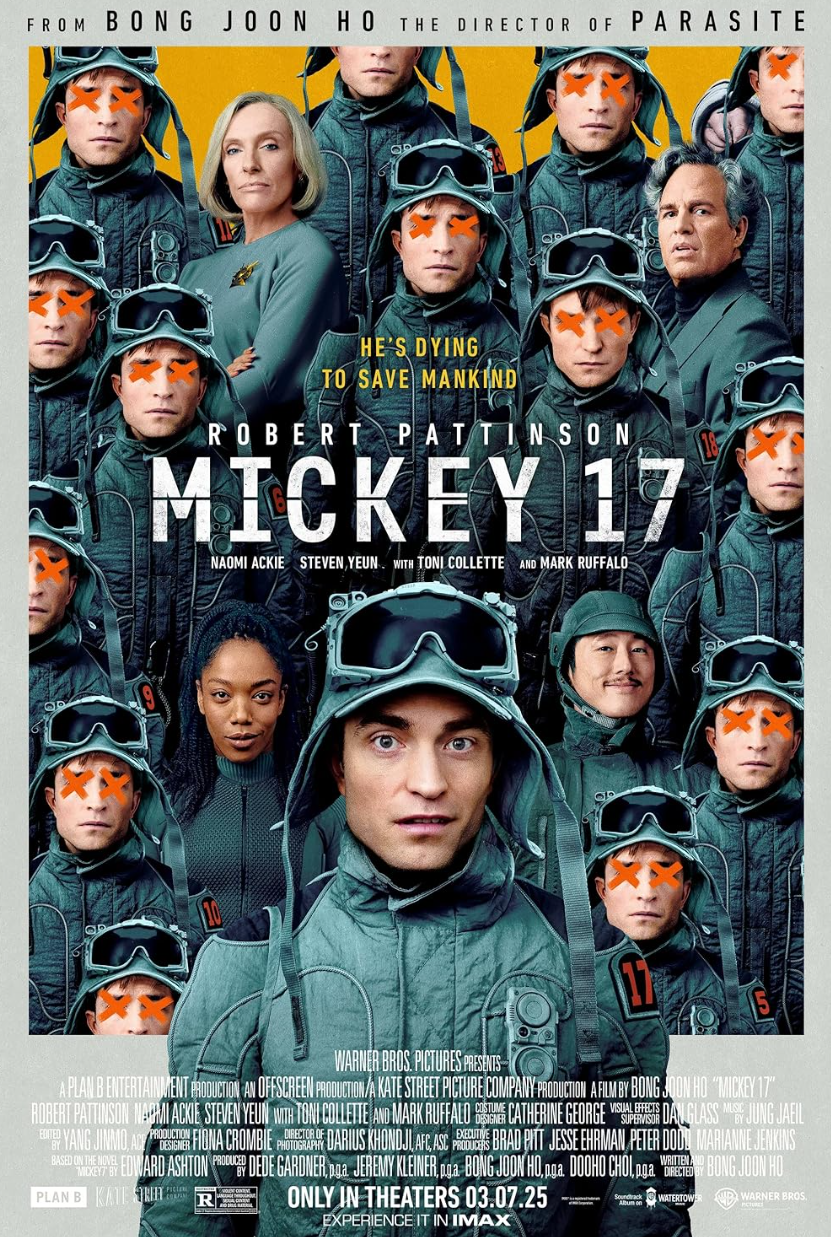

Robert Pattinson (and Robert Pattinson) in Mickey 17

Six years after winning multiple Oscars for Parasite, South Korean filmmaker Bong Joon-ho is back with Mickey 17, a return to science fiction for Bong, though with a dash of Parasite’s class-consciousness. Written and directed by Bong (adapting from Edward Ashton’s novel, Mickey7), Mickey 17 is set in the near future of 2054, when humans are exploring space and colonizing and mining alien planets for resources. Robert Pattinson stars as Mickey Barnes, whose macaron shop failed on Earth, forcing him and his best friend, Timo (Steven Yeun), to flee Earth and a vicious loan shark.

If that sounds a little comedic, it is. Mickey 17 is doing a lot and most of it well, and one of the things it does best is comedy. This is a funny movie, rife with jokes, comedic performances, and stellar visual humor (Pattinson’s physical comedy is wonderful). But for all that, the premise is still pretty dark—once on the snow planet Niflheim, Mickey, who did not read the fine print on his employment contract, is subjected to agonizing death after agonizing death, with his memories copied and downloaded into newly printed bodies every time. He is an “expendable”, a permanent sacrifice made in the name of progress—his deaths help doctors devise a vaccine that renders Niflheim habitable to humans.

But it is already a habited planet, full of creatures called “creepers”, which kind of look like roly-poly bugs. This leads to a conflict between the humans and the creepers, with the humans, led by sequined authoritarian nightmare Kenneth Marshall (Mark Ruffalo, giving a performance that probably felt inventive and vaudevillian when he gave it in 2022, but now reads as a Trump riff), treating the creepers like a nuisance to be eradicated. Mickey 17 is not subtle, the colonization and exploitation allegories are barely even that, the subtext is just the text.

Mickey 17 feels like a culmination of ideas Bong previously explored in Snowpiercer, Okja, and Parasite, which might make it feel like a retread, depending on your patience for artists working out their thoughts in real time through their work. “Retread” is one way of looking at it, a more generous read is that Mickey 17 is the latest iteration in Bong’s continually evolving ideas about colonization, capitalism, environmentalism, exploitation, and slapstick humor. For instance, the class metaphor is less tortured here than it is in Snowpiercer, with the literal compartmentalization of a train representing socio-economic brackets. There is also no “I know what babies taste like” monologue, for which we are all grateful. Similarly, Ruffalo’s performance feels like an evolution from Jake Gyllenhaal’s over-the-top turn as a TV personality in Okja.

There are a lot of common elements between these films, but that is because they are in conversation with one another. Bong clearly has some thoughts he is still parsing, but your patience for that might be different than mine. For my part, I was delighted to spend a couple hours (and change) with Bong and another immaculately rendered sci-fi world, never mind the A-list cast giving a slew of incredible performances, led by Robert Pattinson. He is obviously having the time of his life, playing Mickey 17 and Mickey 18, co-existing “multiples” fighting for their survival. Mickey 17 is goofy and kind of obnoxious, Mickey 18 is driven and take-charge. Their shared girlfriend, Nasha (Naomi Ackie), dubs them “mild Mickey” and “habanero Mickey”.

Their coexistence is forbidden, but they each feel entitled to live, and the question of who the “real” Mickey is moot when they’re both late-generation knockoffs of the original, with the same set of shared memories. Personality-wise, though, they are clearly different people, neither of whom will be satisfied by the half-life secret survival demands. Again, the allegory is not subtle relating to the themes of capitalism—bodies are resources to be extracted, individuals are dispensable—but Bong is playing with identity in an interesting way. It’s not just the Mickeys, he also explores identity through the creepers, who turn out to be sentient, if alien, with a strong sense of community and justice.

For all that his work can be bonkers, Bong is a deeply humanist filmmaker, who places a premium on life. And it’s not just human life that matters, as with Okja, Bong posits that how we treat life other than our own says a lot about us as people and as a society. The creepers plot almost feels like a counterpoint to Starship Troopers. Mickey 17 definitely shares a satirical edge with that film, but where filmmaker Paul Verhoeven and screenwriter Edward Neumeier (adapting from Robert A. Heinlein’s novel) lean hard into cynicism, Bong leans into humanism. Mickey 17 isn’t entirely optimistic, Bong is too clear-eyed about the failings of humanity for that, but he is also not giving up on the notion that we are capable of doing and being better. Like all of Bong’s work, Mickey 17 includes a ray of hope.

The film’s edges don’t all completely line up—it feels like at least 20 minutes was cut out of the film—but though it’s a little messy, it works more than it doesn’t. And it’s anchored by Robert Pattinson’s frankly brilliant dual performance. It would be worth watching just to see Pattinson do his thing twice over, but there is also the pleasure of watching a thoughtful filmmaker continue evolving the thesis driving his work from one film to the next. Bong Joon-ho’s work is big in scope and ambitious in scale, but he never loses sight of the people—or creatures—at the heart of his stories. Mickey 17 is the latest in his ongoing exploration of humans’ capacity for compassion in the face of cruelty and strife. It’s a hilarious, gross, cuttingly satirical tribute to the human spirit.

Mickey 17 is now playing exclusively in theaters.