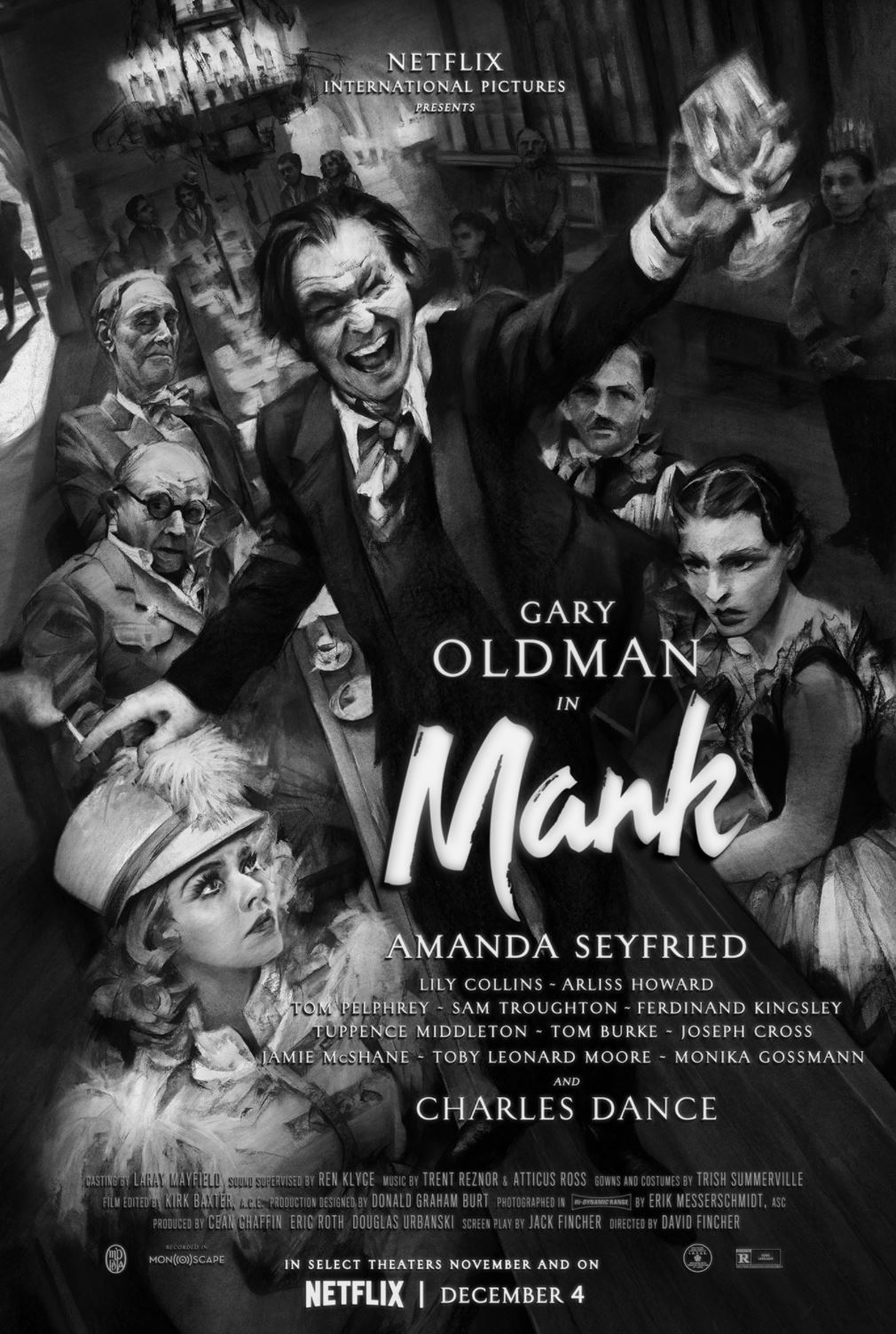

Gary Oldman and Amanda Seyfried in Mank

David Fincher is too technically proficient as a director to make a really bad movie. Even his less interesting efforts will have something worth looking at, and Mank is certainly one such case. A biopic of screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz, Mank is an odd Fincher misfire. It’s based on a screenplay written by his late father, Jack Fincher, and it feels like a dutiful son realizing his father’s dream project, while his own dream project is actually a biopic of Upton Sinclair. Mank is disheveled in ways Fincher films usually are not, as if he was unwilling to disturb his father’s script even to make it better, and it features a couple of baffling decisions that are more distracting, less artful. Mank does, however, feature Amanda Seyfried saying, “Aw, nerts,” with total sincerity, and for that, she should win a special award.

One of the baffling decisions of Mank is its look. Fincher, a filmmaker with a reputation for painstaking staging, meticulously recreates the look of a 1940s Old Hollywood film, right down to cigarette burns on the film print. Only problem: there is no film print. Fincher shot this film—lensed by Mindhunter cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt—utilizing digital equipment and adds the pops and imperfections of aged celluloid with computers. The result is a satiny black-and-white film with conspicuous “flaws” completely at odds with the smooth, polished look of digital. Why not just shoot on film and work in some of these blemishes manually? It’s not that Mank is bad to look at, it isn’t. It is a very handsome film. There’s just an inherent conflict between the polish of digital and the imperfections of celluloid that does not reconcile and adding celluloid-style imperfections to a digital film doesn’t make the digital look more “authentic”, it just highlights the CG imperfections.

Strange camera decisions aside, Mank is a reasonably effective biopic of Mankiewicz. It hop-scotches through the 1930s, providing context for how Mank ended up writing Citizen Kane (who wrote what in Kane is one of cinema’s most enduring and least interesting debates). Recruited by a young Orson Welles (Tom Burke), Mank is sent to a ranch in Victorville, California to work on the script while recovering from a serious car accident. He also needs to dry out, as Mank is, by the time, well and truly sunk into his alcohol addiction. This leads to odd choice number two: Gary Oldman, aged 62, plays Mankiewicz whose peak age only hits 43 in this film. His performance is boozy and verbose and bitter and is completely fine except for the way that he never not once looks like a washed-up 40-something. The film cheekily nods at the discrepancy, but it runs into the same territory as The Irishman—at a certain point, there is movement that speaks of age and nothing overcomes it. When Mank is bed-ridden and delivering soliloquies from a prone position, it’s fine, but the moment Oldman is up and moving any reference to Mank’s age becomes distracting.

There are other oddly overlooked mistakes—like a flashback to 1930 of Mank and his writer pals pitching a film to counter the monster movies at Universal…which have not even been released…but Mank largely cruises on Oldman’s performance and a great turn from Amanda Seyfried as Marion Davies, the long-time mistress of William Randolph Hearst (played in the film by an overly regal Charles Dance). Seyfried blends her natural charm with the weariness of a woman who has subsumed her own ambitions to satisfy those of her powerful lover. Davies is widely regarded as a gifted comedienne and Hearst’s interference in her career did more harm than good, and Seyfried manages to convey all that while also communicating her staunch loyalty to him. She is genuinely great here, where Oldman is miscast, Seyfried is perfectly suited to her role.

The making of Citizen Kane probably won’t interest anyone outside film buffs, but Mank also offers a look at how early Hollywood utilized its fantasy machine to influence popular opinions and political machinations. Mank’s whole deal is that he thinks he’s too good for Hollywood, which he sees as a cash grab and not a real artform, like theater, or important, like journalism. Therefore, he misses the power and impact cinema can have, which means he is blindsided when Louis B. Mayer (Arliss Howard) and Irving Thalberg (Ferdinand Kingsley) create fake news reels to stir anti-socialist sentiment during the 1934 California governor’s race in which Upton Sinclair is running (look for a fun cameo from Bill Nye as Sinclair). The Hollywood machine breaking the back of a progressive political movement feels like what Fincher really wants to be talking about in Mank, but he gets stuck with all this other stuff about Hearst and Kane, too.

This is not top-tier Fincher, though there are worthwhile elements in Mank, like Amanda Seyfried’s performance. Mostly I wish Fincher took his subject a little less seriously – an example would be the Coen brothers’ approach to 1950s Hollywood in Hail, Caesar!. That is a film imbued with sincere love of subject, but it’s handled with a light, affectionately cynical touch. Mank feels like a perfectionist going through the motions—all technical achievement and no heart. It’s like a meticulous diorama of a subject no one was asking about, presented for no reason anyone can grasp. Fincher fans or extremely devoted Citizen Kane nerds who must consume any and all media about Kane will likely be amused, but everyone else will be left cold by Mank.

Mank is now streaming on Netflix.