Theo James in The Monkey

Osgood Perkins has been making high-quality horror since 2015’s The Blackcoat’s Daughter—he comes by it honestly, he’s the son of Psycho star Anthony Perkins—and broke out in the mainstream with last year’s serial killer sleeper hit, Longlegs. Now, he’s back with The Monkey, an adaptation of a Stephen King short story about a fateful figurine and the beleaguered owners who run afoul of its demented purpose. Forget the structural elegance and moody atmosphere of Perkins’ previous work, in The Monkey he throws good taste out the window in favor of a Looney Tunes-level of violence and gore.

The film has a blazingly good cold open set in 1999 and featuring Adam Scott as a frantic, blood bespeckled pilot trying to offload a vintage drumming monkey figurine—do NOT call it a toy. The pilot, Petey Shelburn, fails to get rid of the monkey and then disappears, leaving behind a wife, Lois (Tatiana Maslany), and twin sons, Hal and Bill (played as children by Christian Convery). Hal is the sweet one and Bill is the budding psychopath who probably tried to eat his twin in the womb and failed. They discover the monkey amongst their father’s effects and quickly learn The Monkey’s Rules.

Everyone knows all old-timey toys are haunted, and the monkey has some kind of spiritual hotline to death. Turn the key in its back, and it will bang its drum, and someone will die. It can’t be directed, though, the deaths are as random as they are gruesome. The Monkey seems as much influenced by Final Destination as Stephen King, and Perkins directs the death scenes with the vigor of someone who definitely went through a Carrie phase in high school. You can practically hear the gleeful guffaws echoing from set as gallons of fake blood spray across the screen. If you’re not into gore, The Monkey is not for you. But if you love Final Destination for its unrelenting creativity, or if you shudder but grin at every particularly wet kill in a slasher movie, come on in, sicko, this one’s for you.

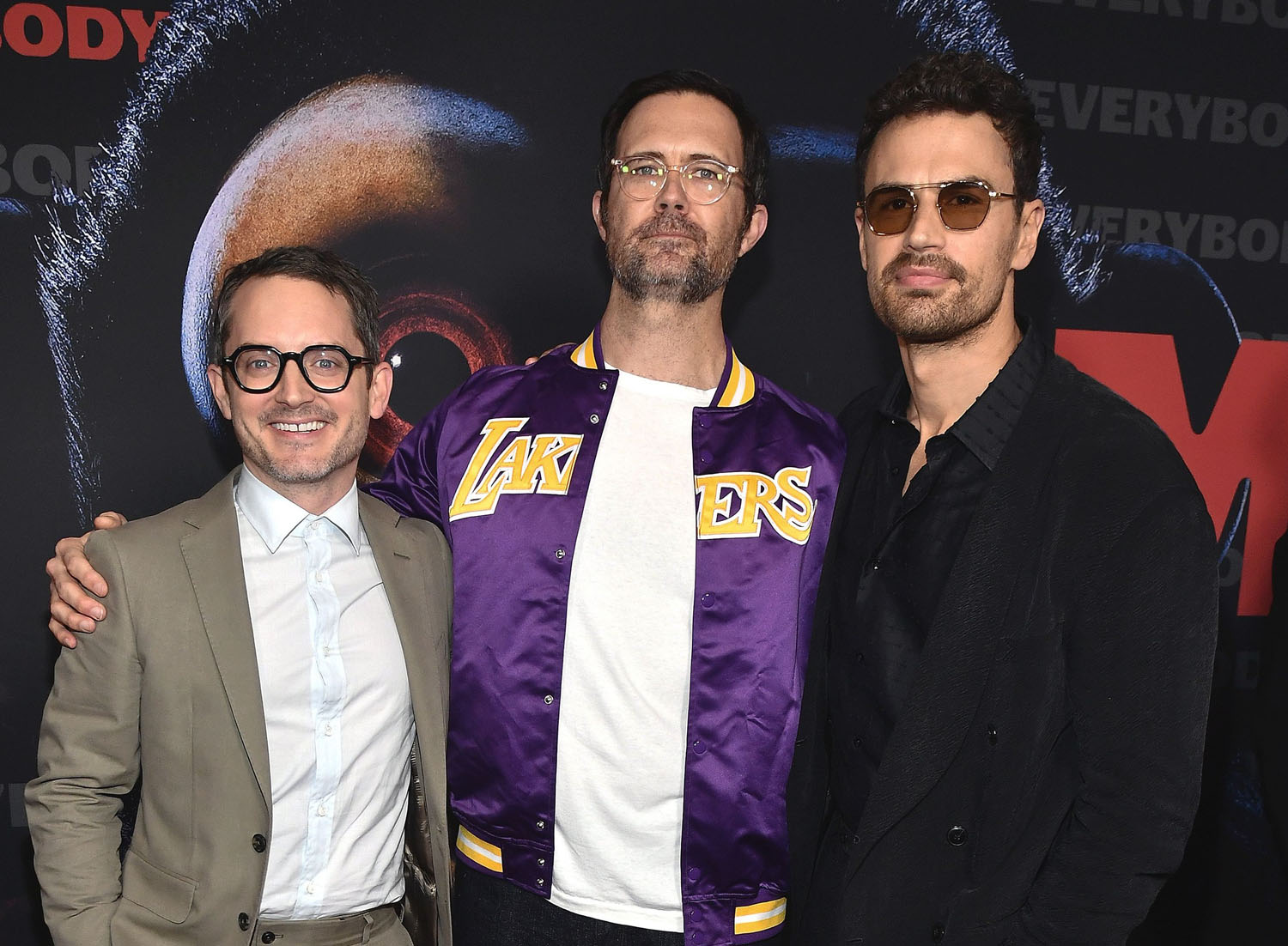

In short order, the monkey costs young Bill and Hal enough that they attempt to get rid of it, dropping it down a well. That works for twenty-five years, and then the deaths start up again. Hal and Bill are now grown and are played by Theo James in a dual role, helpfully wearing glasses to distinguish between the twins. They have become estranged, and Hal is also a parent who is also estranged from his son, named Petey (Colin O’Brien, providing a sound emotional core to the film) after his father. Afraid of the monkey and its incalculable death radius, Hal stays away from his son, who is about to be adopted by his aggressively therapizing stepfather, Ted (Elijah Wood). Fearing the loss of his son, Hal risks the monkey’s wrath to spend time with Petey.

What follows is a blood-soaked romp through family bonding and reconciliation. The monkey is awake and drumming, people are dropping like flies, Bill has a grudge, Hal is just trying to spare his sweet son the monkey’s madness. Perkins obviously decided to go full bonkers with the death scenes, but there is a version of this film that is more aligned with his previous work, something darker and quieter and more deeply invested in the family dynamics at play. As is, the theme of filial estrangement and reconciliation is a sturdy framework for Perkins’ deranged little murder scenes. It definitely adds to the film, but The Monkey isn’t really about emotions. It’s about the deaths. So, so many deaths.

The Monkey feels like a throwback to Tales from the Crypt, Final Destination, and splatter-fests like Chopping Mall and Killer Workout. Osgood Perkins has too good an eye for The Monkey to look anything less than gorgeous (aided by cinematographer Nico Aguilar), but it’s got the same kind of unrepentantly gory sensibility of Eighties slashers and the teen horror-comedies they inspired. The Monkey is reclaiming horror from “elevated” status and giving it back to the sickos who live for body counts and blood splatter.

The Monkey is now playing exclusively in theaters.