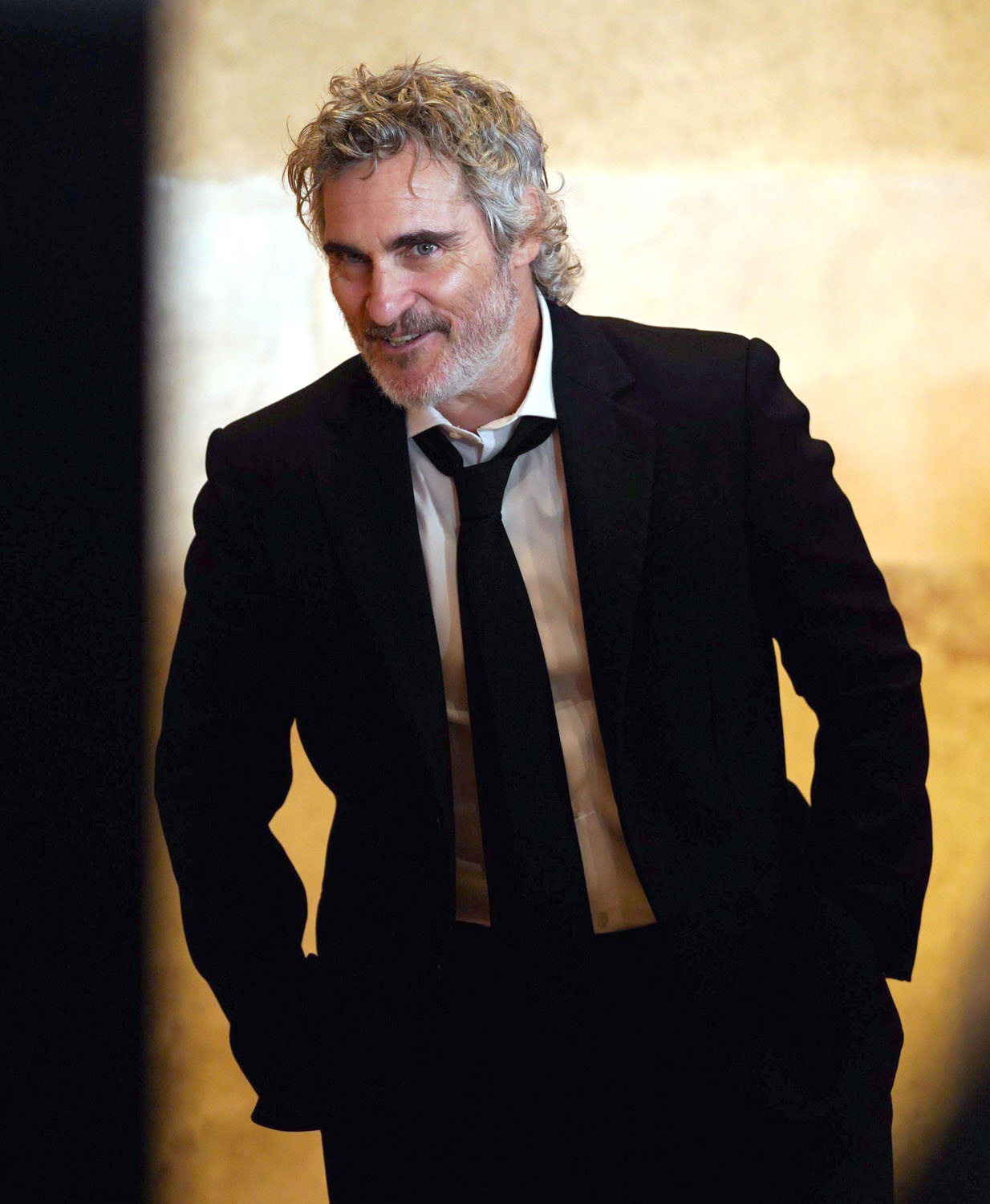

Joaquin Phoenix and Vanessa Kirby in Napoleon

Two popular images of Napoleon Bonaparte survive 200 years after his death: 1) Napoleon the bold military strategist who nonetheless ran into the insurmountable wall of a Russian winter, and 2) Napoleon the weird little guy who was led around by his dick by his older, promiscuous wife. Smash these impressions together and you get Ridley Scott’s Napoleon, a battle epic that is less interested in historical accuracy and more interested in how rumors and gossip shape that history, and how those exaggerations survive and morph into our popular impression of historical events and figures. If you’re an un-fun nerd who insists on total historical fealty, Napoleon is not the film for you, but for everyone else, it’s a wildly entertaining and surprisingly funny film about one weirdo who had an outsized impact on European history.

Napoleon Bonaparte (Joaquin Phoenix) happens to witness Marie Antoinette’s execution at the height of the “Reign of Terror” during the French Revolution. This almost certainly didn’t happen, but who cares? The point is the juxtaposition of Marie Antoinette, proudly defiant, marching to her doom as Napoleon slinks around the edges of the crowd, a misfit in the right time and place to seize power. He is then a lowly officer being presented to revolutionary leaders to take command at Toulon, a port city under siege by combined Anglo-Spanish forces. The French are outgunned, outmanned, and outshipped, but Napoleon has a plan to tip the balance of power by seizing one fort.

In classic Ridley Scott fashion, the siege is depicted complete with graphic horse murder. It really feels like Scott was just waiting for the technology to get to the place where he could stage anatomically correct horse murder, which is horrible, as is a later scene when Napoleon orders cannons fired on citizens protesting in the streets of Paris. As graphic as the result of a cannonball blasting through horses and humans is, it illustrates one of the central tenets of the film—Napoleon Bonaparte built his life, his empire, and his legacy on immense, almost unimaginable pain and suffering. The film makes a stark point of how steep the price of Napoleon’s vanity was.

But that’s just one part of the film. The rest of Napoleon is concerned with Napoleon’s life behind closed doors, particularly his relationship with his first wife, Josephine de Beauharnais (Vanessa Kirby). A survivor of the Reign of Terror—though her first husband was not—Josephine is a few years older and a lot more elegant, sophisticated, and hollowed out by what she has experienced. Napoleon is immediately smitten with her, but she only latches onto him once she understands the power and protection that he can offer her and her children. While she is not repelled by him, she’s also not particularly into him, except as a buffer between her and the cruelty of the world. Yet she marries him.

Napoleon is a horndog who demands sex by smacking his lips like a baby rooting for milk, and who calls sex “cockwork”, which I can never forget and now neither can you. Josephine tolerates his unskilled humping and makes up it for later with a handsomer, younger lover, Hippolyte Charles (Jannis Niewöhner). But rumors of Josephine’s indiscretions reach Napoleon in Egypt, and he quickly packs it in to return home to Paris to demand that Josephine love him. It is extreme loser sh-t, because Napoleon is an extreme loser. He’s awkward and uncouth and disinterested in anything that isn’t Josephine, martial victory, and getting an heir. His love for his wife comes across as possessive, not affectionate, and his obsession with having an heir is an obvious red flag for the future.

Where Napoleon excels is in Phoenix’s portrayal as Napoleon as a man singularly lacking in self-awareness, yet who has the savvy to invent his own legend on the go (the depiction of his victory at the Battle of Austerlitz is based on the heavily propagandized story Napoleon himself put forward). Napoleon is such a loser his own dog can’t stand him, even as he notches victories on the battlefield, he remains a pillock who repels people and animals alike without even trying. Even a mummy dead thousands of years does its best to get away from him in one of the film’s best visual gags.

Where Napoleon falls short, though, is primarily around Josephine herself. Vanessa Kirby is excellent as Josephine, crafty and sexy and scared, but she is shortchanged by the script and the editing (by Claire Simpson and Sam Restivo). The film runs two hours and thirty-five minutes, but there is allegedly a four-hour director’s cut coming. Maybe the theatrical cut should work in and of itself, though, even if it means going for a longer film. Because Napoleon has a lot of ideas but not a lot of focus, and Josephine suffers the most for it, which is unfortunate because the best parts of the film aren’t the battles, it’s Josephine and Napoleon in their unholy matrimony, shaping the world around Napoleon’s ego and dick.

The film picks back up, though, in the final half hour when the Duke of Wellington (Rupert Everett) arrives for the Battle of Waterloo. Napoleon is certainly a gifted military strategist, but the moment Wellington arrives, Napoleon becomes an entirely different film. Napoleon’s shortcomings are thrown into sharp relief when contrasted with another gifted military strategist, and one who has a modicum more humanity than Napoleon. Wellington is no peach, he’s a wretched snob, but he, at least, shows some emotion when faced with the human toll of Waterloo. Napoleon is totally unmoved by the death and suffering of his men, he cheers them as “heroes of Austerlitz” yet does not hesitate to throw them in front of cavalry and cannons, refusing to admit defeat even though he is outmatched as of the first day of battle.

What unites the disparate strains of the film as it exists right now—who knows what’ll go on with that four-hour cut—is how rumor and gossip weave around Napoleon and Josephine and dictate so much of their lives, and in turn, everyone else’s. So many of Napoleon’s impulses are determined by rumors about Josephine, so many of Josephine’s actions are guided by splitting the difference between keeping herself safe and reflecting well on Napoleon. Even their famed love letters, used as inner monologue voice overs, serve as merely one more facet of gossip, and Napoleon is keenly aware of how his letters will be—and were—used against him to skew his popular image.

Napoleon is the confluence of two centuries of documentation and innuendo, the tension between what is and what is believed to be, and how, maybe, a tyrant who led millions to their death doesn’t deserve better than to be portrayed as a weird little guy horny for his mean wife.

Napoleon is now playing exclusively in theaters.