Shyamalan’s homegrown superheroes: Revisiting Unbreakable

(Ahead of the release of Glass this Friday, we are running a miniseries of posts on the Unbreakable trilogy, or the Eastrail Trilogy, by M Night Shyamalan. This is the first, on Unbreakable. Tomorrow we will follow with Split.)

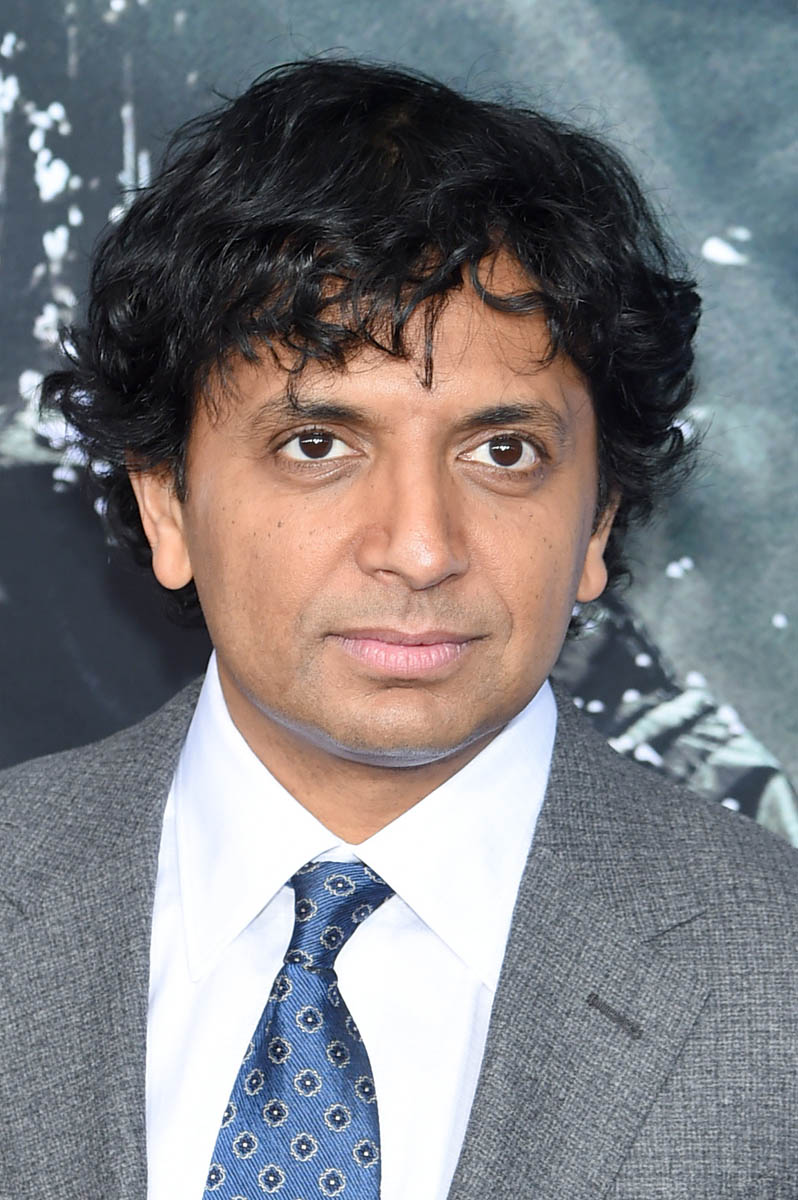

It’s easy to forget, because he’s become a pop culture punchline, that when he first emerged, M. Night Shyamalan was widely regarded as the next Alfred Hitchcock. The Sixth Sense launched him into the stratosphere in 1999, garnering massive box office, critical praise, and earning Shyamalan two Oscar nominations (for writing and directing). So the hype and pressure on his follow-up, 2000’s Unbreakable, was unbearable, and indeed, Unbreakable could not hold up under the weight of expectations. It wasn’t an outright flop, but its $95 million domestic run was almost $200 million dollars under The Sixth Sense, and though critics generally liked it, everyone admitted the ending wasn’t as good as The Sixth Sense. In hindsight, Unbreakable never really stood a chance, between the worldwide success of The Sixth Sense and its own quieter, less “gotcha” approach to storytelling it was destined to be The Sixth Sense’s misfit younger brother.

But time has been kind to Unbreakable. In 2011, Time ranked it #4 on its list of Top Ten Superhero Movies of All Time, and though audiences hated it back in 2000 (giving it a C CinemaScore, indicating overall dislike), it has become a cult classic. And Unbreakable deserves that status, because it is still Shyamalan’s best-made movie. Think whatever you want of his twist-centric storytelling, Shyamalan is one of the best filmmakers around when it comes to mis-en-scene, his staging and photography carefully considered and constructed, with every placement and movement designed to complement the story. The Sixth Sense staged every scene to hint at the film’s big reveal, but Unbreakable is not really about a big reveal—which is a large part of why audiences didn’t like it, it turned out not to be a puzzle—and its staging is more about creating a live-action comic than any surprise ending.

Of course, there is a surprise, because it’s M. Night Shyamalan—and here, I guess, are spoilers for a movie that is nearly twenty years old—but in Unbreakable the twist isn’t a twist so much as a reveal that has been building all movie. It’s not really shocking when Elijah Price (Samuel L. Jackson) turns out to be a self-appointed villain called “Mr. Glass”. He’s been talking about heroes and villains the whole movie and has made no secret of the fact that he believes in real-life superheroes. It figures there would be a villain somewhere on the stage, and besides the family of potential superhero David Dunn (Bruce Willis, in one of his last actual performances), there are no other significant characters in Unbreakable. Price HAS to be the villain, by default. Unbreakable is not a puzzle and Shyamalan isn’t really hiding anything except the one secret Price would, naturally, keep from Dunn.

What has made Unbreakable one of the best superhero movies is its brilliantly simple premise, “What if Superman didn’t know he was Superman”, and also Shyamalan’s carefully crafted comic book world. This is not a world of alien invasions and laser guns. There is no talking raccoon or superhero supergroup. But more than any other superhero movie, Shyamalan crafted Unbreakable to LOOK like a comic. It has a simple, bold color palette: green and purple. Many scenes are shot with the kind of chiaroscuro comic book artists use in dramatic cells. The character silhouettes are sharp and clear: David defined by his hooded poncho and Elijah by his stand-up hair and tailored clothes, particularly those sharp lapels. Many scenes in Unbreakable have quadrilateral framing, creating cells within the frame to echo a comic book page. No live-action superhero movie has looked as much like a superhero comic as Unbreakable.

But it’s not that Unbreakable is a pretty movie—it isn’t. If anything, it recalls the ugly-on-purpose aesthetics popular in the 1980s. It is, however, essentially a comic book come to life, right down to the simple morals spouted by its characters. Shyamalan’s view on comic books and superheroes is not particularly sophisticated even by 2000 standards (aka, the time before people started taking comics and superheroes seriously), but the way he grounds his thesis in a classic strong-man premise forms a strong backbone for the film. Unbreakable holds up the best of any Shyamalan film because it never tries to be bigger or more complex than its core idea of “if hero, then villain”. It creates a world of superheroes and teases a bigger story to come, only audiences didn’t like it and it didn’t make quite enough money, so Unbreakable was stranded, an origin story with no main. Until, that is, Split.