TIFF Review: Pamela Anderson is The Last Showgirl

The Coppola filmmaking dynasty is full of notable directors, writers, and actors, and with The Last Showgirl, director Gia Coppola announces herself as the latest Francis-spawn (he’s her grandfather) that must be taken seriously.

Nine years after her feature directorial debut, Palo Alto, Coppola delivers a film that feels entirely and uniquely hers, even as she shares it with Pamela Anderson, who gives a career-defining performance as a Vegas showgirl being unceremoniously shoved out of her industry. The Last Showgirl is also a calling card for screenwriter Kate Gersten, who leaps from television comedies like The Good Place and Schmigadoon! into a considerably darker, bleaker world. These women come together to tell a story about ageism, sexism, and dreams in a city built on ass and artifice, and the result is a haunting film centered on one of the best performances of the year.

Le Razzle Dazzle is the cheesy name of the last topless showgirl revue on the Las Vegas strip, a holdover from a previous era, when showgirls reigned supreme in Vegas. The show’s longest-serving dancer is Shelley, played by Pamela Anderson with a wispy baby voice that at times sounds like Marilyn Monroe, and in other moments just sounds exhausted. To say that Anderson is a revelation is almost unfair, as she simply never had a chance at any point in her career to deliver a performance like this. But she is astounding as Shelley, in turns innocent, vulnerable, manipulative, mean, selfish, and selfless. Shelley is an anachronism, earnestly proud of her job even though everyone else sees it as tacky and exploitative, she still uses landlines and Walkman tape players, her house is decorated with a mix of 80s home goods and Vegas kitsch. Shelley is very much stuck in the past, clinging to a glamour that has long since faded from showgirls and Las Vegas.

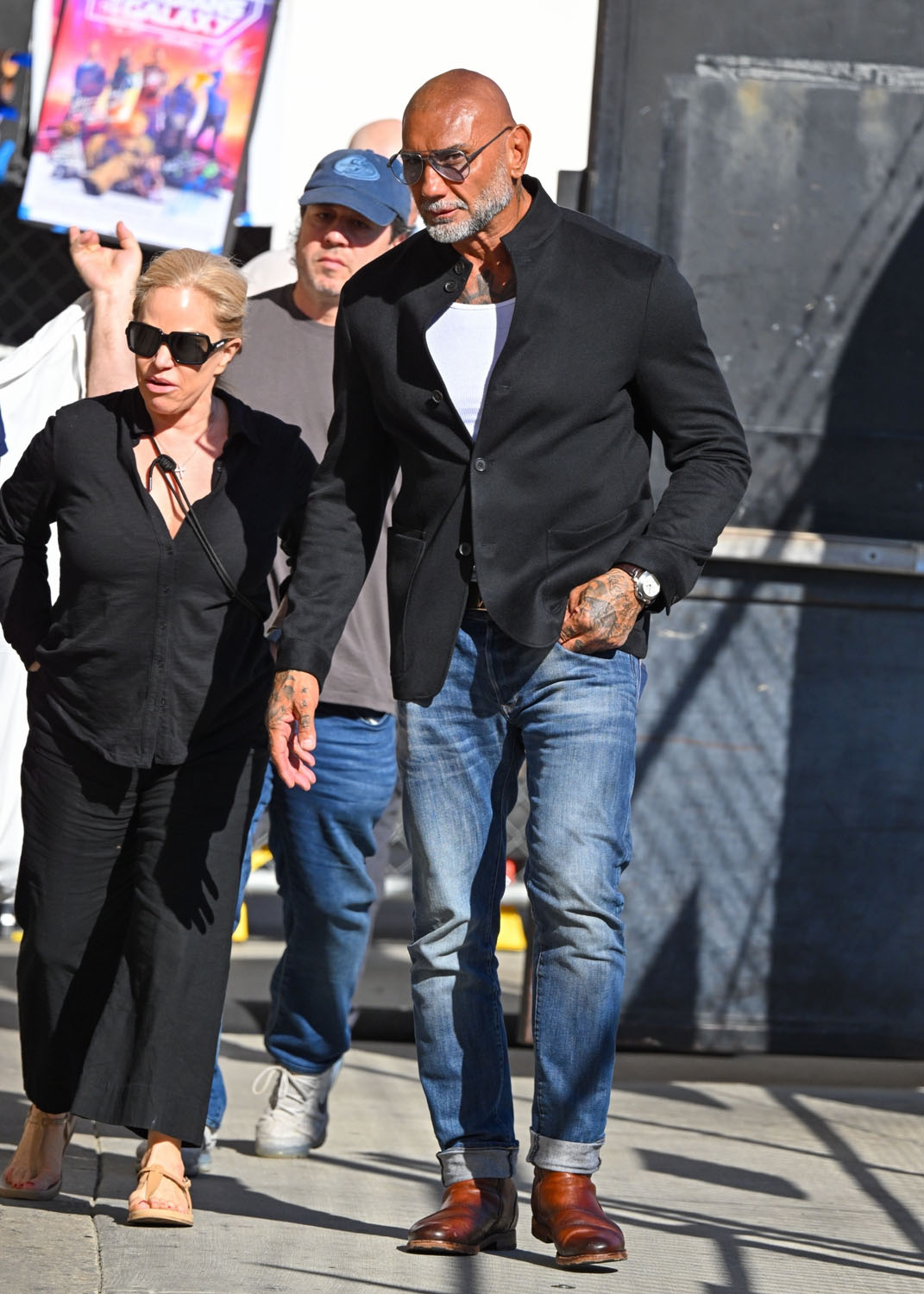

Dancing alongside Shelley are much younger dancers, including Jodie (Kiernan Shipka) and Marianne (Brenda Song). They do not have Shelley’s romanticism for their job and seem bemused by Shelley’s insistence that once upon a time, being a Vegas showgirl meant trips around the world and being treated like a star everywhere you go. But one night the show’s stage manager, Eddie (Dave Bautista), announces that the show will close in two weeks, which means Shelley, who has spent her whole professional life dancing in Le Razzle Dazzle, will have to find a new job.

The Last Showgirl is incredibly economical, both in its storytelling and its runtime (a lean 85 minutes). For the most part, these characters feel tangible, and the hand-held camerawork (overseen by cinematographer Autumn Durald Arkapaw) puts us in the midst of the dancers, as if we are one of them, sharing these moments backstage and at home. The intimate perspective only heightens the emotional vulnerability of the performances, particularly from Anderson and Bautista, who is also doing career-high work (with the bonus of a truly incredibad 80-styled wig). Jamie Lee Curtis also does great work as Annette, a dancer turned cocktail waitress, and Billie Lourd is a ball of resentment and hurt as Shelley’s semi-estranged daughter, Hannah.

The scramble to find new jobs reveals how far out of step with modernity Shelley really is. She cringes from the overtly sexual dance routine Jodie auditioned with for another show, declaring she could never do it, and she shuns the “dirty circus” that’s taking over their hotel theater space. Though she’s been dancing topless for almost 40 years, Shelley is prudish when it comes to modern depictions of sex, she sees Le Razzle Dazzle as the last connection to the French tradition of cabaret and burlesque, and she obsessively watches old musicals with their elaborate dance numbers at home. Of all the challenges to Shelley’s dream of dancing, her own perception of herself, Vegas, and the world is one of the greatest.

Amidst career turmoil, Shelley is also trying to reconnect with Hannah, who is about to graduate college and has her own dream of pursuing photography, though everyone else in her life encourages her to do something more realistic. Shelley is the only person encouraging her to pursue her passion, but looking at the time-warp bubble Shelley lives in, one wonders on what leg she’s standing to give out life advice. But what unites all these women across generations is sharing a dream to pursue their creative passions, even if it means doing degrading dance routines in a new show or embarking on a financially unstable career path.

The Last Showgirl mines its richest material when exploring the cost of those dreams. Shelley has little to show for her long career as a dancer; Annette is even worse off. And it’s not just financial, Shelley put dancing above everything and everyone else in her life, which means the loss of Le Razzle Dazzle isn’t just the loss of a paycheck, it’s losing the thing that has defined her more than anything, even her relationship with her own daughter. At the heart of Anderson’s performance is the pain of sacrificing everything for a dream that gives nothing in return. The Last Showgirl is in turns an angry screed against the way women are treated in the world, especially as they age, and a bleak meditation on the solipsistic pursuit of dreams. The Last Showgirl offers no comfort. Some dreams demand everything, and only you can decide if it’s worth it.