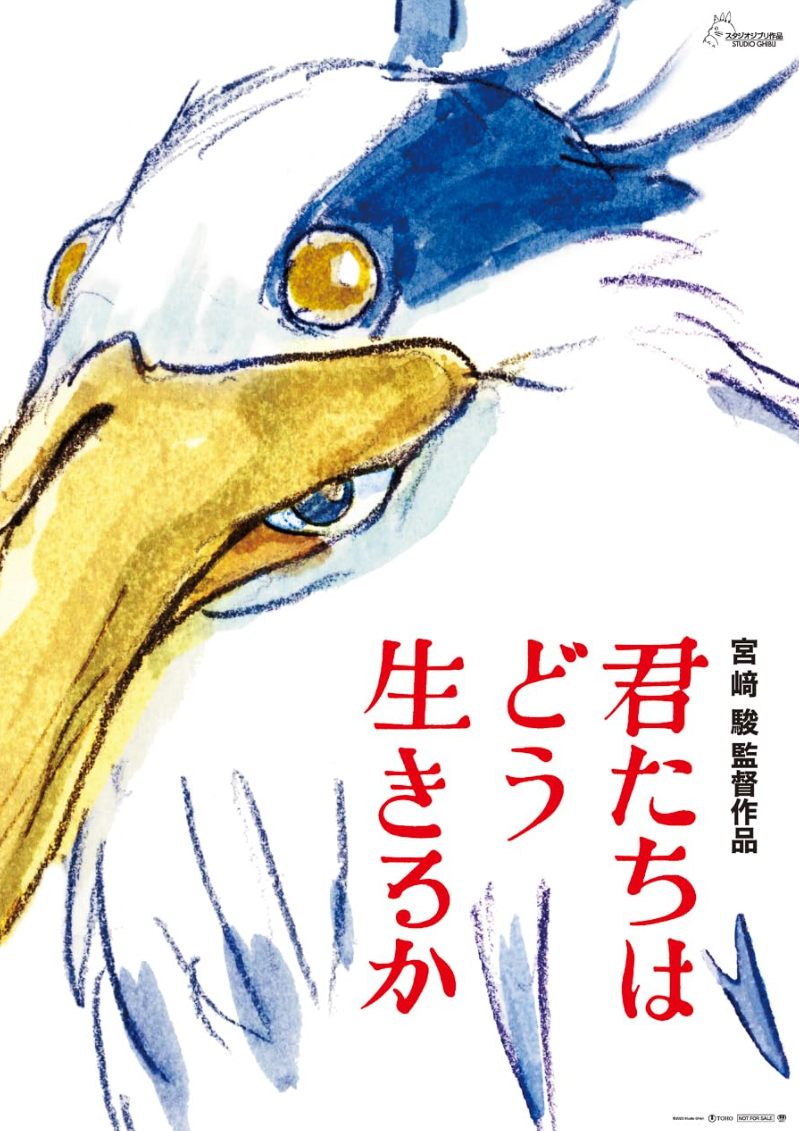

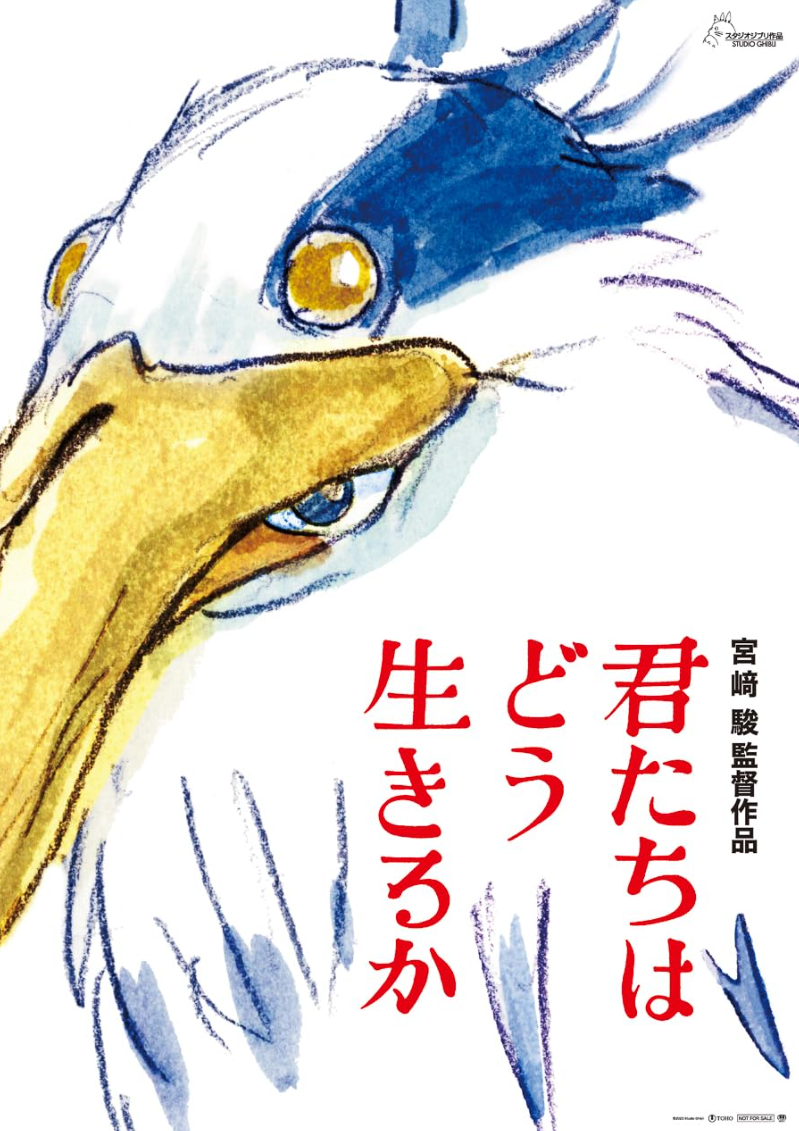

TIFF Review: The Boy and the Heron

Legendary Japanese filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki, co-founder of famed animation house Studio Ghibli, has not made a feature film since 2013’s The Wind Rises. He was believed to be retired, until earlier this year, a new film opened in Japan with virtually no fanfare. Kimitachi wa Dō Ikiru ka? (How Do You Live?) opened with no trailers or advertisements, only a lone poster to support it. It went on to become Studio Ghibli’s biggest opening ever and grew into a true grassroots hit over the summer. Now retitled The Boy and the Heron—for some unknown reason—Miyazaki’s surprise, latest film opened the 2023 Toronto International Film Festival, continuing its triumph among audiences as the biggest opening night gala TIFF has seen in decades.

And it IS a triumph. Heron is, if not perhaps Miyazaki’s final film, then a culmination of his lifelong creative exploration of childhood, growing up, and the inherent contradictions of living. Written and directed by Miyazaki, truly a living master of his art, Heron draws from his own experiences losing his mother, and as a boy during World War II. (For the “there were no Japanese people in Oppenheimer” crowd, here is an entire film by Japanese artists about the Japanese wartime experience.) Mahito (Soma Santoki) is living in Tokyo when his mother, Hisako, is killed in a hospital bombing. Mahito’s father, Shoichi (Takuya Kimura), removes them to the countryside, where he oversees a factory making parts for fighter planes, and has remarried Hisako’s younger sister, Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura).

Mahito is less than pleased by these developments and goes to rather extreme lengths to get out of going to his new school, where the boys are cruel. But at his new home, Mahito makes a series of wonderous discoveries. Within the grounds of their expansive country estate is a “nosy heron” who seems to speak and taunt Mahito with the possibility of his mother surviving, and there is a mysterious, run-down house in the forest from which Mahito is forbidden. One day, seeing Natsuko, who is pregnant yet ill, wandering into the woods, he follows her and finds a whole other world through the mysterious house.

As always, the animation of Studio Ghibli is beautiful, the style matching the fancifulness of Miyazaki’s story. Heron is, like much of Miyazaki’s later work, quite dark for what is ostensibly an animated children’s fable, but like The Last Unicorn—a very Miyazaki-esque film, though it predates most of his filmography—the film works on multiple levels. Though not suitable for very young children, there is enough whimsy and fancy to satisfy the younger audience. The happy, pillowy warawaras, for instance, seem designed specifically for youngsters, and the army of carnivorous parakeets are straight out of Alice in Wonderland. And adults can peel through the many layers of meaning and metaphor to unfurl a story about growing up, letting go, and forgiving—ourselves and others—that rings with the deep empathy of the elderly for the young inheriting a more f-cked up world than they intended to leave behind.

The heron himself is a mystical creature, a foolish, borderline trickster figure revealed as a man in a bird suit. The sight of an elegant heron speaking with human teeth is deeply upsetting, but that aside, Mahito’s journey is aided by the heron, one of the silly old grannies who occupy his new home, the adventurous Kiriko (Ko Shibasaki), and Himi (Aimyon), a young woman with superpowers. He also meets his great uncle (Shōhei Hino), who disappeared years before and is now ruling the magical land.

Legacy, destiny, self-determination, all of these things mix in The Boy and the Heron. The meaning is slightly in the eye of the beholder, as different thematic elements play more obviously depending on your own emotional baggage, but Heron seems especially imbued with meaning about one generation’s legacy to the next. You could interpret it as Miyazaki recognizing he has no real successor, but that his work has inspired and will inspire future storytellers to pick up the threads he leaves dangling. Or maybe it’s a morality tale about growing up and learning to recognize the needs of others. Or maybe it’s just a whimsical adventure, full of strange places and stranger people—er, parakeets.

Whatever you see in The Boy and the Heron speaks to your own experience, and, as always, merely whispers of the intentions of a master storyteller returned to regale his audience with a tall tale one last time…for now.

This review was published during the WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes of 2023. The work being reviewed would not exist without the labor of writers and actors. The Boy and the Heron will be exclusively in theaters from November 22, 2023.