Point Break at 30

Today marks the 30th anniversary of one of American action cinema’s most iconic films, Point Break. So welcome to Point Break Week! We’ll be revisiting the film over the next few days and the reasons why it continues to appeal, and is still so beloved, after three decades.

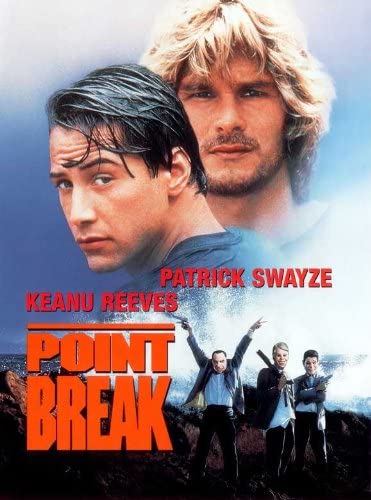

Written by W. Peter Iliff (from a story by Iliff and Rick King), and directed by Katheryn Bigelow, coming off the criminally underappreciated Blue Steel, Point Break emerged from the wreckage of the 1980s cocaine hangover with a dumb, coke-approved plot and a purely 90s, post-modern approach to action storytelling. The enduring appeal of Point Break is not just the magnetism of Patrick Swayze and the ethereal beauty of Keanu Reeves; it’s not just the bonkers plot and sporadically, unintentionally hilarious dialogue; it lies in the combination of dynamic action and surfer Zen philosophy, and the pairing of two classic Movie Stars, one established, one rising, who have become iconic in the Hollywood lexicon. Many movies have tried to capture the particular magic of Point Break, including a 2015 remake, but none have ever matched the combination of Bigelow’s technically accomplished filmmaking and critical eye toward masculinity, and the pure neon-lights power of Swayze and Reeves. Point Break is like a perfect wave: rare and unrepeatable.

On a basic story level, there is no defending Point Break. It’s a stupid movie that practically reeks of a cocaine-addled pitch meeting. A former college football champ named “Johnny Utah” who becomes an FBI agent and then is tapped to go undercover to bust a ring of surfing bank robbers is too many things happening at once. Take at least one thing out of this plot and the dumb quotient drops immediately. But Point Break is smart about the ways in which it is stupid, because while the log line is a LOT, everyone is taking it deadly seriously, and Bigelow’s approach behind the lens is no less determined and critical despite the pure silliness of the setup. The dramatic stakes, overloaded with brow-raising descriptors as it is, rise tangibly throughout the film as Agent Utah (Reeves) and his partner, Pappas (Gary Busey), close in on bank-robbing ringleader and surfing Zen master Bodhi (Swayze) and his gang of robbers in president masks. There is a constant sense of propulsive forward motion throughout Point Break that coalesces with the climactic showdown on the tarmac of Santa Monica airport. The conflict between Utah and Bodhi is inevitable from their first meeting, the respect that develops between them only makes it bittersweet.

It’s that combination of silly and smart that has made Point Break so enduring. It has rip-roaring lines that invite reciting, like “I am an EFF BEE EYE Agent!” and “Speak into the microphone, squid brain”, but it also has a chase scene of such precise technical execution it remains one of the best in Hollywood cinema – yet even that immortal chase scene includes an inexplicable moment in which Utah drop-kicks a dog. The chase scene encapsulates Point Break’s stupid-smart approach to filmmaking. Even when the film is at its dumbest, Bigelow’s direction, aided by cinematographer Donald Peterman and editor Howard Smith, is sharp and kinetic, imbuing the film with a muscularity that has become Bigelow’s calling card. This is a great-looking film, even 30 years on, and that is due in large part to the well-crafted action. A good chase scene, well-choreographed fights, moments of surprising brutality, these things don’t go out of style even if the clothes and music onscreen do. The fashions shown on screen have changed, but thanks to Bigelow’s direction, Point Break remains as watchable today as it was in 1991.

But Point Break also owes its timelessness to its two Movie Stars, Patrick Swayze and Keanu Reeves. Between them, Reeves takes more hits for his acting, though he is not a bad actor and his performance in Point Break is not bad. Reeves is a specific actor, keyed into a frequency that only sometimes jives with audiences. The exquisite Angelica Jade Bastien refers to his “thematic exploration of loneliness”, and I believe he has a suggestive sadness that bleeds into his performances and informs his characters. When Utah says, “Why can’t I ever say what I mean?” you feel his frustration in your bones. Likewise, you thrill along with him when he sky-dives, and his desperation is yours when he clashes with Bodhi in the finale. Reeves may not deliver every line with perfect, natural inflection—though his off-beat line readings are part of his eternal appeal—but at every moment we feel for his characters. Johnny Utah is a ridiculous description on the page, but Keanu Reeves makes him a believable, sympathetic character.

Swayze is no less successful as the older, more dangerous Bodhi. Swayze’s resumé is littered with characters who have reputations as stone cold badasses yet carry themselves like philosophy professors. Bodhi is another of these archetypes: a bank robber smart enough and cold-blooded enough to evade the authorities for years and escape at any cost. Yet, he’s a warm, affectionate beach bum, too, dispensing surfboard wisdom and life lessons to any who will listen. His charisma and alpha mentality give him the allure of a cult leader, but his easy smile hides the danger inherent in a personality strong enough to inspire a cult. As played by Swayze, Bodhi is a cobra, mesmerizing, beautiful, and venomous. He is equally unpredictable, his pursuit of a life-affirming thrill making him, ironically, nihilistic. It’s not hard to imagine an alternate timeline in which the Ex-Presidents get away and Bodhi and his crew become the Nihilists encountered by the Dude just a few years later.

Point Break was conceived in the 80s and born in the 90s and is still engrossing in the 2020s, thanks to its unique combination of dumb fun and smart action. The silly premise is underpinned by exciting action and efficient emotional storytelling, and incredibly good-looking surf scenes are juxtaposed with the brutality of the finale. Point Break is not a lazy afternoon, background movie, it demands your attention from the moment it begins until the moment it releases you with that final, crashing wave. And though the premise is wild, the approach is grounded in Bigelow’s perspective on performative masculinity—more on that later—and a consistent, bittersweet tone. The film itself seems to echo Keanu Reeves’ own suggestive sadness, as if to say, in Bodhi’s mock-wise voice, that all of this is now and never and again and no more. Vaya con dios, brah.

Point Break is streaming on HBO Max, or can be rented on digital platforms.