Travis Scott reflects on the Astroworld tragedy

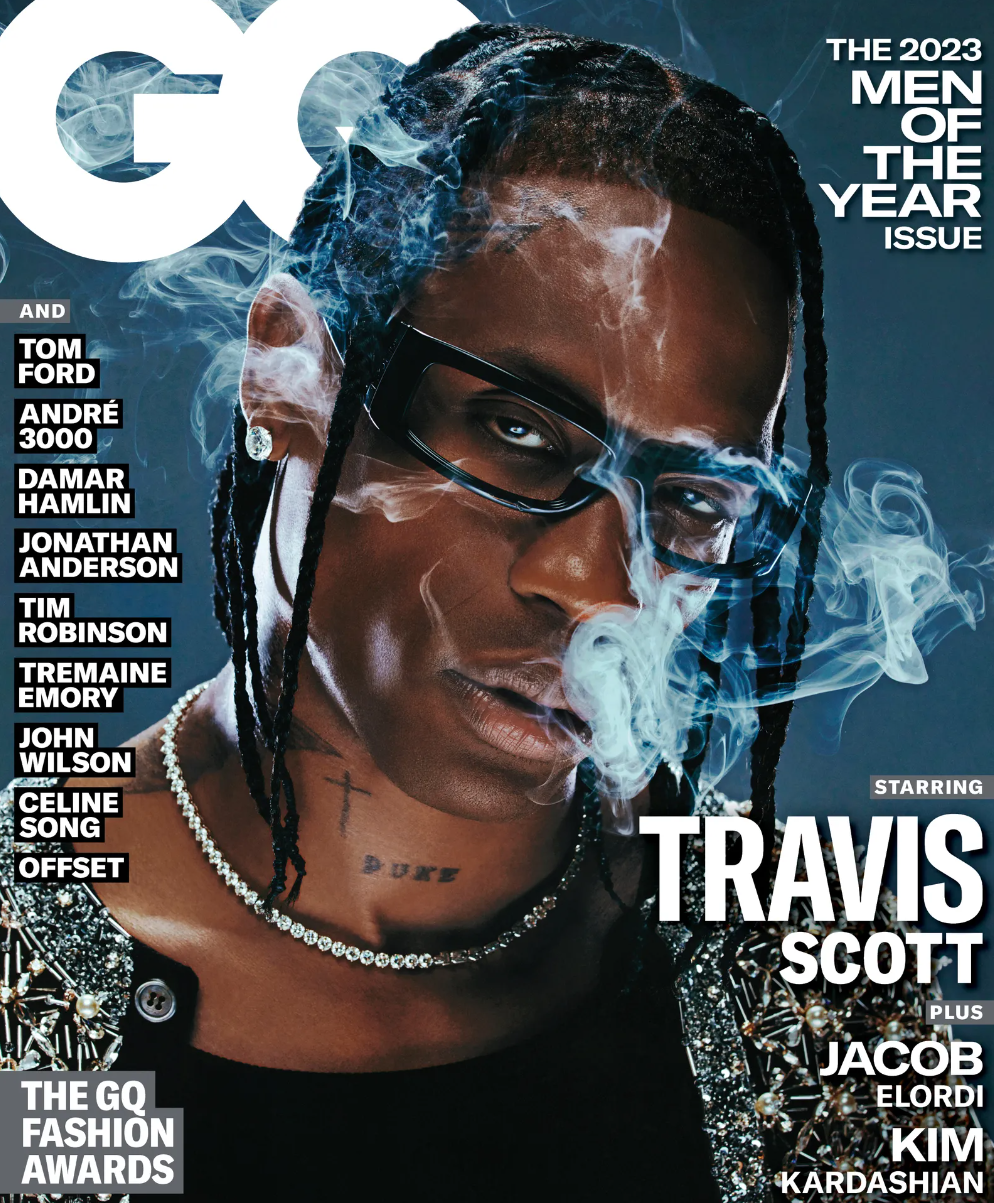

In an interview with GQ for their Men of the Year issue, Travis Scott reflected on the deaths of 10 concertgoers due to a crowd surge at Astroworld in Houston in 2021. In the interview, he described his thoughts about his fans, saying they were like “family” to him.

"I always think about it. Those fans were like my family," he said. "You just feel for those people. And their families."

The interview was wide in scope and delved into his childhood dream of being a nephrologist, to his role as a father. But somewhere in the middle, it turned to how the tragedy impacted the making of his latest album, Utopia, with Travis saying that it took a long time to get back to music.

"Making music, you think about things that go on in life and things that happen in your life, and you dial in on things. That moment for families, for the city, you know, it was devastating," he said, before going into detail about one song in particular, calling it his “favourite”.

In the song, called “My Eyes”, he sings about the tragedy that unfolded that night, and told the outlet that it addresses how he could be misunderstood, the “constant weight that’s put on” saying the song is a “vision” through his eyes.

He went on to say:

"I have pain, too. I have concerns, things that I think about, and the things that I see on a day-to-day basis, I think about them."

Though it’s great to hear him reflecting on this tragedy and not simply ignoring the fact that it took place, I had a very strange feeling reading this interview. Because though reflective, it still felt promotional. And for me, the juxtaposition of discussing something as serious as the loss of multiple lives at a concert, just two years ago, and a new album felt…well, it felt gross.

I suppose the question is – what is the “right”, non-gross way to move on from something like this as an artist? I think it’s natural that the music you make and even the way you make that music is going to be impacted by an event of this magnitude (see also: Pearl Jam, who considered splitting up after nine people died at the Roskilde festival during their set in 2000).

In Travis’ case, he was working on this album when the tragedy took place and had planned to release the first few songs during the festival, so it’s especially true here. But the question still remains - how do you continue on with your life as an artist, which requires the promotion of that music, while being sensitive to the horrific things that happened that night?

Despite several tragedies taking place at concerts and festivals in the last half century, it’s still not a question we have a definitive answer to. And while there is no handbook, so to speak, on etiquette that outlines how an artist should conduct themselves in the days, months and years following something like this, I think a lot of it begins with the role the artist played the day of the tragedy.

In the clips from the deadly night that were shared on social media, people had questions about whether Travis could truly see the severity of the situation.

https://twitter.com/jennelizabethj/status/1457151214316105731?s=20

Other clips emerged, including this one, where a concertgoer hopped up onto the platform where the cameraperson was filming Travis’ performance, calling attention to the worsening situation.

Footage captured at Astroworld shows two concertgoers trying to get the cameraman's attention to warn them of people being trampled during Travis Scott's performance. The cameraman filming Astrofest avoids them entirely.#astroworldfestival #AstroWorld #ASTROWORLDFest pic.twitter.com/zdBrUAuLST

— Βƌβƌβơ⊔⟟ℓℓ⋲ (@WulfMunkey) November 6, 2021

She later penned this first-person account of what happened that night, saying she was threatened with being pushed off the 15 foot platform if she didn’t go voluntarily.

In the days following the deadly Astroworld crowd surge, social media users hotly debated what the role of an artist is during a mosh pit. People shared clips of artists exercising crowd control by stopping their concerts to ensure the safety of the audience, such as this one of Linkin Park's Chester Bennington and Mike Shinoda.

No, THIS is exactly what’s supposed to be happening in a mosh pit https://t.co/fZQH0QiFuR pic.twitter.com/kWQdVBiShp

— linkeeen berrr ♠️ (@_LinkinBert) November 6, 2021

A clip from Australia Day in 2000 also resurfaced, with social media users praising the way the Red Hot Chili Peppers halted a concert to deliver a safety message.

Just one year later, nine people would die at that same festival.

What this says to me is that, despite the establishment of the “D barrier”, which was implemented after that deadly festival in 2001 to allow concert and festival organizers to ease potentially life-threatening crowd surges, not much has changed in the last 20+ years. Not in terms of mosh pit etiquette, not in terms of an artist’s role, and not in how an artist should govern themselves following something this awful.

I don’t think Travis is trying to be insensitive. I just don’t think there was a way for him to do this interview without coming across as insensitive. Had he ignored the mention of it completely, people would’ve dragged him. And addressing it in the way he did, relating it back to his music and creative process, makes it seem promotional. So who wins?

I think what we learn through hearing from artists after this kind of tragedy is that many things can be true at once. The awful circumstances that led to the devastation that night will have a reverberating effect on the families of the people who lost their lives that night, and I’d say for every person in attendance who is ever in a crowded setting again. And Travis can feel both shame and guilt – but also an innate need to deal with the nuances of his experiences in one of the only ways he knows how.

Perhaps that’s why GQ made him a selection. There’s a lot to dive into there. The article is certainly getting eyeballs, and not nearly as much for revelations about his childhood or parenting as much as it is people’s very keen interest in hearing what he has to say, two years later. Because there is a curiosity about what someone in that situation, someone in Ariana Grande’s situation, someone in Chester Bennington and Mike Shinoda’s situation, and someone in Pearl Jam’s or the Red Hot Chilli Peppers’ situation might do. It’s so unfathomable that it’s difficult to even hypothesize.

In the same way there’s no handbook for artists on how to make crowd surges less deadly, I don’t think there’s a handbook on how to handle the very complex grief and guilt that can come out of something like that. And so, though it may feel gross, it makes absolute sense that in a time of great discomfort, he resorts to talking about his music, and expressing himself through it. Because that’s what artists do.