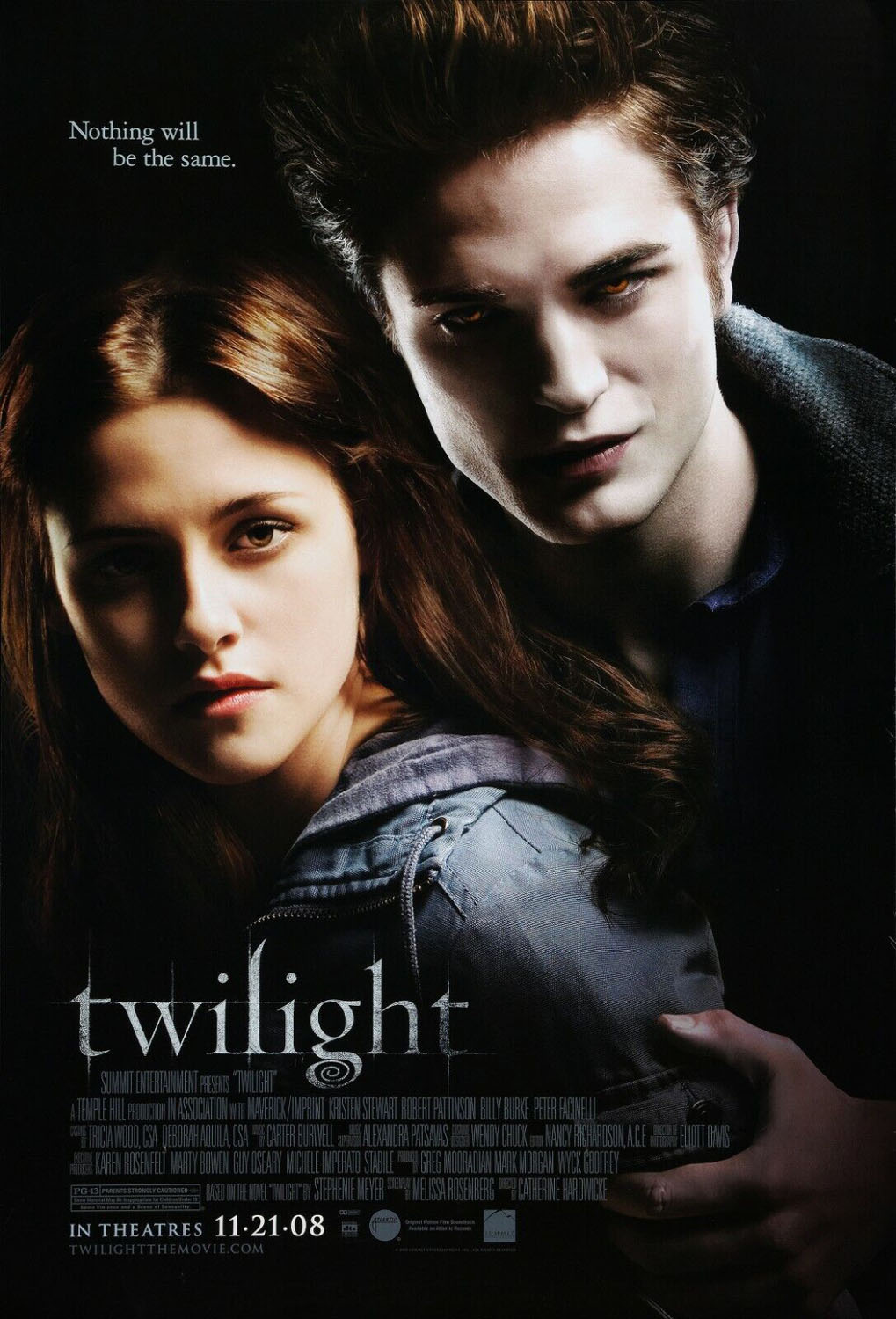

Twilight, 15 years later

Fifteen years ago, Twilight hit theaters, marking one of the 2000s’ seminal pop cultural phenomena. We’ve been talking—celebrating?—Twilight’s anniversary over on The Squawk all month (shameless plug to subscribe if you haven’t), but one main question lingers, and that is…how is the movie? Twilight premiered before I began my career as a film critic, and my lingering impression of the film is that it is very blue. So, I revisited Twilight, to see how it holds up and if it is really as bad as I remember it. And yes, it is as bad as I remember it, and also, very blue. But the benefit of a retrospective review is the context and kindness that time allows, and while Twilight is not a good movie, it’s not a total loss, either.

Compared to what came later, in the body of increasingly bland sequels and the highly derivative Fifty Shades trilogy, Twilight, while not good, at least has a soul of its own. Director Catherine Hardwicke, then best known for her teen dramas Thirteen and Lords of Dogtown, brings a little style and verve to an otherwise completely unhinged vampire romance that its own author, Stephenie Meyer, described as a sex dream, and it sure does seem like someone’s demented nighttime imaginings. Screenwriter Melissa Rosenberg, veteran of television series like The OC, Ally McBeal, and Party of Five, attempts to make sense of a narrative that almost completely defies logic, and she very nearly makes the central teen romance work in spite of itself. A lot of Twilight feels like an uphill battle against the source material.

Vampires have a long literary and cinematic history as metaphorical text laden with sexuality, from xenophobic Victorian fears of the other coming to seduce innocent English roses, to the blatant lust objects of the 1990s. By the 2000s, vampires had been Whedonized by Joss Whedon’s popular Buffy the Vampire series, and its spin-off, Angel, and vampires went from fearsome horror monster to sexy teen metaphor for puberty and pants feelings. Twilight then came along to suck all the sex out of vampires and render them beautiful but chaste furniture for a Cinderella story about a reader insert who is romanced by an elderly man who wants to eat her.

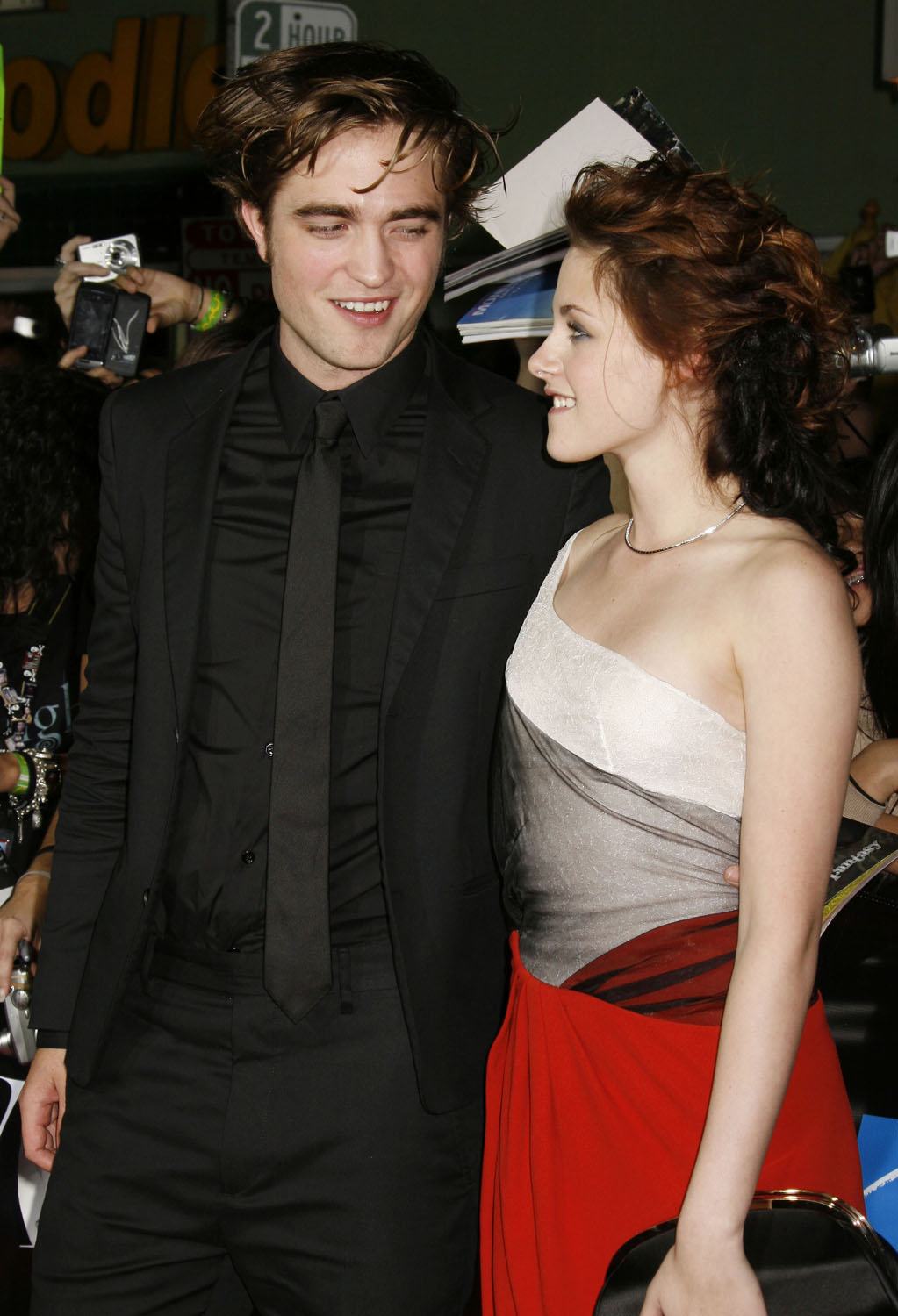

Twilight, of course, made superstars of Kristen Stewart and Robert Pattinson, and what holds up in the film is primarily their performances (and the music, from Carter Burwell’s appropriately moody score to the soundtrack, a perfect 2000s snapshot of emo rock). Stewart excels at playing Bella Swan, an awkward high schooler who doesn’t know she’s pretty and cringes from attention. Sent to live with her father in the remote town of Forks, Washington, she’s the new girl in school and an instant source of fascination for the other kids who live in Forks, a town that appears so small, incest must be a real concern.

Stewart also imbues Bella with enough blank-faced stupidity that it is 100% believable Bella would wander into the dense woods with a boy who has done nothing but stare at her like a serial killer since they met. At the time, Stewart’s performance was derided as bad acting, but I sincerely see her choices as deliberate. She plays Bella as void enough that a viewer can project themselves into Bella’s place in the narrative—the purpose Bella Swan serves in the books—and as dumb enough to willingly risk her life because a boy is cute.

Pattinson, meanwhile, plays vampire centenarian Edward Cullen somewhere between the frequencies of James Dean and dried Play-Doh. Like Stewart, he’s saddled with the herculean task of turning a badly written fantasy object into something watchable on the big screen, and he gets there largely on his own strange charisma and great hair. Pattinson has turned into one of the best eccentric actors working today, and his talents show through in his performance as Edward. As Pattinson portrays him, Edward is a combination of demented and controlling, a walking red flag that should send any sensible person screaming in the opposite direction. Despite his broody good looks, Edward cannot hide what a f-cking weirdo he is, it’s amazing he’s the most desirable boy in Forks, until you remember there are only, like, four other boys in Forks. Pickings are slim.

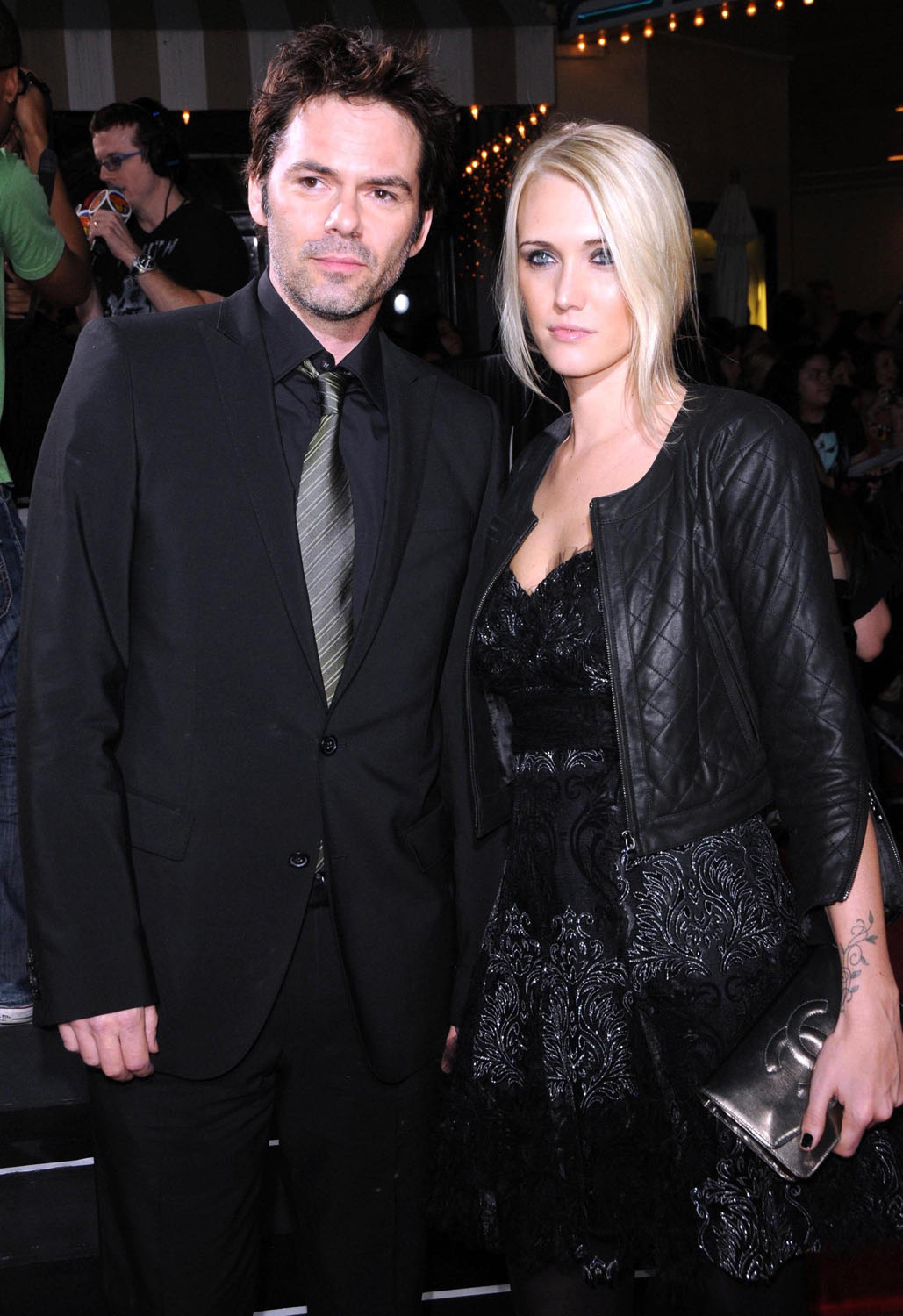

The rest of the cast does the best they can with the material they’re given, too. The standout was and is Billy Burke as Bella’s shotgun-toting dad, Charlie. He might be the single most unobservant cop in the history of the world, but he matches Stewart’s prickly energy and also brings a shy kind of warmth to Charlie, a father who clearly loves his daughter but doesn’t know how to parent (obviously, as his daughter flings herself at a vampire within five seconds of arriving in town). Taylor Lautner is also more charming than I remember as Jacob Black, a boy from the nearby Quileute reservation—Twilight’s Indigenous representation is abysmal, though.

For all that Twilight is derided for sparkling vampires, it does manage to contribute, for better or worse, to the canon of vampire lore. The sparkling is dumb, and the visual effect isn’t aging well, but these vampires are less about being creatures of the night than they are creatures of appetite. Edward and his found family of fellow vampires are “vegetarians” because they don’t eat humans, only animals, but they are hunters, nonetheless. Predator and prey imagery is rife throughout the film, and while the metaphor is simplistic, it is effective for a story about a girl resisting sex at the peak of raging teen hormones.

As much as everyone gets horny for Edward, Twilight is almost entirely chaste, a deliberate choice of the author that the filmmakers honor. Edward and Bella are horny balls of hormones who can’t stay away from each other, yet somehow resist tumbling into bed, as they would do in any other teen romance of the era. It’s hard to divorce this from Meyer’s real-life religious beliefs as a Mormon; impossible, in fact, Twilight could not have come from an irreligious person. The kindest read, then, is that Twilight is a vampire romance for the abstinence crowd (something the later books/films stringently reinforce).

Hardwicke pushes against this chasteness, though, highlighting desire through scenes laden with tension and the natural chemistry of Stewart and Pattinson. There are stares, people are pining and leaning. All of Bella and Edward’s interactions are fraught with want—a wanton amount of want, even—and the film’s core tension comes from the cognitive dissonance of acknowledging fervent mutual desire while still pushing Edward and Bella toward their purity ball impasse at prom. Vampires have long been associated with sex, but using vampires to tell an abstinent love story is an awkward fit which is a major reason Twilight never really clicks as anything deeper than a simple Cinderella fantasy.

But it’s not THAT bad. The entire “Bella’s first day” sequence is legitimately funny, thanks in no small part to Anna Kendrick’s bitchy charm as mean girl Jessica. The parking lot near-accident is a well-executed piece of action, and vampire baseball is iconic. Everyone is doing the best with what they have, which is a bad story and a low budget. Hardwicke gives the film some indie spirit, the performances are good, even the blue filter on everything (the film is lensed by Elliot Davis) suits the moody, rainy setting of Forks and highlights the unreality of Bella’s new life. Twilight feels slightly off kilter, not quite right, like a sparkling vampire standing next to Dracula, Nosferatu, and Lestat.

Twilight is not great art, but it is an interesting cinematic quirk, a lame entry into vampire lore that still finds a way to almost say something about burgeoning sexuality. It will be best remembered, though, for the careers it launched and, well, that’s enough.

Twilight is now streaming on Prime Video.