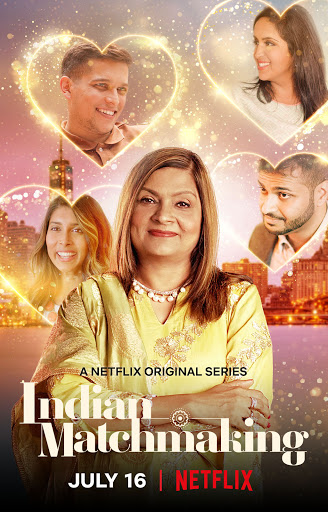

Unpacking Netflix’s Indian Matchmaking

It has now almost been two weeks since Indian Matchmaking showed up on our Netflix recommendations, and it still continues to be one of the most divisive shows to appear in Netflix’s lineup.

If you’re just hearing about Indian Matchmaking, where have you been? The show follows Sima Taparia, a professional matchmaker based out of Mumbai. She and her rolodex of single Indian men and women travel the globe to help wealthy families arrange marriages for their children.

Since its release, the show has elicited many strong reactions, with some thoroughly enjoying it and others decrying its light-hearted treatment of a serious issue, and many more both hating and loving it at the same time. BBC called it “cringe-worthy”. I for one cannot stop watching. Like everyone else, I’m floored by some of the things that come out of Aparna’s mouth, and I am fascinated by Pradhyuman, who, as Sonya Saraiya writes in Vanity Fair, “you wish someone on the show would simply ask...if he’s even interested in women.” I started watching the show this weekend with my parents. It’s actually a pretty good family show, particularly for Indian families. That’s because for many people of Indian descent, living both in India and North America, the arranged marriage rigamarole is a fact of life.

Arranged marriage has always been a familiar institution for me. My parents’ marriage was arranged, as were the marriages of most of my family. In fact, it’s a well-known phenomenon that once you reach a certain age, the matrimonial prospecting starts happening. “So and so’s daughter/son is looking. What’s your son’s horoscope?” For a while, I was anxious about it myself, although it turns out that being gay kinda short-circuits the whole system.

Different families practice arranged marriage in different ways. For some, it is simply a means of introducing two people who may have family or community connections. In such an application, it functions almost as Tinder: a curated list of potential dates. For others, arranged marriage is a family affair and a family decision. The push and pull of the current generation’s desire for independence against a strong tradition of family involvement in marriage planning has even resulted in a hybrid system. Family input is important and often the vehicle through which matches are introduced, but the final decision is up to the child. At least in theory.

What is almost always true about arranged marriage is that it carries with it the implication of a lifelong partnership. People are matched and date with the intention of getting married and starting a family, something that casual dating doesn’t really address. A casual Tinder date isn’t usually burdened with the evaluation of whether the person sitting opposite you will be a good parent, a responsible homeowner, and a lifelong partner. In fact, many people date with the understanding that the ensuing relationship probably won’t be their last.

I say this all to highlight the variety and complexity with which something like arranged marriage involves. To many, the unspoken pressure of marriage is akin to the days when children had no say in their relationships. It’s a burden especially carried by Indian women who are frequently expected to bend over backwards for their male suitors. To others, modern arranged marriages are a time-honoured tradition that has been updated to match today’s standards. It’s an efficient and structured way to create long-lasting partnerships that take into account all the messy requirements and quirks that come with the union of two families.

I think the reason Indian Matchmaking has been so divisive is because arranged marriage itself is a divisive issue. But in the limited field of Indian representation, Indian Matchmaking faces the brunt of criticism because it dares to take an uncritical approach to its subject matter.

Is that a fair assessment? In many ways yes. Indian Matchmaking does gloss over many of the issues rooted in colorism, sexism, and a rigid patriarchal system. However, Indian Matchmaking isn’t a documentary. It’s a reality show. One that lives alongside Too Hot to Handle, Love Island, 90 Day Fiance, and Love is Blind. Do we critique those shows in the same way?

To me, that’s because Indian Matchmaking is part of a larger problem in representation. Diverse shows are held to a higher standard because there are so few of them in the market. In a perfect world, this wouldn’t be the only widely consumed media about arranged marriage, and there would be opportunities to explore the complex and layered practice. Instead Indian Matchmaking has to present the reality of the situation, but also be critical of it, but also be entertaining, but also be authentic, but also fit a narrative, but also so many other things.

In Never Have I Ever, Kamala struggles with the idea of arranged marriage, wanting instead to emulate the bold declarations of love and independence seen in Riverdale. She too is expected to change herself and mold her behaviour to appease the parents of a boy. She also meets an older lady who feels ostracized by the community for marrying outside of her community and tells her not to do the same. Yet, Kamala later sees the value of being matched, telling us that it’s not all that bad. Why is that allowed?

Arranged marriage is complicated. It’s important to be critical of reality and the institutions that affect people’s lives. Many Indian women have shared their experiences and articulated the oppressive and traumatic nature of the arranged marriage paradigm.

I’ve been seeing a lot of jokes about the show on matchmaking and arranged marriages on Netflix and as someone who’s lived through this hell for most of her twenties, I’m here to tell you; it’s no joking matter 1/n

— nikita doval (@nikitadoval) July 19, 2020

I also don’t believe that we should wholeheartedly accept this show for what it is. As Variety noted yesterday, there was only one Indian person present on the key creative team, and Netflix India was not at all consulted while filming and producing the show. A company in Dubai handled all the onsite filming in India!

At the same time, it’s important to examine why we’re so critical of Indian Matchmaking, and why despite that, it’s still immensely popular. Clearly, there’s something of value there that draws in audiences and people like myself. Perhaps it’s because it reflects a familiar and well-known experience that many Indian audiences can relate to. But maybe, it’s also because in that reflection, we can finally see some of the imperfections and issues in a clearer light. Reality TV exaggerates life, but in doing so, it can also magnify issues and start difficult conversations. Can we say this about Indian Matchmaking?