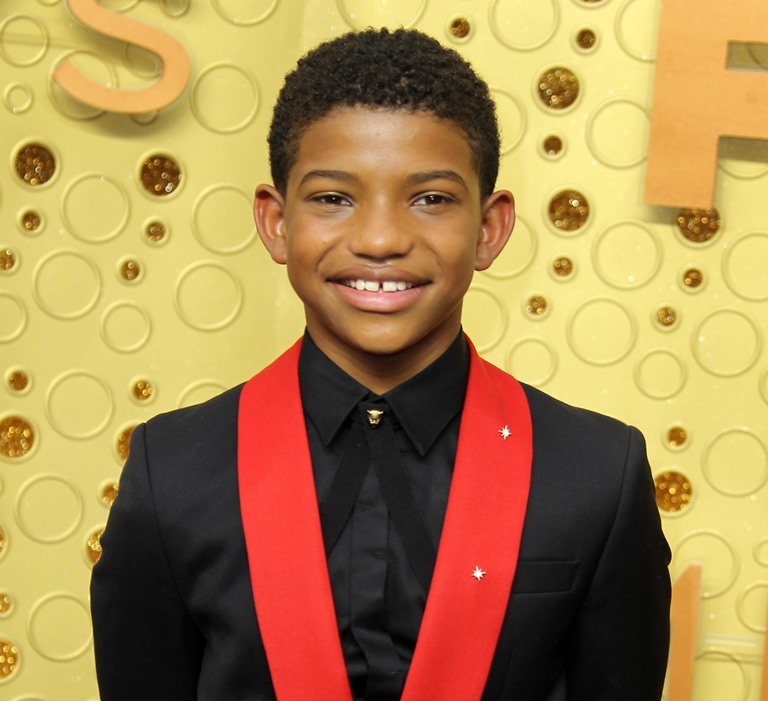

Lonnie Chavis: Growing up Black

Lonnie Chavis is one of the stars of This Is Us, he plays the young version of Sterling K Brown’s character, Randall. He has written an essay about the experience of growing up Black, and please, particularly if you are not Black or Indigneous, please read it because right now, these are the stories that should be urgently heard, these are the stories that have NOT been heard, because whiteness has been the dominant culture, and the white perspective has dominated storytelling – and we are finally (wayyyyyy too late, as Black and Indigenous people would point out) seeing the dangerous, tragic consequences of valuing white stories over others. Kathleen said recently that Black people are tired of having to fight for their humanity, like on a Tuesday. This statement directly speaks to empathy, who we have been conditioned to empathise with and who we don’t. And there’s a relationship between that and which people and experiences we center in storytelling.

Lonnie is 12 years old. He’s not a man but he has heartbreakingly already been made into a man because he is growing up Black, because he has seen his father arrested and physically abused by police on their doorstep on a simple traffic stop. Because he has seen his mother pulled over because the police didn’t believe that they could afford a nice car. Because his mother then told him to stay quiet and not object, otherwise he COULD DIE. He has been witness to this and he’s ONLY 12. And all of these observations started when he was much younger. Which means that Lonnie lost his innocence a long, long time ago.

All parents want to preserve the innocence of their children. But innocence too has become a privilege. Because the moment a Black parent has to have “The Talk” with their Black child, and this happens when they are under ten years old, they know that they are taking away their child’s innocence. Imagine the heartbreak of having to perform this responsibility? Imagine how sh-tty that must be? The conflict that exists inside every Black parent who wants to instill in their child a sense of hope and possibility but also must balance that with reality, with preparation, because they know that the world will not be kind and, most importantly, they know that their child might die as a teenager for simply walking around wearing a hoodie? Non-Black and non-Indigenous parents don’t have this burden. But many are starting to think about how to communicate and educate their children now to better understand the experience of their kids’ Black and Indigenous peers – that is if they even have any.

To go back to Lonnie though, consider the reason why his essay is being published in PEOPLE. This is a magazine for the MiniVan Majority. These are white women, many of them with kids, who could benefit from reading a Black child’s story…because then it becomes harder to bring up the bullsh-t “buts”: “but he was resisting arrest!” “But he had a record!” But, but, but, but, BULLSH-T.

There’s no “buts” where a 12 year old boy is concerned though. You can’t “but” his story. Anyone with any decency should understand that this child should never have seen the things he’s seen, that he should never have the fear he carries around every day. And the thing is, the monsters aren’t just the white robe-wearing assholes. The monsters can sometimes be the people who mean well, the ones who are supposed to give him a safe space.

Because in his piece, Lonnie describes an incident on set. They were shooting a scene where an actress playing a racist is being racist. Lonnie begins to cry which they didn’t call for in the script. His reaction was natural, he was reacting in pain to the reality in the fiction. And he was told he didn’t have to cry by people who didn’t understand that even being a part of that was traumatic. That is white privilege.

Earlier this week, on the latest episode of Show Your Work, Duana and I talked about how barriers to creativity specifically in the context of racism and white privilege. This is an example. Lonnie shares that, “The director and writers told me that they didn’t need me to cry for the scene.”

That’s a creative decision and it’s one that clearly ignores the Black experience. Click here to read Lonnie’s essay.