This is a conversation about consent

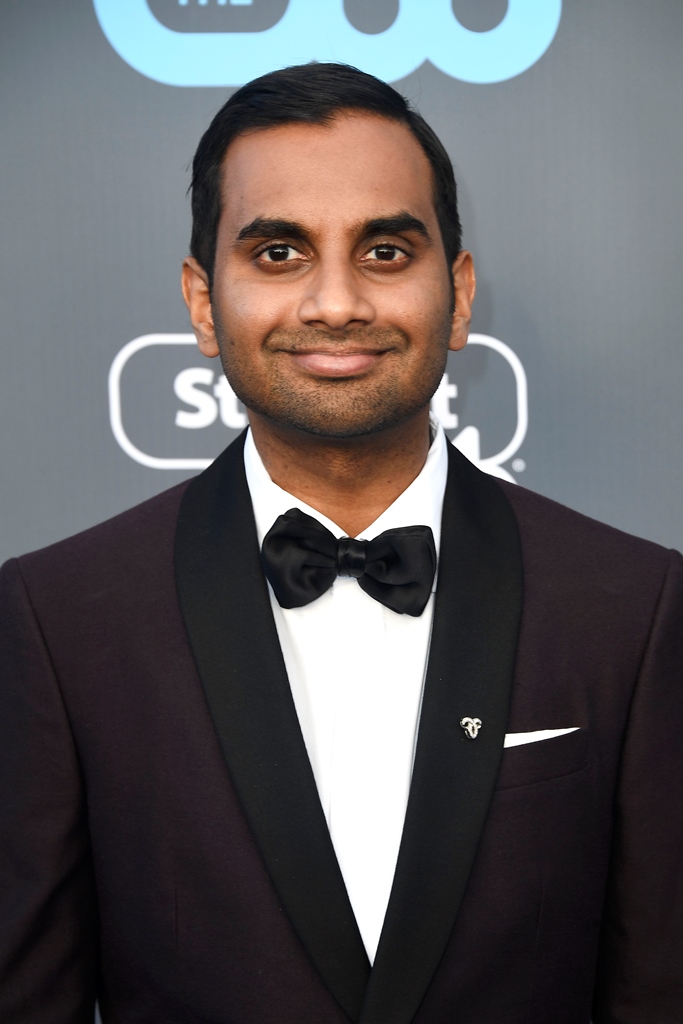

Over the weekend, a story about Aziz Ansari was published, in which a woman referred to as “Grace” recounted her date with Ansari, which ended in his apartment and a moment far too many women know: A round of touch-roulette where you try to decide the least awful places and ways to let this person touch you because you’re not getting out of the night without letting him touch something in some way. Many of us with similar experiences have described this in the past as a “bad date”. Grace calls it “sexual assault”. There’s an entire conversation happening about if Grace’s experience does or does not qualify as assault, and all the usual filters are being applied. The greatest hits include “She agreed to the date”, “She went back to his place”, “She took off her clothes”, and the chart-topping remix of “She was asking for it”: “She didn’t say ‘no.’” If you’ve heard yourself say any of these things in the last few days, maybe ask yourself what you’re really excusing, and why.

Because this is not a conversation about what does and does not qualify as sexual assault. (But I would remind you that Convicted Rapist Brock Allen Turner’s father dismissed his violation of an unconscious woman as “twenty minutes of action”, so what does not qualify as sexual assault is wide open, and maybe that conversation needs to start with the question of whether or not our current definition of “sexual assault” is too narrow.) This is a conversation about consent. At the end of the day, ALL of these conversations are about consent. Grace gets to process her experience however the f*ck she wants, I’m not here to judge her life. I am here to listen. And all I hear, over and over again, is the consent of women being violated, sometimes in violent, scary ways, but a lot of the time in regular ol’ every day ways we all recognize.

Grace’s story is hard to hear. It’s another beloved figure—someone who makes us laugh!—taking a tumble off the Woke Bae Pedestal. We’ve been here before. But it’s also hard to hear because so many of us can relate to it. (Insert “Men are just way worse at sex than they think” joke here.) And it’s hard when these stories hit home. It makes us remember things we might not want to remember. Makes us reassess something we’ve already processed. “I’ve had bad dates and don’t think it was assault,” perhaps you’re saying that to yourself right now. Cool. You get to process what you go through however you want. We shouldn’t be tearing each other apart over how we deal with the things we experience. We should be talking about the common element of ALL of our experiences, and that is a lack of consent.

As women, we live our lives prepared to have our consent disregarded. There’s a whole checklist of things we do to protect ourselves because part of the condition of being female is accepting that you are prey. The list is ever-evolving, ever expanding, based on our experiences. I stopped wearing skirts/dresses on dates after a guy put his hand up my skirt in a restaurant. Then a guy put his hands down my pants. Then another guy tore my jeans—seriously, think about the force required to tear the fly out of a pair of jeans—and now I don’t know what I’m supposed to wear for a date. Trash bags? Still working that one out. But I’ve got other tricks, like “don’t give him a real number” and “don’t let him pick you up/drop you off”, a lesson learned after I declined a second date and the dude sat outside my building until I would explain to him, in person, why I didn’t want to go out with him again. “This conversation is why,” I said, and he spat at me and called me a bitch.

Sarah, you have such bad luck! Do I? Because every woman I know has at least one story like this. If you don’t have a story like this, you are very lucky and I genuinely hope you never do. Grace now has a story like this. She met a guy, she was dazzled and into him and he was into her, and they went out, and it didn’t end well. It made her feel bad. She described behavior a lot of us recognize—placating, defusing, even playing along to stop something bigger from happening. Her consent was ignored, because it was never asked for.

Men are taught “no means no”, but that is only half the equation. The other half of the equation is “ask for yes”. Don’t just wait for a “no”—because odds are, if it gets that far, the moment has already turned violent and it may well be too late to stop sh*t happening. Aziz Ansari has built his career on being a sensitive, thoughtful ally to women in a dating era complicated by technology. But he’s still a product of the “no means no” generation, where consent is portrayed as only relevant to violent attack. But consent isn’t just about violence, it’s about sex, period.

That we’re so hung up on defining Grace’s experience is ignoring the issue of consent, which is where the night went wrong in the first place. And Ansari’s statement doesn’t help because he’s still pitting his wants against hers (instead of seeing their sexual encounter as a partnership based on enthusiastic consent). He says, “We went out to dinner, and afterwards we ended up engaging in sexual activity, which by all indications was completely consensual.” Except it wasn’t, because Grace’s story is about how he ignored her physical discomfort and non-verbal cues, and attempts to redirect their activity. He was waiting for a “no”. He never asked for a “yes”.

We learn to keep our hands to ourselves in kindergarten. And then, at some point, half the population is tacitly given permission to touch the other half of the population whenever they want, however they want, and regardless of what the other person wants. And that, really, is all this is. All of it, the whole conversation, this is what it boils down to: Consent, and the disregard for and lack thereof. The burden must shift from waiting for a “no” to asking for a “yes”. “No” is a word so inherently dangerous many women do everything in their power to avoid saying it outright anyway. But “yes” is a word everyone likes. It’s a word of action, it’s not lack of resistance but willful engagement.

But right now the entire, crushing weight of preventing EVERYTHING, from violence to unwanted attention, falls on women. It’s an untenable burden, living in a world where you are responsible for your physical and sexual safety every second of every day, which is why there are so goddamn many victims in the first place. Because it CANNOT be done. It is impossible. And we fail. And we are victimized. However you want to parse it, whatever scale you want to apply, that’s your own thing and I’m not interested in the semantics. What I am interested in is lessening this burden. And it begins with asking for “yes”.

If you haven’t already, please click here to read about Grace’s experience.