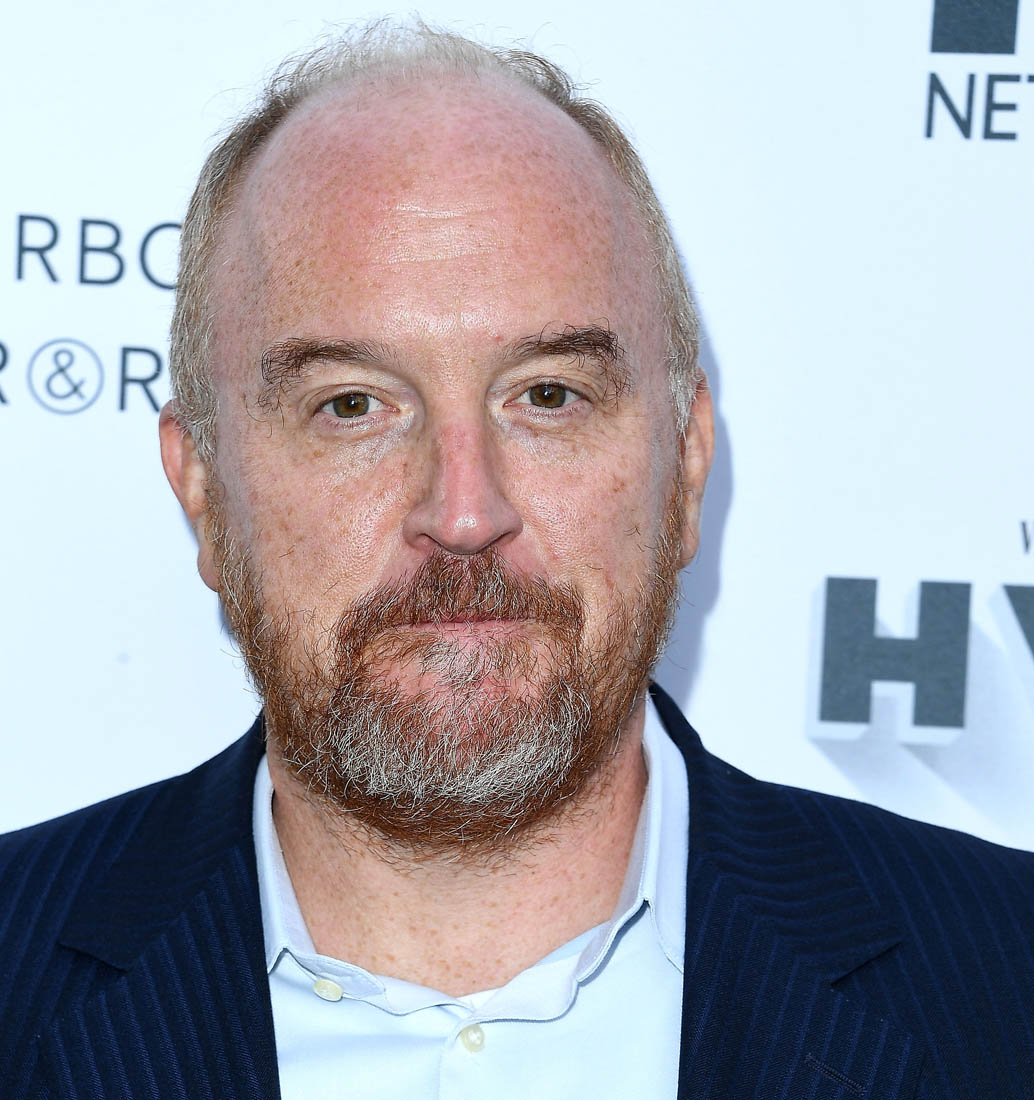

I’m more disappointed in myself than Louis C.K.

In 2012 rumors began with a Gawker blind item that identified a “beloved comedian” who, allegedly, jerked off in front of women, citing an incident at a comedy festival involving two female comedians. It was widely believed to be Louis C.K. (Gawker would eventually explicitly name C.K.) Those rumors were given new fuel recently when Tig Notaro made clear that despite receiving an executive producer credit on her show, One Mississippi, C.K. is not and never has been involved. “He has nothing to do with the show,” she emphasizes repeatedly in an interview with The Daily Beast. She goes on to say, “I think it’s important to take care of that, to handle that, because it’s serious to be assaulted. […] It’s serious to be harassed. It’s serious, it’s serious, it’s serious.”

This is the strongest and most pointed criticism levelled at C.K., because Notaro isn’t just a gigging comic in the clubs—though they have spoken up, too— her introduction to mainstream audiences came because C.K. sold her incredible 2012 set in which she began by announcing, “Hello, I have cancer," through his website." Notaro and C.K. are peers, and while she doesn’t owe her career to him, there is a professional connection, a relationship, even. So it was surprising to hear Notaro speak so sharply about C.K., and to reveal they haven’t even spoken in years.

As Emma Healey points out in her tremendous essay for Hazlitt, the rumors about C.K. remain nebulous. No one has officially attached her name to specific allegations. Jen Kirkman came closest, but she walked back her comments. (Roseanne Barr also walked back comments she made about C.K.) And as Healey writes, this makes it easy to dismiss the allegations, or at least ignore them, especially because C.K. won’t talk about it, either. In an interview with Vulture last year, he said, “I do the work I do, and what happens next I can’t look after. So my thing is that I try to speak to the work whenever I can. Just to the work and not to my life.”

When it first came up in 2012, I thought, Oh please don’t be Louis C.K. But the rumors never went anywhere, so I put it out of my head. When it came back in 2015, I thought again, Please, not him. I confess to taking the easy way out, not disbelieving the women speaking up, but just not…wanting to hear it. But this time, it was harder to ignore, because C.K. was wrestling with issues of misogyny and harassment/assault and the myriad ways men hurt women.

In his 2013 special, Oh My God, he talks about the threat of men and violence against women. And in his show, Louie, Louie—played by C.K.—assaults his friend Pamela. His new film, I Love You, Daddy, is about a father, again played by C.K., wrestling with an admired filmmaker who expresses interest in his underage daughter. Women, misogyny, violence, assault—these things were on C.K.’s mind so much they infiltrated multiple mediums of his art. I do not miss the awful irony, that what forced me to start examining my relationship with C.K. and his work were his own words, and not the words of alleged victims. It’s inexcusable, and there is no defense.

What finally broke the mental and emotional stalemate I was in came late last year. I was defending my decision to be done with Woody Allen at a party, explaining how I can no longer separate art and artist, especially when his art dares me to keep making that excuse. I said I was tired of men being excused no matter how awful the accusation just because people enjoy their work. And then I heard myself, and my mind leaped to Louis C.K.

When I got home that night, I went through everything I’d written about C.K.—I had reviewed his show Horace and Pete earlier in the year—and I hated myself a little. Because I knew by then something was wrong, that there was and is a serious issue surrounding C.K., and I had refused to engage with it in a meaningful way. As a critic, I wasn’t doing my duty. As a fan, well, I was being a coward.

When TIFF came around this year, I didn’t put I Love You, Daddy on my list of potential reviews. It was still the coward’s way out, and I still didn’t want to engage with C.K., the rumors, my loss of admiration in and enjoyment of his art. But I didn’t say anything about Joss Whedon, another personally upsetting loss of respect, so when a reader named Madelyn asked for my take on Emma Healey’s essay, it was like a personal challenge—talk about this now, or forever lose not only respect for C.K., but for myself, too.

So, my take—I’m disappointed. In C.K, sure, but mostly in myself. For choosing my own entertainment and shallow enjoyment over a woman’s trauma, for hearing but refusing to listen, for contributing to a culture that silences and hurts women. I never told anyone to sit down and shut up, but I also didn’t choose to amplify, and my selfish refusal to empathize keeps an alleged harasser in a position of comfort and power. (Is my voice so strong? Not alone, no, but how many people made the same self-interested choice?)

So I join Tig Notaro in saying that Louis C.K. must address these rumors and allegations directly. It’s not enough to tease it obliquely through his art. This is, as Notaro says, a serious issue, and it deserves to be treated seriously, by everyone. Refusing to participate is a luxury. Picking and choosing what to talk about—controlling the conversation—is a privilege. It’s one I can no longer in good conscience afford myself. I only wish Louis C.K. would do the same. But he probably won’t. They never do.