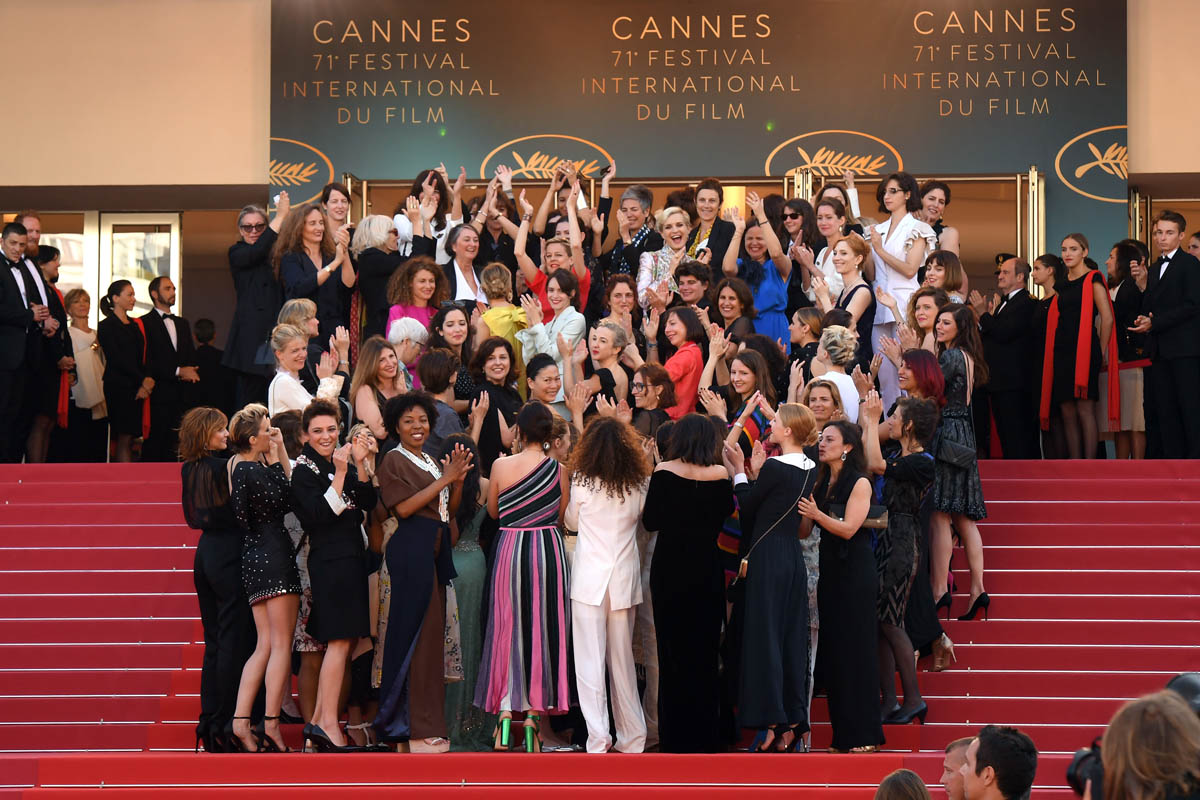

The Cannes Women’s March

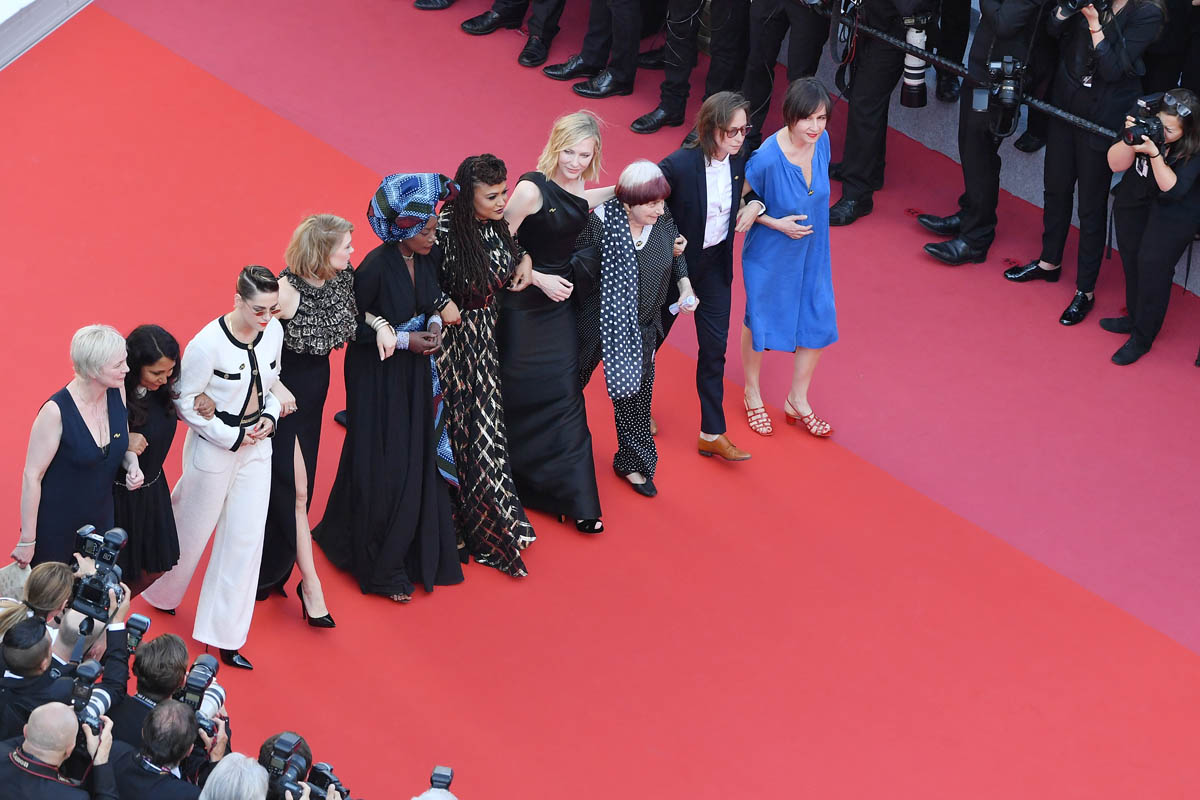

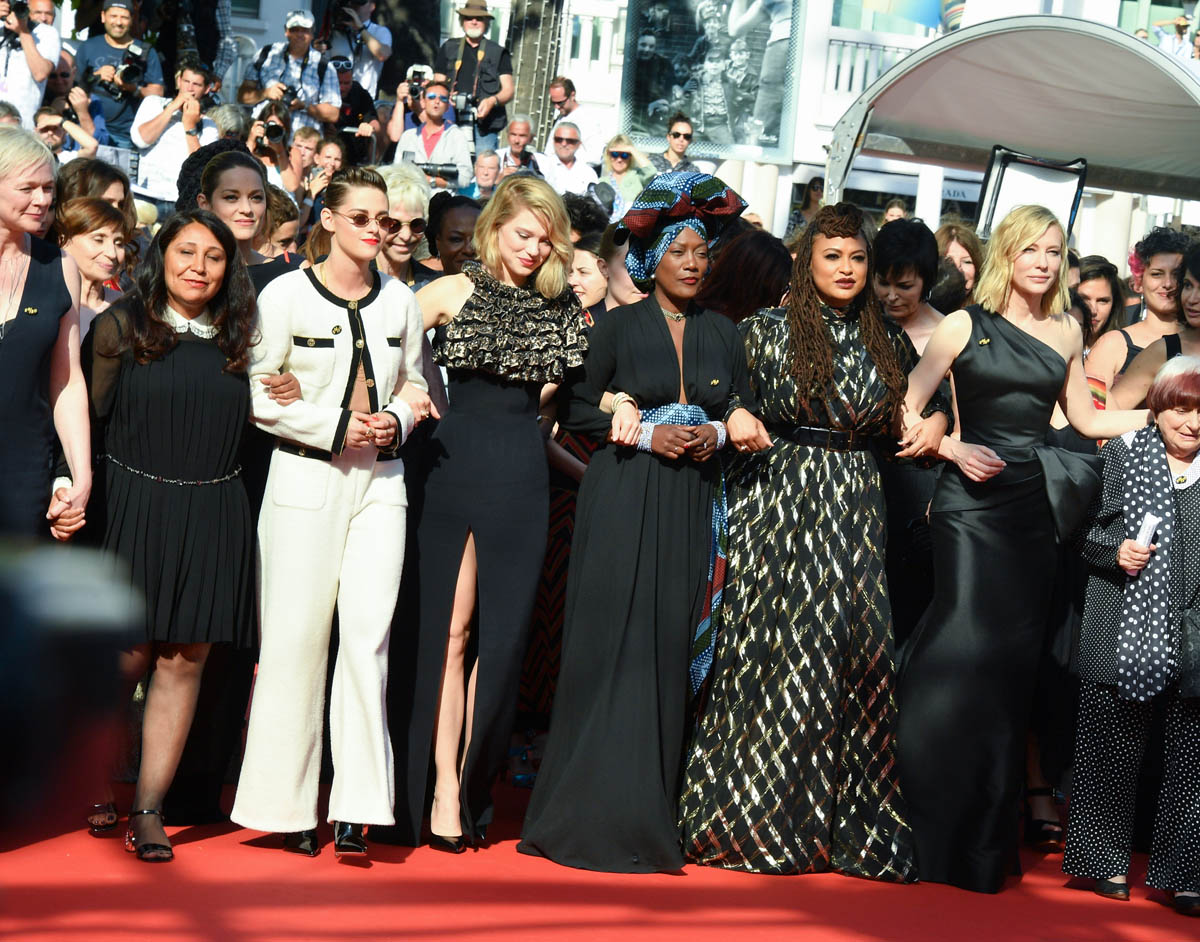

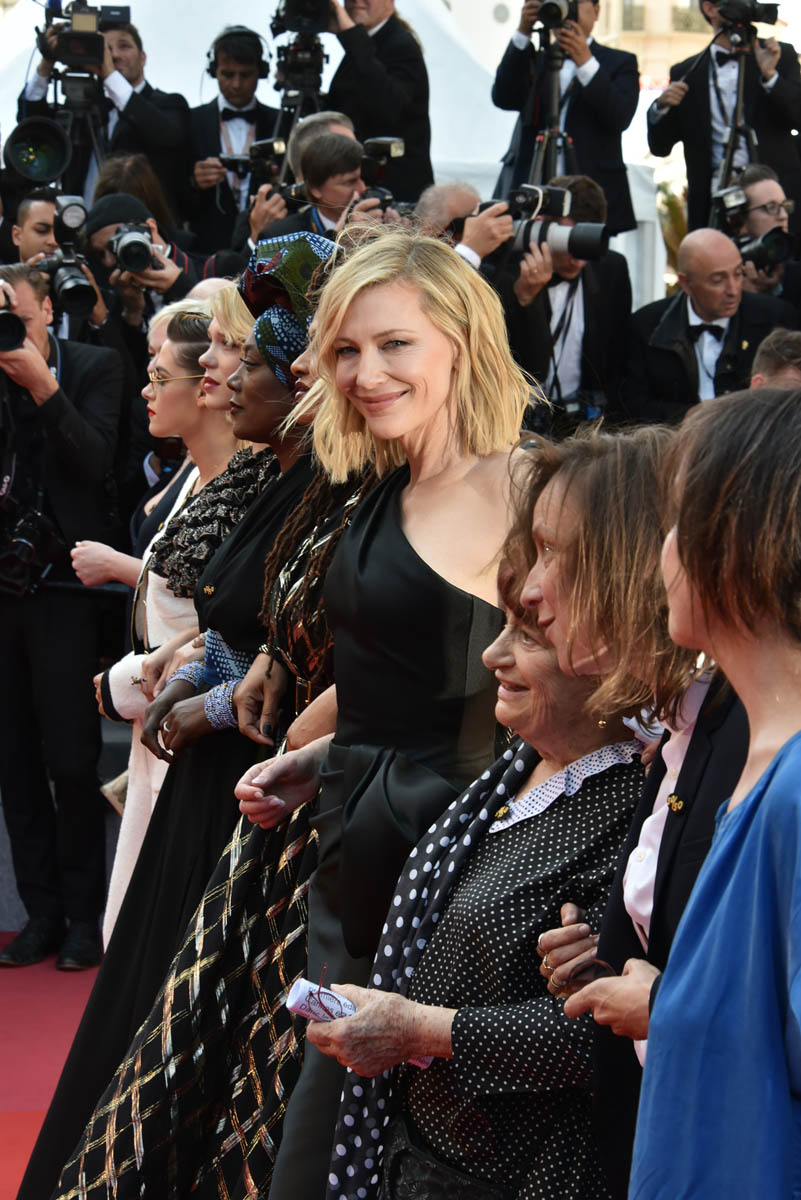

Eva Husson’s Girls in the Sun premiered at Cannes on Saturday, one of only three films in competition directed by a woman. Before the premiere, jury president Cate Blanchett led a march of 82 women up the famous red Palais steps. Significance? In the 71-year history of Cannes, only 82 films directed by women have been included in main competition. Blanchett was joined in the march by fellow jury peers Kristen Stewart, Ava DuVernay, Khadja Nin, and Lea Seydoux, as well as Salma Hayek, Sofia Boutella, Patty Jenkins, and Agnès Varda, recipient of an honorary Palme d’Or (Jane Campion, who was not present, is the only woman in 70 years to win the main competition). Even though festival boss Thierry Frémaux already claimed to “deplore” the Cannes track record and is expected to announce changes to the programming in the wake of #MeToo, it was a significant display, calculated to highlight the shortcomings of a festival which has struggled in recent years with sexist outdated policies.

“Women are not a minority in the world, yet the current state of our industry says otherwise,” Blanchett said, before highlighting the goals of the movement—I refuse to call it a “list of demands” because no one is being held hostage—which include pay equity, equitable and diverse work spaces, and creating an atmosphere that “allows all of us behind and in front of the camera to thrive shoulder to shoulder with our male colleagues.” This event was coordinated with France’s 5050x2020, which shares goals with the 50/50 by 2020 movement that came out of Time’s Up, and of which only talent agency ICM is a public adopter. Blanchett comes across better here than she did in her pre-festival Variety interview, probably because here she doesn’t have to answer for working with problematic people. She’s just acting as a figurehead and leader in her industry, and “we need representational and wage parity” is less personally fraught than pontificating on what to do with a person accused of something serious who won’t ever stand trial for it.

And it’s a bold moment for Cannes, which was one of Harvey Weinstein’s hunting grounds, a place and a festival that came up repeatedly after his sex scandal broke last year. Making this statement on the Croisette is not just about highlighting the shortcomings of the festival’s representation, but reminding everyone that Cannes has been historically unsafe for women (this year, the fest has a harassment hotline). In many ways the atmosphere of the festival, with its floating boat parties, frantic deal-making, and mad scramble for access makes it a perfect playground for a predator, as bad behavior is easier to hide in a bacchanal, and Weinstein loomed large over Cannes, more so even than Sundance.

We’re in the “organizational response” phase of the post-scandal era, and with the exception of ICM, organizational responses have largely been poor. Very little real change has followed in the wake of #MeToo and Time’s Up. A number of high profile people have been kicked out of the club, but some will be back (Louis CK, you can count on it), and others only had to stand outside for a minute (WME’s Adam Venit). But for the most part, business goes on as usual. Sure, everyone got a refresher harassment seminar, but just a few days ago I heard about an exec who has been “repeatedly warned” but still bothered an intern so much she quit. And no one has stopped throwing staplers at their assistants. So the harassment hotline, the women’s march, the female-led jury, and the Monday conference to address #MeToo and pertinent festival changes is an organizational response to course-correct the bad, post-Weinstein publicity. So far, Cannes is doing what it does best and putting on a good show, but we’ll have to wait and see what real changes get made.

Source